Random Thoughts About Carmen

Random Thought #1: Novels to Operas.

Three of opera’s greatest heroines began their lives on the printed page. And all of those pages were French!

- Manon Lescaut

Les Mémoires et Aventures d’un Homme de Qualité qui s’est retire du Monde (“The Memoirs and Adventures of a Nobleman who has retired from the World”) by Antoine Prévost d’Éxiles, or just the Abbé Prévost, was published over a number of years, starting in 1728. In the sixth “volume” of his saga, the Man meets a poor younger man who tells him of his infatuation with Manon Lescaut. This allowed Prévost to add a further “volume,” which was soon separated from its novel parentage and published separately. Daniel Auber (1782 – 1871) was the first composer to realize Manon’s operatic potential with an opéra-comique, in 1856. Some twenty years later, in 1884, another Frenchman, Jules Massenet, brought Manon to such vivid life that Auber’s version virtually disappeared; Puccini’s post-Massenet, and very Italian, Manon Lescaut, which premiered in 1893 and was his first great success, comes in a very distant second!

- Violetta Valéry

What a curse to be the son of the author of such successful novels as The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers! Alexandre Dumas, fils (son) published sixteen novels and some two dozen plays, but today he is known – if he is known – only as the author of the autobiographical novel La dame aux camélias (The Lady of the Camellias) which was published in 1848. Emulating the Abbé Prévost, or maybe the more recently-published short story Carmen by Prosper Mérimée, Dumas adopts the literary conceit of the survivor telling the narrator the story of the great love of his life, who has died. What makes the novel so interesting is that this narrator knew the lady in question and, by chance, encounters the man who loved her. So there’s a kind of double-distancing going on: I knew this person, but now I’m hearing her story from a man who loved and lived with her. Probably we would not know much of Dumas fils had he not adapted La dame aux Camélias into a play of the same name which premiered at the Théâtre du Vaudeville in February 1852. Verdi was there, immediately recognized its operatic possibilities, and quickly had the play turned into a libretto. La Traviata, where Marguerite Gautier (Dumas’s name for his real-life mistress, Marie Duplessis) becomes Violetta Valéry, was a fiasco when it was first given at La Fenice in Venice, in March 1853; three months later, and after some revisions, it achieved (ironically also in Venice, though not at the Fenice) the success Verdi knew it deserved. Of the various film adaptations of the play (there are some twenty of them, including one made in 1913 with the Divine Sarah Bernhardt, the creator of Sardou’s La Tosca, in the title role) the best is probably Camille, with Greta Garbo as the heroine.

- Carmen

Between the births of Manon Lescaut and Marguerite Gautier came that of Carmen. In 1845 Prosper Mérimée published his story of the Spanish gypsy, in the Revue des Deux Mondes – a monthly magazine which printed articles dealing with cultural, economic, and political matters: a sort of cross between The New Yorker and The Nation. For its first commercial publication in 1847, he added a fourth “chapter,” which is a sort of treatise about Spanish gypsies and unnecessary to the story told in the previous three chapters. The translator of my English version of the story, Nicholas Jotcham, considers it “merely inept” and relegates the chapter to an Appendix. Mérimée follows Prévost by having the story’s narrator tell the reader what he was told by the man who loved the woman whose name became the title of the story.

I’m not a literary critic, so I don’t know how many other novels, French or otherwise, whose subject-matter is a relationship ending in the death of the woman, use this Prévost/Mérimée/Dumas-fils technique of the disinterested narrator (less disinterested in Dumas’s case) telling us what he was told by the man who survived. But isn’t it interesting that the three greatest operatic heroines came from French authors using the same narrative device!

Random Thought #2: Soprano or Mezzo.

Should the role of Carmen be sung by a soprano or a mezzo-soprano? (“Mezzo-soprano,” by the way, means a “half/middle-soprano”: a female singer without the really high notes you’d expect from a “soprano,” but without the really low notes expected from a “contralto.”) In some scores the role of Carmen is assigned to a “mezzo-soprano”; in others to a “soprano.” If you check out my “Listening” list you’ll see that while some sopranos have recorded the role, the majority of singers who won success in the role on stage were/are mezzos. So which is she: mezzo or soprano? “Yes” is the simple, if confusing, answer.

Today we have very definite ideas about the roles which should be sung by a soprano and which by a mezzo-soprano, but that has been a relatively recent evolution. Mozart, for instance, saw no vocal difference between the singer of Cherubino and that of the Countess or Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro: as far as he was concerned all three were sopranos, as were Fiordiligi and Dorabella in Così fan tutte. Today, though, Cherubino and Dorabella are given to what are now called “mezzo-sopranos.”

