Aìda’s Composer – Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813, in the village of Le Roncole near Bussetto, a small city in Northern Italy. At that time the area was governed by France, so the greatest Italian composer was actually born a French citizen! He was an intelligent child who, at the age of 4, was studying Latin and Italian privately, before enrolling in the village school two years later. Musical talent reared its head early: when he was 8 his parents bought him a spinet which he kept for the rest of his life and is now in the museum of La Scala.

Soon he was assisting the local organist; after he had moved to Bussetto at the age of 10 to continue his education, he returned to Le Roncole as often as he was needed for various church services. Bussetto had an orchestra and also an elementary kind of music school where the teenager thrived, even composing an overture for a touring production of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. A wealthy local merchant, Antonio Barezzi, virtually adopted the young man and, with other Bussettani, collected enough money to send him to study at the Conservatory in Milan.

In the summer of 1832 Verdi duly moved to Milan and auditioned for the Conservatory; he was rejected (“He will turn out to be a mediocrity” was the opinion of one of the adjudicators!) though his age, and the fact that he was a “foreigner” (i.e. from a different province) adversely influenced the panel. He was advised to study privately. He found Vincenzo Lavigna, whose own operas had been successful at La Scala. He had supervised the first performance there of Don Giovanni in 1814, and ended his career there with the premiere of Bellini’s Norma in 1832, the year of Verdi’s arrival in the city. Milanese musical circles soon became aware of a talented conductor and composer, but that promising career was cut short by his forced return to Bussetto, where it was assumed he would take over the position of organist left vacant by the death of his former teacher. Politics in Italy are never simple, and every appointment, even that of church organist and conductor in a small city, is larded with more political fat than any law that might manage to make its way out of Washington! We musicians must rejoice that what seems to us such a minor position could energize the citizens of Bussetto to such an extent that the supporters of each candidate had their separate cafes and restaurants, and that the police were alerted to the possibility of violence between the factions. Apparently there were some kerfuffles.

Piqued by the politicking, Barezzi sent his protégé back to Milan in 1835 where he resumed his studies with Lavigna though not with the intensity his teacher would have liked. Verdi reconnected with a group of amateur singers and instrumentalists, the Filodrammatici, whom he had conducted when last in Milan. They presented oratorios as well as operas ; the director of the group promised to find Verdi a libretto so he could compose an opera for them. The back-and-forth between Bussetto and Milan intervened, and we know nothing about the libretto, except that its author was to have been someone named Tasca.

Finally, in March 1836, Verdi’s appointment in Busetto was approved. His official church duties included composing for the various services; in addition he became conductor of the city orchestra, which presented a varied repertoire of his own compositions and arrangements of popular operas. In April he became engaged to Margherita, the daughter of his mentor Barezzi, and the couple were married in May. Now there are letters to Milan about an opera, virtually complete: Rocester, with a libretto by Antonio Piazza. Since the two month’s vacation from his Bussetto appointment would not give him enough time to prepare the score with the Filodrammatici, Verdi tried to interest the Impressario at Parma, but he was not interested in presenting new works. In 1837 a daughter, Virginia, was born. In 1838 he was back in Milan trying to find a theatre for his opera, and to find a publisher for songs he had written; the songs were published, but the opera languished.

Finally, in March 1836, Verdi’s appointment in Busetto was approved. His official church duties included composing for the various services; in addition he became conductor of the city orchestra, which presented a varied repertoire of his own compositions and arrangements of popular operas. In April he became engaged to Margherita, the daughter of his mentor Barezzi, and the couple were married in May. Now there are letters to Milan about an opera, virtually complete: Rocester, with a libretto by Antonio Piazza. Since the two month’s vacation from his Bussetto appointment would not give him enough time to prepare the score with the Filodrammatici, Verdi tried to interest the Impressario at Parma, but he was not interested in presenting new works. In 1837 a daughter, Virginia, was born. In 1838 he was back in Milan trying to find a theatre for his opera, and to find a publisher for songs he had written; the songs were published, but the opera languished.

