The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs Online Learning by Dr. Ross HagenIntroduction to The (R)evolution

Mason Bates’ and Mark Campbell’s 2017 opera The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs has been one of the more successful recent operas (even with the interruption of the Covid pandemic) and pulls together one of the most-performed young American composers and one of the most celebrated librettists of our time. Bates has been composer-in-residence with the Kennedy Center, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the San Francisco Orchestra, among other awards and fellowships, while he and Campbell both received a Grammy award in 2019 for The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs. Campbell’s operas have been produced by the majority of major American opera houses, and he won a Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for the opera Silent Night (produced by Utah Opera in 2020). The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs was jointly commissioned by the Santa Fe Opera, San Francisco Opera, and Seattle Opera (not incidentally, all cities that have been hubs for technology companies). The Grammy-award winning recording is available on all the usual streaming platforms and there is a video production available via The Atlanta Opera, while the San Francisco Opera has a detailed synopsis of the scenes.

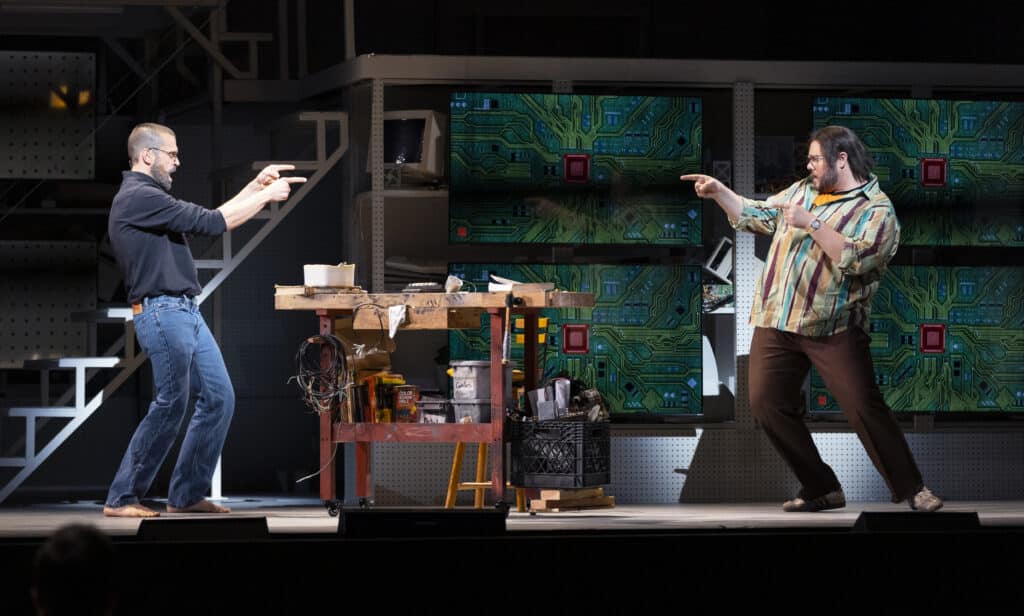

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs unfolds mostly in flashback, as a series of short scenes dramatizing moments in the life of Steve Jobs in semi-chronological order, featuring his Buddhist mentor Kōbun Chino Otogawa, his first girlfriend Chrisann Brennan, his wife Laurene Powell Jobs, and his Apple co-founder Steve “Woz” Wozniak. After a prelude of Steve’s father giving him a workbench when he was a boy, it opens with the announcement of the Apple iPhone in 2007, after which Steve is noticeably winded. His wife Laurene asks him to come home from the office, but he takes a walk around the hills first and is visited by the spirit of Kōbun Chino Otogawa, his former mentor in Zen Buddhism. Kōbun then leads Jobs through a retrospective of his life’s ups and downs before Jobs returns home in the final scenes and is forced by Laurene to accept that he is seriously ill. This structure gives the opera a somewhat cinematic quality, bouncing back and forth across time and space, a perception that is heightened by the ~90 minute runtime. In spite of the non-linear nature of the opera, the fact that it takes place within the memory of its well-known main character and involves actual events also makes it a fairly matter-of-fact biography. The audience also knows where it all leads, even Android users, so the main dramatic unknown is whether Jobs will have any sort of awakening or enlightenment from looking back on his mostly charmed life and the damage he inflicted on people close to him.