When Verdi was starting out, there were two categories of female voice: soprano (high) and contralto (low). Sopranos we know well; contraltos, not so. Ewa Podleś is probably the best-known of that vocal-category today, though Kathleen Ferrier and Marian Anderson (both from an earlier generation) are still revered for the richness of their voices, and, of course, their artistry. Neither Ferrier nor Anderson could have sung Bizet’s gypsy; and, as far as I’ve been able to ascertain, Podleś has not sung the role either.

After the original production of Carmen ended after a run of 48 performances (45 in 1875 – more than any other opera at the Opéra Comique that year – plus three in early 1876), Galli-Marié went on to sing the role over the next few years (presumably in French, and presumably with dialogue) in various European theatres, including one in Genoa in 1881 where her slightly over-wrought José managed to wound her cheek. But despite its great success throughout Europe and America, Paris would have nothing to do with the opera. Halévy proposed a revival in 1876, but was turned down by Léon Carvalho who had taken over the company from Camille du Locle. The whole thing needed to be toned-down if the Opéra Comique was to mount a new production, and the greatest toning-down could happen only if Galli-Marié did not repeat her Carmen: apparently even the librettists objected to aspects of her performance.

Random Thought #3: Dialogue or Recitative?

The Opéra Comique, where Carmen was first performed on March 3, 1875, was a theatre which presented musico-dramatic works where the musical numbers were interspersed with dialogue, as opposed to the Paris Opéra, where everything was sung: what would have been “dialogue” at the Opéra Comique would be “recitative” at the Paris Opéra – “recitative” is the kind of sung dialogue you’re used to from operas like Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro and Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. Carmen originally had dialogue.

The history books tell us that, while the original production was a failure, its performance at Vienna’s Hofoper, some six months later, with the dialogue turned into recitative, was the triumph Bizet had hoped for in Paris; and that this recitative-version led to the opera’s world-wide acceptance. Sort of. Vienna did require that everything produced there must be sung, so the original dialogue scenes would have to be musicked as recitative. No-one is credited with the condensation of the original dialogue into recitative-speak (though one article I read opined that Meilhac and Halévy were responsible), but we do know that after Bizet’s sudden death, his friend Ernest Guiraud was commissioned to compose the needed recitatives. A procrastinator by nature – or just plain lazy – it seems that the recitatives were either not completed in time for the Vienna premiere, or that Franz Ritter von Jauner, then the Director of the Hofoper, preferred to use only some of them while keeping dialogue for other scenes. Edgar Istel, in an article published in 1921, writes that he saw Carmen in this form in Vienna in 1899; he must have known the opera from the published piano score (which has only recitative) because he thought the production was some sort of later adaptation. He notes that a revival of the opera in Berlin in 1891 “showed that generally speaking no very clear idea prevailed as to how matters stood [regarding dialogue versus recitative version]. The critics thought…recitatives had been ‘restored,” and found the dialogue ‘ridiculous.’”

In May 1900, Gustav Mahler introduced the recitative-only version to Vienna’s Hofoper, and it’s safe to say that from then on Carmen would always be a completely-sung opera in major opera houses; though from the 1911 recording with Opéra-Comique forces, it’s clear that they, at least, still performed the opera with dialogue. In 1957, England’s Carl Rosa Opera Company (which was started in 1873 with the aim of bringing opera in English to London and the provinces), in an attempt to recreate the Opéra Comique’s premiere – before the composer, the conductor, Guiraud (the recitative-guy) and some unknown “other,” made the various changes which resulted in the all-singing version which became the standard performing version – presented a production based on Bizet’s manuscript score. It’s probable that this manuscript score does not contain the dialogue, but that would have been available in Volume 7 of the collected works of Meilhac and Halévy. If you read “The Writing and Rehearsing of Carmen” chapter, you’ll learn that the manuscript score may not be an accurate document of that first performance.

In 1964, Fritz Oeser published a new edition of the score, based on the original sources; unfortunately, he failed to consider the first published piano-vocal score, which Bizet prepared after the premiere and so presumably reflected the musical cuts made during rehearsals. (Again, more on this in my “The Writing and Reheasing of Carmen” chapter!) But at least he gave us the option of incorporating – or not – the dialogue.