In July a son, Icilio Romano, was born, but that joy was overshadowed by the death of Virginia the next month. The young couple decided to quit Bussetto for Milan, where they arrived in February 1839 with the complete score of “my opera.” Every year La Scala presented a concert for the benefit of the Pio Istituto, a charitable organization which gave financial assistance to the widows and children of Milan’s professional musicians; Verdi’s Milanese friends managed to have the opera, which had become Oberto, selected for this performance. The tenor got sick and the performance was cancelled. The composer considered returning to Bussetto for good when he was summoned to the theatre by the impressario, Bartolomeo Merelli. He had overheard the singers discussing the high musical quality of Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio and offered to produce it in the autumn. On November 17, 1839, Verdi’s first opera was presented for the first time. The critics, for the most part, were encouraging; thirteen more performances were given that season; and the publisher Ricordi bought the score. Quite an achievement for the “mediocrity” from Bussetto! The following year the piece was given in Turin, and in 1841 both Naples and Genoa produced the opera.

This would be the place for a footnote, if this were the place for them. It isn’t, so there isn’t! BUT! It is important to bring to your notice Verdi’s pre-Oberto operatic attempts. I’ve mentioned Rocester, and Verdi implies in a biographical sketch that he sent, in 1879, to his publisher Giulio Ricordi that Oberto was merely a touched-up version of Rocester. Perfectly plausible: librettos were often revised with titles and characters renamed. Except that a letter from Verdi in 1871 says that Oberto was a revised version of Antonio Piazza’s Lord Hamilton. What, then, was “my opera,” which Verdi brought with him to Milan in 1839? We will never know. Verdi had a habit of destroying music which, for whatever reason, was cut from the score during rehearsals. Julian Budden (whose 3-volume The Operas of Verdi is, despite its musicological detail, essential reading for anyone interested in the composer and his works for the stage) argues for a revised Rocester.

The success of Oberto prompted Merelli to offer the young composer a contract for three operas at intervals of eight or nine months to be performed either at La Scala or at the Kärntnerthor Theatre in Vienna, of which he was also the Director. Another achievement for the “mediocrity”! For the first of these operas Verdi ignored Merellis’s suggested libretto, and chose, instead, one by Felice Romani, Il Finto Stanislao, which was renamed Un giorno di regno. Romani was the distinguished author of distinguished librettos: La sonnambula, I puritani and Norma for Bellini; Anna Bolena and L’elisir d’amore for Donizetti. The first performance of Un giorno, on September 3, 1840, was a total disaster. In that biographical sketch of 1879 Verdi tells us that in the summer of 1840, when he would have been composing this comic opera, his wife and children died. But his daughter had died in 1838 in Bussetto, while Icilio died during rehearsals for Oberto. What is true is that in June of 1840 Margherita died. Verdi returned to Bussetto with his father-in-law and wrote to Merelli asking to be released from his contract. Merelli refused. Undoubtedly it would be difficult to write any opera, let alone a comic one, after the death of a spouse; but Romani’s libretto was problematic: comic opera was in the midst of a transition, and the inexperienced Verdi was not yet the composer to bridge the stylistic gap. Ironically, five years later the opera, renamed Il finto Stanislao, was a huge success in Venice, and, in 1859, in Naples.

The fiasco didn’t faze Merelli: he simply revived Oberto and sent the composer a libretto for the second of the contracted operas. Verdi’s memory in 1879 is not quite accurate here, either: well, let’s say it’s the accurate account of a man who wants to give posterity his own version of his life! Verdi refused to set Il Proscritto, the libretto sent to him; so Merelli gave it to Otto Nicolai, a German composer who had had a huge success in 1840 with Il Templario, and sent Verdi the libretto Nicolai had refused. His wife’s death, combined with the failure of his second opera, made Verdi seriously consider returning to Bussetto to be a small-time organist/conductor/composer; he threw the libretto aside, but something kept pulling him back to Nabucodonosor. The score was ready by autumn of 1841, but now Merelli was reluctant to put it on. There are accounts of conflicts and rows through the autumn which eventually were resolved and the opera had its premiere on March 9, 1842. It was a complete triumph. Audiences and critics went wild and there were over seventy performances at La Scala that year alone; other Italian theatres produced it and Donizetti conducted it in Vienna the following year.