Bates’ music also mirrors the episodic and endlessly active nature of much film music; there were moments reminiscent of Alan Silvestri’s engaging and kinetic scores for Robert Zemeckis’ popular comedies in the 1980s and 90s. This sense of nervous activity and constant motion is something of a hallmark for Bates, and in this case it fits well with the restless and ruthless nature of Jobs’ character and the overall setting within the fast-paced technology business. Bates’ electronic techno touches come off well in these scenarios, adding another layer of nervy propulsion to the scenes taking place at Apple’s corporate headquarters in the 1980s. In structuring his music, Bates doesn’t really seem to use clear leitmotifs as such, but rather employs broader sonic palettes and inserts a few key dramatic callbacks. Steve’s memories of bohemian life with Chrisann in the early days feature prominent flashes of nostalgic acoustic guitar, while Kōbun is often underscored with flutes and woodblocks. The libretto itself also relies mostly on the rhythms of everyday speech, so the opera unfolds mostly in the style of Wagnerian recitative with select aria moments.

Within the opera, there are also a couple of consistent lyrical metaphors that repeatedly resurface. In the scenes of their early years in the Jobs family garage, Steve is adamant that their computer hides its mess of wires within a smooth chassis and a minimum of external controls. This begins his “one button” obsession that culminates in the iPod and iPhone, and which recurs several times over the course of the opera. In later scenes it becomes obvious that Steve applies similar logic to himself and his interactions with other people. He hides the mess of “wires” within himself and avoids self-reflection; as with his computers, nobody should be able to open it up and mess with the insides. (Incidentally, this was once one of Apple’s major weaknesses as opposed to Windows machines – it was easy to install upgraded components and replace broken parts in a PC desktop computer, or even build your own custom machine from scratch. It’s also hard not to think of Apple’s more recent history of denying owners the right to repair their devices.) Steve also resents the way others entangle him in their problems, as opposed to the sleek, uncomplicated, and most importantly unfeeling world of machines, an ironic counterpoint to the many references to connection throughout the opera. His need to refuse any appearance of weakness ultimately also leads him to continually deny his illness until Laurene forces the issue.

The opera’s other throughline is the continual association of technological invention and “maker” culture with music and other forms of artistry. (R)evolution sets this up early on in the scene in which Steve and Chrisann take LSD in the park and he begins to hear various musical instruments, clarinets, flutes, oboes, etc. which enter in the score along with some computerized tinkling (Steve is on acid, after all). Steve then realizes that the field is playing Bach. Bach is an apt choice, as there’s a certain cool detachment to his music (at least as it’s performed nowadays) that fits with Steve’s character, as opposed to the emotionality of Beethoven or Tchaikovsky. Further, Bach’s penchant for fugues and musical puzzles makes him a good figure for associating music with mathematics. This explicitly musical association returns when Steve is talking to Woz about their computer’s design (Scene 9: “Music. Bach. Instruments”.), and he declares that the machines will be something we “play” like an instrument. Steve notes that music, while “merely” math, is also a connection to God that elicits deep feelings in listeners, and that their machines can be “the same way,” that they should be able to be played like instruments. Later, when Steve first has Laurene back to his place (Scene 10: “Just Move In?”) she asks if he hears music when he makes things, with references to Ansel Adams and Ella Fitzgerald.

As the opera moves through various periods in Jobs’ life, from idyllic beginnings to more complex and conflicting times, it begins to seem debatable whether or not Bates and Campbell intend Steve to be seen as a reliable narrator. After all, most of the opera explicitly takes place within his memory, which helps explain why moments of intense personal pain in others (particularly Chrisann) are minimized and brushed off, and why his own feelings of betrayal and grudgeholding come to the fore in histrionic fashions. The scene in which Chrisann reveals her pregnancy elicits only a briefly dissonant pause before Steve returns to his work with Woz and the relentless music pushes ahead (although now with a countermelody of cruel indifference). Yet the later scene of Jobs’ removal by the board at Apple is a catastrophe on par with the higher tiers of operatic deaths.

The final stretch of the opera finds Steve witnessing his own funeral, still attempting to control everything over the good-natured reproaches of Kōbun (who we learn died while trying to save his drowning daughter). Steve Wozniak and Chrisann Brennan are there, but the opera gives no indication that there was ever a reconciliation with either of them or with Jobs’ daughter Lisa (in real life, it seems that they all had understandable conflicts, but also maintained lasting and even somewhat amicable relationships with Jobs up to his death). However, the epilogue is mostly in the hands of Laurene, as her character breaks the fourth wall to address the audience directly, noting that in a few minutes everyone is going to once again become absorbed in the phones of Jobs’ creation. Yet Laurene insists that Steve would not want us to be as consumed with our devices as we are, and that he would prefer that we “be here now.” For all the talk of “connection,” the smartphone has also proven to be an alienating and addictive device, not one that we “play” like an instrument but one that more often plays us.

