Rigoletto Online Course by Paul DorganPart 1. Background and History of the Opera

by Paul Dorgan

The success, in 1842, of Nabucodonosar, mercifully known today by its abbreviated title Nabucco, brought Verdi multiple commissions from various Italian theatres which resulted in a period he referred to as his “years in the galleys”, where he was compelled to churn out score after score, with little break between each one. I thought you’d be interested in seeing just what those years were like, and why Verdi considered himself a slave, chained to an oar in some galley. So here is a list of his post-Nabucco operas leading to Rigoletto, and going a couple beyond.

1843, February 11; Teatro alla Scala, Milan. I Lombardi alla prima crociata.

1844, March 9; Teatro La Fenice, Venice. Ernani.

1844, November 3; Teatro Argentina, Rome. I due Foscari.

1845, February 15; Teatro alla Scala, Milan. Giovanna d’Arco.

1845, August 12; Teatro San Carlo, Naples. Alzira.

1846, March 17; Teatro La Fenice, Venice. Attila.

1847, March 14; Teatro della Pergola, Florence. Macbeth.

1847, July 22; Her Majesty’s Theatre, London. I Masnadieri.

1847, November 26; Académie Royale de Musique, Paris. Jérusalem. (A revised I Lombardi)

1848, October 25; Teatro Grande, Trieste. Il Corsaro.

1849, January 27; Teatro Argentina, Rome. La battaglia di Legnano.

1849, December 8; Teatro San Carlo, Naples. Lusia Miller.

1850, November 16; Teatro Grande, Trieste. Stiffelio.

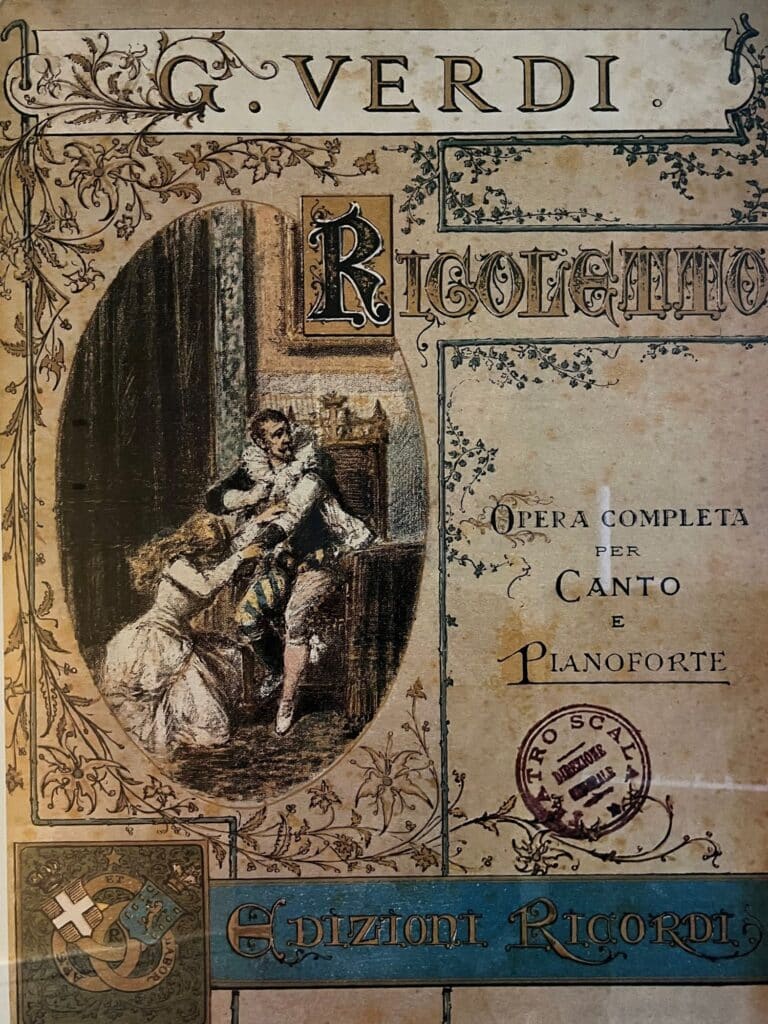

1851, March 11; Teatro la Fenice, Venice. Rigoletto.

1853, January 19; Teatro Apollo, Rome. Il Trovatore.

1853, March 6; Teatro la Fenice, Venice. La Traviata.

That’s some schedule! Bear in mind, too, the difficulties of travel then, and that Verdi was expected to be present at the rehearsals.

Verdi’s first encounter with Victor Hugo was a triumph in Venice in 1844. Hernani, from which the libretto was taken, was notorious even before its first performance in Paris in 1830; and the rowdy reactions (sometimes near-riotous) of the audience at every performance guaranteed the author’s fame, while publication of the script with his own preface only cemented that fame within France, and, in translation, proved his dramatic skills to non-French readers. Le Roi s’amuse was officially proscribed after its first performance in November 1832, but was soon published with the author’s fiery preface. Francis 1, who ruled France from 1515-1547, is an insatiable seducer of women, encouraged in his hobby by his hunchbacked jester, Triboulet, who hates humanity because it is not deformed. The father of one of the King’s seducees denounces Francis for the insult to his family and, as a father, curses the jester. He is horrified for, unbeknownst to any one, he has a daughter, Blanche, whom he keeps closely guarded at home. However, at church (the only time she is allowed out of the house) she has met a poor student (the disguised Francis). The courtiers learn that the jester has a mistress, abduct her and bring her to the King. Now the father’s curse begins to play out and the jester plots the king’s assassination. Needless to say it backfires horrifically on Triboulet: his daughter is killed while the King goes free.