The fiasco didn’t faze Merelli: he simply revived Oberto and sent the composer a libretto for the second of the contracted operas. Verdi’s memory in 1879 is not quite accurate here, either: well, let’s say it’s the accurate account of a man who wants to give posterity his own version of his life! Verdi refused to set Il Proscritto, the libretto sent to him; so Merelli gave it to Otto Nicolai, a German composer who had had a huge success in 1840 with Il Templario, and sent Verdi the libretto Nicolai had refused. His wife’s death, combined with the failure of his second opera, made Verdi seriously consider returning to Bussetto to be a small-time organist/conductor/composer; he threw the libretto aside, but something kept pulling him back to Nabucodonosor. The score was ready by autumn of 1841, but now Merelli was reluctant to put it on. There are accounts of conflicts and rows through the autumn which eventually were resolved and the opera had its premiere on March 9, 1842. It was a complete triumph. Audiences and critics went wild and there were over seventy performances at La Scala that year alone; other Italian theatres produced it and Donizetti conducted it in Vienna the following year.

I Lombardi alla prima crociata, first performed at La Scala on February 11, 1843, the third of Merelli’s commissioned operas, was, like Nabucco, a huge success with the audience. This time, though, the critics took a somewhat superior attitude, as if to make it clear that, while they could be fooled once by Nabucco, they were not about to be fooled a second time. Audiences loved seeing Italians, or, indeed, any “nation” united against a common enemy, especially if they sang a unison prayer for victory. The prototype had been the chorus of Hebrew Slaves, Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate, which was regularly encored whenever Nabucco was performed. These years marked the beginnings of the Risorgimento, a movement whose aim was to rid Italy of the various foreign “oppressors” who ruled various chunks of Italy and to unite the country under an Italian king: Victor Emmanuel. Verdi, writing operas dealing with peoples struggling to achieve independence from foreign rule, and writing unison choruses with catchy tunes praising freedom from the oppressor, was co-opted by the movement; and we shouldn’t dismiss the notion that Verdi chose those plots, knowing full-well that they would be crowd-pleasers! “Viva Verdi!” was a common graffiti. “Verdi” was an acronym for Vittore Emanuele, re d’Italia (Victor Emmanuel, king of Italy). What young composer would object to that kind of “product placement”? Politics and Verdi seemed destined for each other!

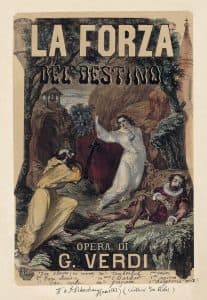

Ernani Venice. March 9, 1844.

I due Foscari Rome. November 3, 1844.

Giovanna d’Arco Milan. February 15, 1845.

Alzira Naples. August 12, 1845.

Attila Venice. March 17, 1846.

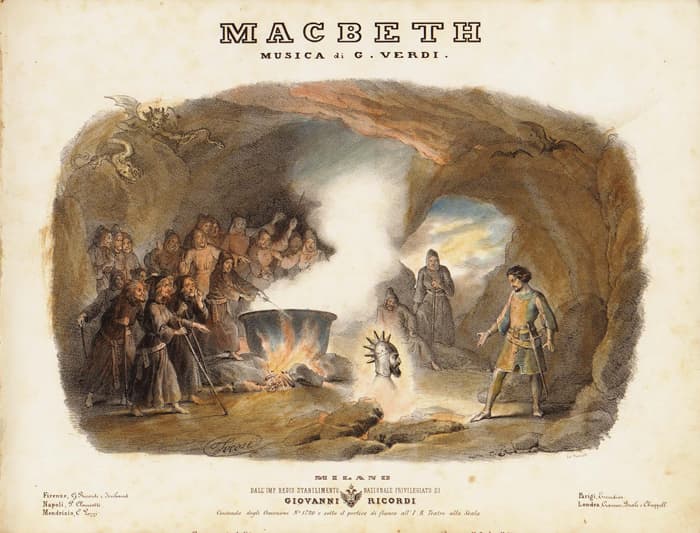

Macbeth Florence. March 14, 1847.*

I Masnadieri London. July 22, 1847.

Jérusalem Paris. November 26, 1847. **

Il Corsaro Trieste. October 25, 1848.

La battaglia di Legnano Rome. January 27, 1849.

Luisa Miller Naples. December 8, 1849.