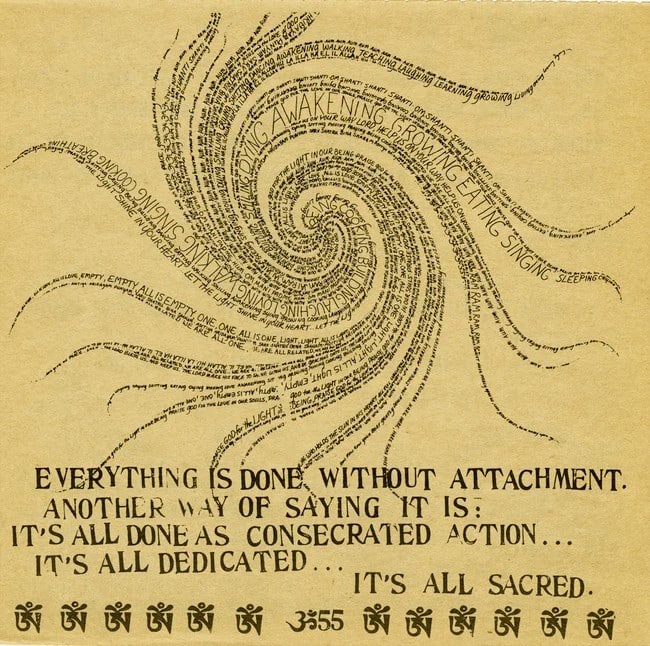

The opera doesn’t really indicate the significance of the line “be here now,” so it’s worth providing some context to help bring the ensō around full circle (couldn’t help it…in my defense Mark Campbell has made the same pun). This line is a reference to one of the more important works of literature to come out of the 1960s counterculture, Ram Dass’s Be Here Now (1971).Dass had been a clinical psychologist at Harvard and UC-Berkeley in the 1960s and was associated with early experiments into the therapeutic effects of LSD and psilocybin along with Timothy Leary and the author Aldous Huxley. Following this period, Dass traveled to India and devoted himself to the Hindu guru Neem Karoli Baba. Be Here Now is both a narrative of his own spiritual journey and something of a guidebook for others seeking similar spiritual fulfillment (with or without the use of psychedelics). Be Here Now and similar works by other spiritual seekers helped to popularize the New Age movement and introduced practices of transcendental meditation and yoga to the wider American public. The Californian “vibe” that cultivated distinctly bohemian and countercultural leanings in the 1960s and 70s also ultimately bled into the DNA of Silicon Valley, and it’s easy to see how the original “phone phreak” anti-establishment mentality became “move fast and break things” in the 2000s. If it’s difficult to locate the influence of Be Here Now in the younger generation of tech companies, it’s perhaps what happens when the upstarts become the establishment.

Yet even for all the opera’s emphasis on Kōbun as a guru, the Steve Jobs of (R)evolution often seems to treat Zen largely as a self-help guide and minimalist design aesthetic rather than a serious spiritual practice. There’s little exploration of the inherent conflict between a spiritual practice that prizes meditation and self-restraint and the acquisitive egocentrism of American tech capitalism. Indeed, Steve is portrayed as being unable to be contained by its constraints because of his forceful personality, and this becomes part of his heroic mystique rather than a failure. Although it is worth considering that being a serious Zen practitioner could also make someone a frustrating coworker, spouse, or parent, particularly if they were already a bit self-absorbed. Somewhat ironically, the device Steve Jobs created with that inspiration seems at cross-purposes with the aims of Zen practice, to say the least. But if you’re into self-reflection and enlightenment, at least there’s an app for that.

Finally, the “(R)evolution” in the title invites multiple meanings. One can think of a “revolution” in the political or technological sense, in which one way of being is replaced by a new order. Alternatively, it invokes its own opposite: revolving and endless return, referenced within the opera by the ensō and its association with the cosmic void and non-being, and perhaps also by its non-linear storyline. The librettist Mark Campbell explicitly related the retrospective nature of the story to the circular ensō and the form of walking meditation called kinhin. It also hints at an inner “evolution” of the Steve Jobs character. The “R” in parentheses also resembles the international trademark symbol ®, to the extent that my word processor wants to autocomplete it every time I write the opera’s title. This subtly (and perhaps unintentionally?) reminds that the “revolution” in the opera is a deeply commercial endeavor – all the stuff about human connection and creativity is backed up by mountains of cash and stock options.