Verdi first mentions the play as an operatic possibility in a letter in September 1849. It resurfaces in a letter to the librettist Piave shortly after Verdi had agreed, in April 1850, to write an opera to be produced in Venice the following year.

I have in mind a subject that would be one of the greatest creations of the modern theatre if the police would only allow it. Who knows? They allowed Ernani…The subject is grand, immense and there’s a character in it who is one of the greatest creations that the theatre of all countries and all times can boast…As soon as you get this letter…run about the city and find someone of influence to get us permission to do Le Roi s’amuse.

A few days later, also to Piave, he waxed further lyrical about both the play and the main character, Triboulet: “a creation worthy of Shakespeare!!…it’s a subject that can’t fail” Should Hugo’s original title be forbidden the opera is to be called La Maledizione di Saint-Vallier (The Curse of Saint-Vallier -which, frankly, sounds like the title of a cheap horror flick!) Interesting that, at this point, Verdi is thinking of the characters as French. And if the baritone Varesi – the original Macbeth – were contracted for the season, so much the better.

Verdi summoned Piave to Busetto to work on the libretto. In August 1850 Piave sent the scenario to La Fenice: “I have been verbally assured that no difficulty will arise over permission to perform it.” But Verdi was not completely satisfied about this “permission” and, in a letter to the impressario, expressed serious doubts, should the subject be forbidden, about his ability to fulfill his contract. What he says is quite fascinating about his method of composition. “I was assured…that there was no obstacle to this subject, and…I got down to studying and thinking deeply about it, and the basic conception, the musical colouring were worked out in my mind. I can say that the main work, and the most difficult, was done. If I should now be obliged to take up another subject, there would not be time to make such a study, and I could not write an opera with which my conscience would be content…It is essential that you should find ways…to obtain permission for Le Roi s’amuse…” Verdi was assured that there would be “no obstacles.”

November brought a request for the libretto. The Imperial Central Directorate for Public Order had heard that Hugo’s play had not been well-received in Paris and Germany “because of the licentiousness with which it is replete.” The libretto was duly sent, but by the end of the month there had been no response, which worried Verdi: time was running out. In early December the ICDFPO ruled that “…the subject has been absolutely forbidden, it is even prohibited to propose any amendments whatever.” The ruling regretted that composer and librettist “have not been able to choose some other theme…than one of such repellent immorality and obscene triviality…” Verdi was devastated, blamed Piave, and said there was no chance of a brand-new opera at this late date, but would Stiffelio, new to Venice, do?

Meanwhile Piave revised his libretto and managed to have it approved. Verdi was not impressed: “it lacks character…and the dramatic situations have lost all their effect.” Names and location had been changed, but surely an “absolute ruler” was required. There was a problem with the curse; there was a problem that the Duke was not a serial-seducer; there was a problem with the elimination of the sack; and what was the problem with Triboulet being ugly and deformed? For Verdi that was “the beautiful thing. I chose this subject precisely for these qualities…and if they are taken away, I can no longer write music for it…out of a drama which was powerful and original has been made something utterly commonplace and ineffective…”

This obviously stung and before Christmas the impressario replied that the Duke of Wherever “can be a libertine and the absolute ruler…The jester can be deformed…There will be no objection to the sack…” It was arranged that Piave and the impressario’s secretary would come to Busetto to work on the revisions: the action would be moved to “one of the petty absolute princes of the Italian states”; the names will be changed, but the “character types” will not; the “key” scene will be eliminated (Blanche, abducted to the Palace, locks herself in what turns out to be the King’s bedroom – he produces his own key and enters the room – surprisingly erotic symbolism for the early nineteenth-century!); the duke will be invited to the inn of “Magellona”; the sack is to be left to Verdi’s discretion. A fortnight later the latest libretto was ready to be sent to the ISDFPO. But Verdi still needed changes from Piave and even by the end of January 1851 there was no guarantee that the opera would be approved.

Official approval was finally granted on January 25: names had to be changed, to protect the guilty, but no re-writes were demanded. Piave claimed to have become quite an athlete, so much running around from office to office had he been required to do!

On February 19 Verdi arrived in Venice to supervise the final three weeks of rehearsal. The audience loved the opera, but critics were confused. One went into detail about the novelty of the score and so it could not be adequately judged by one performance. Another one (English!) thought it “puerile and ridiculous, full of vulgarity…barren of ideas”. Julian Budden, in his discussion of the opera, calls it “one of the most remarkable artistic syntheses in Italian opera.” I’ll talk about that in the MUSIC page.