Stiffelio Trieste. November 16, 1850. ***

Rigoletto Venice. March 11, 1851.

Il Trovatore Rome. January 19, 1853.

La Traviata Venice. March 6, 1853.

*Macbeth was quite extraordinary in many ways for its time. While it wasn’t the only opera without the usual soprano-tenor love-interest, it packed a more powerful emotional punch than its predecessors, and was far more advanced, musically, than its contemporaries. Verdi was very aware of this and there are reports of his incessant demands to rehearse his protagonists! Macbeth’s “dagger” monologue; his duet with Lady; the ensemble after the discovery of Duncan’s murder; Banquo’s apparition at Macbeth’s banquet; all show a composer sure of what he wanted and sure of how to achieve it. The scene of the apparitions in Act 3 must have astonished with its weird sounds. And of course there is the magnificent Sleepwalking Scene for Lady – one of the greatest mad scenes ever composed! Alongside these great moments are laughable ones, usually when the chorus of sorority-like witches is singing and dancing and casting spells and generally having a ball with their newts’ eyes and frogs’ toes! The version we usually hear today is the revision made for Paris in 1865. By then Verdi had a more refined ear for orchestral coloring, so many details of scoring were touched up; Lady’s second act aria, stylistically old-fashioned in 1865, was replaced with something far more sophisticated, as was the chorus of Scottish exiles in Act 4. Despite these changes, much of the 1847 score was untouched.

This is the first of three Shakespeare operas by Verdi: the other two are his final masterpeices, Otello and Falstaff. Verdi often proclaimed his love for Shakespeare, whose plays he continually read and re-read (in various Italian translations). Most musicians rightly revere these three operas, but many of us mourn the Shakespeare opera Verdi never wrote: Re Lear. In 1850 he and Salvatore Cammarano, who had provided Donizetti with many librettos (including Lucia di Lammermoor) discussed the play – not exactly a “discussion”: the composer told the librettist how it should be adapted for the opera house, but it became increasingly clear that Verdi’s ideas were too radical for the older, more traditional librettist, and the subject was dropped, though a draft was written. (Footnote, which isn’t a footnote: in 1850 he received an offer from London to set The Tempest and one, from Italy, for Hamlet; both were turned down because of time constraints, and never again considered.) Lear was suggested as a possible subject for Venice in 1851, but the theatre’s lack of a suitable baritone put it out of consideration. In letters beginning in 1853 he directs Antonio Somma, a well-known poet and fledgling librettist, to look at the play; a libretto was finished shortly before the Paris premiere of Les vêpres siciliennes in 1855. Home from Paris, Verdi had three projects in mind, one of them Lear, most likely for the 1857-8 season in Naples. Again the casting of the three principals (Cordelia, the Fool and Lear – soprano, contralto and baritone) preoccupied the composer. In September the frustrated impressario wrote “Give us King Lear; eventually you may find a better Cordelia, but you won’t find a better baritone, tenor or bass.” Interesting that he doesn’t mention a contralto! But Verdi would not budge about the soprano; he offered a different subject, and the management agreed. Fast forward seven years. The director of the Paris Opéra tried to tempt Verdi back to his theatre by suggesting Lear or Cleopatra (not Shakespeare’s unwitherable temptress!). Verdi replied that Lear would offer none of the visual splendor Parisian audiences expected; besides, “it’s almost impossible to find a Cordelia.” And that, for Re Lear, was that.

** The Académie Royale (or Impériale – depending on France’s ruler du jour) de Musique in Paris could not be ignored by an opera composer. Paris was the musical capital of Europe and its principal opera house (known simply as the Opéra) was the center of that capital, so to receive a commission from the Opéra meant that a composer had “arrived.” Rossini had triumphed there, as had Donizetti and now Verdi was asked to follow in their footsteps. With a mere four months before the scheduled premiere Verdi literally followed Rossini’s footsteps: he decided to take an earlier opera and Frenchify it. There would, of course, be a new plot which would require new numbers, but it was certainly a lot less time-consuming than starting from scratch. Thus I Lombardi became Jérusalem, which was first given November 26, 1847. Opéra audiences were more sophisticated than their Italian counterparts; they preferred, for instance, more continuous music, with the various numbers linked by orchestral commentary, rather than the stand-alone ones the Italians loved because they could applaud the singer. They also expected a more interesting orchestral accompaniment. The required ballet occurs, as required, in Act 3 and is probably the worst part of the score. Neither the French score nor its Italian version, Gerusalemme, were particularly successful. The opera is, however, an important step in Verdi’s development as a composer for it introduced him to a better musical world than was available to him in Italy, even at La Scala. French operas at the time were far more interestingly put together than the Italian variety: plots were carefully constructed; there was a longer rehearsal period, allowing for more detailed work, musically and dramatically; there were opportunities for huge choral scenes; and the larger, and more able, orchestra allowed for greater variety of textures.