Spoken text can be a problem for many opera singers: they are trained to project their singing voices, but not their speaking voices, into such large auditoriums like New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, or San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House; add to that the fact that the “big houses” might cast a German Carmen opposite a Russian José, with an Italian Micaëla and an American Escamillo, all of them singing hither and yon, and you have to wonder when they could meet on one continent, let alone one city, to sit down and work on the dialogue with a French expert. No wonder many companies use the easier option of a recitative-only production. Some American companies opt for that, or come up with their own version (like the original production at Vienna’s Hofoper in 1875) which mixes some of the original dialogue, in either the original French or in an English translation, with some of the sung recitatives. Utah Opera’s production will be sung in French and will include French dialogue. Supertitles provided!

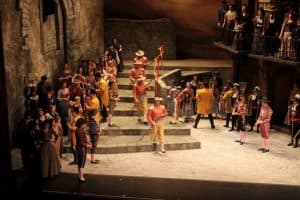

Random Thought #4 Supers in the original production.

In reading Meilhac’s and Halévy’s original Carmen libretto for this series of articles, I was struck by the large number of supers it asks for. Take, for instance, the opening scene. Fifteen soldiers, the libretto tells us, are grouped in front of the guard house; the square is jam-packed with people who come and go, some acknowledging others, while others push past them. Only the soldiers sing, which makes sense, since they are commenting on the comings and goings of the people. It’s possible that the ladies in this opening crowd might have time to change into their cigar-factory-worker costumes, but their escorts could not possibly all be the young men (tenors) who, later in the act, greet those girls. Supers, perhaps? The arrival of the relief guard is preceded by 2 trumpeters and 2 fifers (maybe real players, or, more probably, supers miming the playing); after the relief guard come the kids. (The relief guard may be supers, since the initial singing soldiers could come back during the ladies’ fight, assuming they will sing – but see “The Writing and Rehearsing of Carmen”). The kids are followed by Zuniga and José, and the procession ends with “dragoons with their lances.”

After the changing of the guard everyone exits, leaving Zuniga and José alone to begin their dialogue. At the end of the Act, “les bourgeois” return to watch what will happen when José leads Carmen off to prison. So maybe those ladies in the square at the opening of the act could not become the factory workers since the stage direction says “the women [I’m guessing the factory workers] and the bourgeois re-enter.” Les bourgeois are all supers?

Act 2 takes place in Lilas Pastia’s tavern (inn/dive?). “Two gypsies strum guitars in a corner and two gypsy girls dance centre stage.” Maybe they will sing later.

Act 4, outside the bullring in Seville, gives us such a slew of supers that the heart of Cecil B. DeMille would have been thrilled, except that his 1915 silent movie was based on the original Mérimée novella (no bull-fight) instead of Bizet’s opera, though its heroine was played by Geraldine Farrer, the American soprano who had first sung the role at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1914, with Caruso as her Don José, conducted by Arturo Toscanini – did they sing it in French or in an Italian translation? The square is very busy with people arriving for the bullfight, with various vendors singing their wares. The various chorus folk, including the kids from Act 1, announce the arrival of a group of Toreros (supers) who are followed, disapprovingly, by the cops (supers). Then come the “chulos” (supers) who will taunt the bull; the “banderilleros” (supers) who throw darts into the bull’s neck; and the Picadors (supers) who, as they ride around the ring, hurl lances into the bull to weaken it. (Are they on horseback now? The libretto doesn’t say, but let’s assume they’ll find their mounts inside the arena!)

Finally Escamillo, who will administer the fatal sword-thrust, appears, with Carmen on his arm. But it is not until the Mayor processes slowly across the stage, preceded and followed by his security guards (all supers), and enters the bullring, that all those various toreros, chulos, banderilleros, and picadors can follow him inside – though any audience member must wonder why, since there’s now a backlog of guys waiting to enter the bullring, they didn’t exit into the bullring when they first appeared. Except that’s the stage direction. Reminder: none of these backloggers sing. Which must beg the question: how many guys were in each group of toreros, cops, chulos, banderilleros, picadors and the Mayor’s security detail? A minimum, perhaps, of 4 humans in each group, resulting in at least two dozen male supers. How many companies today could drum up that many supers, even if their costume budget allowed for them? The Opéra Comique must have had, literally, a super super list to call on when a given production demanded extra silent partners.

Based on the original libretto’s requirements, that first production of Carmen may well have been a time when, in the words of the old typewriting exercise (remember typewriters?), all good men were called to come to the aid of the party: said party being the Opéra Comique. It would be interesting to know exactly how many supers were involved in that first production in 1875, though we may never know, since it’s possible they were never paid for their services, and so no record remains. There must have been lots of them over the years. I can only hope that some, at least, emerged from their super experience with a greater understanding of Opera, as I did all those years ago in Ireland.

©Paul Dorgan