Silent Night Program Article by Michael CliveBlessed Are the Peacemakers

“Why do the nations rage,” asks the psalmist David, “and the peoples plot in vain?” War is as old as history — perhaps older — but our modern understanding of its horrors began in 1914, when a regional dispute and political assassination unleashed a war such as the world had never known. World War I killed an estimated 40 million people in an era when the world’s population was one-fifth of today’s. For Europe’s combatant countries, it has been compared to evolution in reverse — taking a generation of the fittest, most combat-ready young men, killing them by the millions, disabling the survivors in body and mind, and devastating their families and their countries.

The violence was often pointless. If weeks of trench warfare succeeded in moving the battle lines forward a few hundred yards, a few more weeks might find them back where they were before. In the week before Christmas of 1914, French, German and British troops called their own small, temporary halt to the bloody tide. In what became known as the Christmas Truce, they stopped shooting and ventured across the trenches to express holiday greetings, exchange food and souvenirs, play some improvised games, and bury their dead. This assertion of humanity in the face of dehumanizing violence was short-lived, occurring in the fifth month of a conflict that was destined to last four more years.

The events of the Christmas Truce helped inspire composer Kevin Puts’ and librettist Mark Campbell’s Pulitzer Prize-winning opera Silent Night and the 2005 film Joyeux Noel on which it is based. But even before the War was over, artists in every medium and genre knew that art history, like world history, would be eclipsed by it — yet that, somehow, art must help us understand the devastation.

Poems and Songs, Pro and Con

Wilfred Owen, one of England’s “World War I Poets,” wrote his “Anthem for Doomed Youth” and other poems while in the trenches. He was killed in action at age 25 in France, on the banks of the Sambre-Oise Canal, a week before the war ended.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Atlanta Opera production of Silent Night

Canadian-born John McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields” after the death of a friend in battle at Ypres, Belgium. McCrae served in the First Canadian Contingent in World War I and as a consulting surgeon to the British Army. He died in France in 1918 at age 45, serving in a war hospital.

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The domestic controversy over America’s entry into World War I is reflected in the anti-war song “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier.” With lyrics by Alfred Bryan and music by Al Piantadosi, sheet music for the song sold more than 650,000 copies in 1915.

I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier

Verse 1

Ten million soldiers to the war have gone,

Who may never return again.

Ten million mothers’ hearts must break

For the ones who died in vain.

Head bowed down in sorrow

In her lonely years,

I heard a mother murmur thru’ her tears:Chorus

I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier,

I brought him up to be my pride and joy.

Who dares to place a musket on his shoulder,

To shoot some other mother’s darling boy?

Let nations arbitrate their future troubles,

It’s time to lay the sword and gun away.

There’d be no war today,

If mothers all would say,

“I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier.”

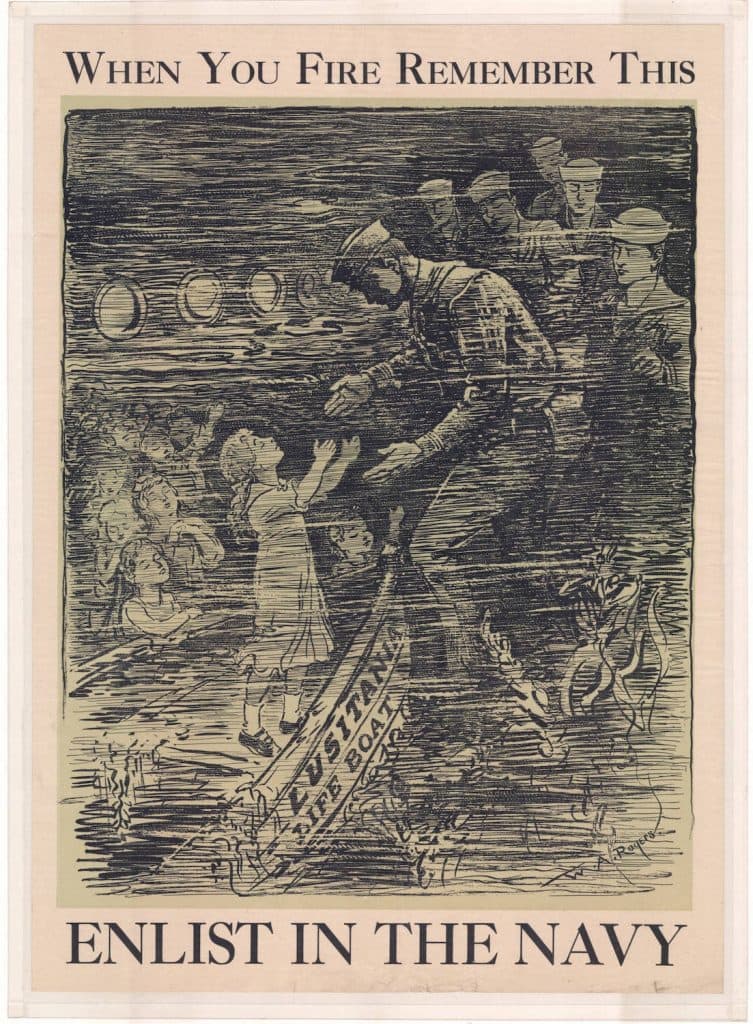

Recruitment Posters

The entry of American “doughboys” into the War was delayed, but decisive. Domestic resistance to America’s involvement began to melt in 1915, when an early German submarine torpedoed the Cunard Lines’ luxury cruise ship RMS Lusitania, which had thousands of civilian passengers aboard, but also military cargo. Among the 1198 civilians who died were 129 Americans. Recruitment posters depicted the tragedy with confrontational, dramatic emotionalism.