*** However much Verdi may have believed in the musical worth of Stiffelio in 1850, Aroldo did no favor to the earlier score. Music written to express the emotions of an Austrian protestant minister married to an adulterous wife could never be successfully grafted on to a plot concerning a thirteenth-century Saxon knight. Despite the musical improvements, and there were many, for Verdi gained in musical polish with each score, the Saxon in 1857 fared no better than had the Austrian minister!

Why Verdi selected a 15-year-old French libretto that had already been set three times is anyone’s guess. And, since it was destined for Rome, why a subject that showed the on-stage assassination of a legitimate king? Naturally there were all sorts of problems with the Roman censors, but Un ballo in maschera is a stunning work. Musically it’s as if Verdi, in 1859, needed to pause for a moment to consolidate his achievements while still managing to move forward. Riccardo may well be one of his most complete heroes before Otello; from France, by way of Mozart, comes the page Oscar – a soprano playing a boy, who contrasts brilliantly with the darker soprano of Amelia, and with the subterranean sounds of the fortune-telling Ulrica. Humor, which we don’t usually associate with Verdi, is present, even if it is horribly ironic.

After Nabucco, its composer and Prima Donna never lost contact with each other, though each pursued their rising and falling stars. In 1847 Giuseppina Strepponi had established herself in Paris as a teacher of voice to young ladies. Verdi visited her there on his way to London. After I Masnadieri he decided to stay in Paris: after all, he did have to convert I Lombardi to Jérusalem, and Giuseppina offered lots of practical advice in his dealings with the Opéra. Then all those revolutions blew up throughout Europe in 1848 – even Paris was not immune, and the couple moved out of the city. Biographers don’t know when she became his mistress but are fairly sure that in 1849 she moved into Verdi’s house, the Palazzo Cavalli, in Bussetto. The local citizenry pried and sniffed to discover something about the woman who lived there in virtual seclusion: few people were invited to the house and those who were saw only Verdi. Some may have known about her checkered past: a brother-in-law accused Verdi of bringing a prostitute to live with him. The move to his farm at Sant’Agata in 1851 only substituted one kind of isolation for another, but they each must have felt a certain measure of freedom, living miles away from the prying and sniffing Bussettani! The one unanswered question – was the composer married to this woman? – was finally answered on August 19, 1859, when, in the village of Collange-sous-Salève, near Geneva, with the coachman and the bell-ringer as witnesses, the couple were married.

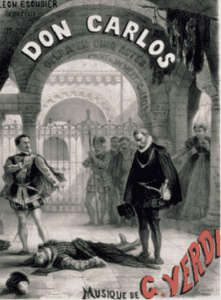

In 1865 a friend from Paris arrived at Sant’Agata with a libretto, Cleopatra, and the scenario of an adaptation of Friedrich Schiller’s play Don Carlos; he had been sent by Emile Perrin, the director of the Paris Opéra, to lure Verdi back to his theatre. Schiller’s play had been considered and set aside about a decade earlier. Thankfully so. For only now was Verdi equipped to tackle this vast drama of politics, religion, love and duty set in 16th-century Spain. As usual at the Opéra, there were all sorts of problems during rehearsals. For one thing, they dragged on too long for Verdi’s taste. Changes were made and then re-made. The dress-rehearsal, when it finally happened, lasted about five hours, albeit with four long intermissions. Further cuts. On March 11, 1867, Don Carlos opened to a tepid reception. Verdi left after the opening; over the course of its run of forty-three performances additional cuts were made (without the composer’s knowledge).

In January 1867, in the midst of rehearsals for Don Carlos, Verdi’s father died. It had not been an easy relationship; in 1851 the son had gone so far as to have a legal document drawn up effectively divorcing his parents. In July his father-in-law, Antonio Barezzi, died after a long illness: “I owe him everything, everything, everything.” In December Francesco Maria Piave, the author of nine librettos for Verdi, including Ernani, Rigoletto and La Traviata, was paralysed by a stroke. Verdi immediately sent money to the family and arranged with Ricordi to publish an album of music to be sold for Piave’s benefit. In November 1868, the great Rossini died in Paris. Verdi suggested to his publisher that Italian composers write a Requiem Mass which would be performed once only in Bologna, the city where Rossini grew up, on the first anniversary of his death. A committee was set up to select the composers and assign them the various sections of the Mass. Eventually this was done, but the commemorative Mass was scuppered by political and religious intrigue in Bologna (where have we seen that combination before in Verdi’s life?). It was performed for the first time in Stuttgart in 1988!! Verdi’s contribution was the final movement, Libera me, which he later used in his Manzoni Requiem.

I promessi sposi , first published in 1827, is regarded as the greatest Italian novel of the 19th century; its author, Alessandro Manzoni, was as much a hero to those fighting for the unification of Italy as was Verdi. The composer greatly admired the author and, when he died, in 1873, Verdi determined to honor him in the only way he could: he composed a Requiem Mass. The first performance took place in the church of San Marco in Milan on the first anniversary of Manzoni’s death; three days later it was given a series of performances at La Scala. A tour of other European cities was arranged and the work was well-received, with a few exceptions. The Wagners, naturally enough, hated it; Hans von Bülow (Frau Wagner’s first husband) dismissed it in a German review, and was himself dismissed by no less than Johannes Brahms, who said that any fool looking at the score would see that the composer was a genius.

To all intents and purposes, Verdi was now retired. He still kept up with the opera world, particularly where his own operas were involved, usually complaining that it was all a mess. He still kept up with Italian politics, usually complaining that they, too, were all a mess! His domestic life was certainly a mess. Financial matters seemed to become very important to him, and friendships that had survived over the years were abandoned because of a debt. In 1879 he wrote two short choral prayers. Around this time Giulio, the new head of the Ricordi firm, at dinner with Verdi and other friends brought the conversation around to Shakespeare and casually mentioned Othello. “I saw Verdi look sharply at me, with suspicion but with interest.” Giulio carefully nurtured that interest over the next years until, on February 5, 1887, Otello was rapturously received by the audience at La Scala. The immediate wonder of the score is that it was ever written: one’s late-70’s is not normally considered to be the age to embark on a musical setting of one of the most harrowing and volatile of all tragedies. Having acknowledged that wonder, it is then possible to examine all the other wonders. A dear friend of mine, who recently retired from conducting at the tender age of 95, holds that Otello is the Bible of Italian Opera. It certainly sums up Verdi’s career, and, indeed, all the operatic progress made in the 19th-century.

In January 1897 Verdi suffered a stroke, but recovered remarkably well. Giuseppina had been ill all year and, on November 14, she died. Performances, and publication of the Pezzi sacri (the four religious prayers he had composed over the past years) occupied him, as did the construction of the Casa di Riposo, a home for retired musicians he was building in Milan. In December 1900 he went to Milan and was his usual self. On January 21 he suffered a stroke and the area around his hotel was quieted as best it could be: traffic was diverted; local carriages were ordered to move as slowly as possible; trams were forbidden to ring their bells; the hotel was closed to incoming guests. On January 27, Verdi died. Milan came to a standstill, as did the rest of Italy. Verdi’s will was strict in its instructions for a simple burial. But when, a month later, his body and that of his wife, were removed to the Casa di Riposo, the world demonstrated its respect: some 300,000 people lined the route to the Casa; Italian parliamentarians, representatives of various governments, mayors, musicians made up the procession; Arturo Toscanini conducted the huge chorus in Va, pensiero: the unofficial national anthem of Italy – a country that didn’t exist when Verdi composed it almost sixty years previously! If Verdi’s career as a musician, a politician, a man, is that of a “mediocrity”, then all I can say is “Long live mediocrity!”