Sweeney ToddFrom origins to the opera stage

Nineteenth century industrial London was the largest city in the world, and the capital of the largest empire in the world yet housed some of the most desperately poor slums within its borders. While the economic landscape was in flux, literacy was on the rise, the printing process was improving, and the concept of reading material as entertainment emerged. As the middle and lower classes became ready to read, they needed affordable material to consume.

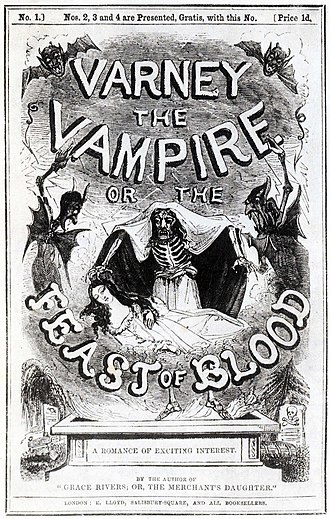

Enter the penny dreadful, a serialized story with a new chapter released every week. Penny dreadfuls were eight to sixteen pages in length, printed on the cheapest possible paper. The cost was, yes, one penny, as opposed to the stories of Charles Dickens and his like, which cost one shilling per installment. At the height of the genre’s popularity, 1830-50, there were over one hundred publishers focusing on this mass-market literature. The cost-consciousness of production led to widespread distribution of these stories, but the cheapness of the material meant that unfortunately few of the original publications have survived to the present day.

Penny dreadful stories told of the seamier side of life-criminals, detectives, murderers or monsters—and were poised for maximum circulation, particularly aimed at young men and boys. One could say these serialized stories were the precursors to the colorful comic books of the twentieth century. Some popular titles were Varney the Vampire, Spring-Heeled Jack, and A String of Pearls, published between 1846-1847, which introduced the character of Sweeney Todd, the “demon barber of Fleet Street.”

There is no absolute historical evidence of the existence of a murderous barber who was supplying meat to a pie shop owner, though word-of-mouth accounts of that era hinted that such a criminal might exist. The basic elements of the story Sondheim eventually tells are all contained in A String of Pearls. In addition to the diabolical partnership of barber and pie shop owner, there are the ingenue and the young romantic hero, and the innocent accuser deemed a madman for his wild stories of cannibalism. A String of Pearls was quickly adapted into a play, even before the final installment of the story was released, and subsequent versions of the story and play were released in England and America over the next decades. By the 1870s, most English-speaking Victorians knew the tale of Sweeney Todd.

British playwright Christopher Bond created his own dramatic retelling of the story in his 1970 play Sweeney Todd. Bond’s version is more sophisticated, adding a back story to Sweeney’s tale, thus giving psychological motivation to his actions. Bond’s Sweeney is sentenced to transportation to Australia by a corrupt judge, who subsequently assaults Sweeney’s beautiful wife, sending her into madness. Upon Sweeney’s return to London, he is determined to exact vengeance on the Judge and his cohorts. Stephen Sondheim saw Bond’s play in 1973 during its run at Theatre Royal Stratford East and immediately saw its potential as a subject for a work of musical theater. Bond’s refined language and plot expansion elevated the story beyond its lurid roots, and Sondheim thought music could only continue that process.

Hal Prince and Sondheim had already collaborated successfully on the musical Company, and continued their partnership with Sweeney Todd. Initially Prince found the subject less than compelling, but when he began to see it as a metaphor for the ravages of the Industrial Revolution, he found his inspiration.

What I did to Chris’ play is more than enhance it. I had a feeling it would be a new animal. The effect it had at Stratford East in London and the effect it had at the Uris Theater in New York are two entirely different effects, even though it’s the same play. It was essentially charming over there because they don’t take Sweeney Todd seriously. Our production was larger in scope. Hal Prince gave it an epic sense, a sense that this was a man of some size instead of just a nut case. The music helps to give it that dimension.

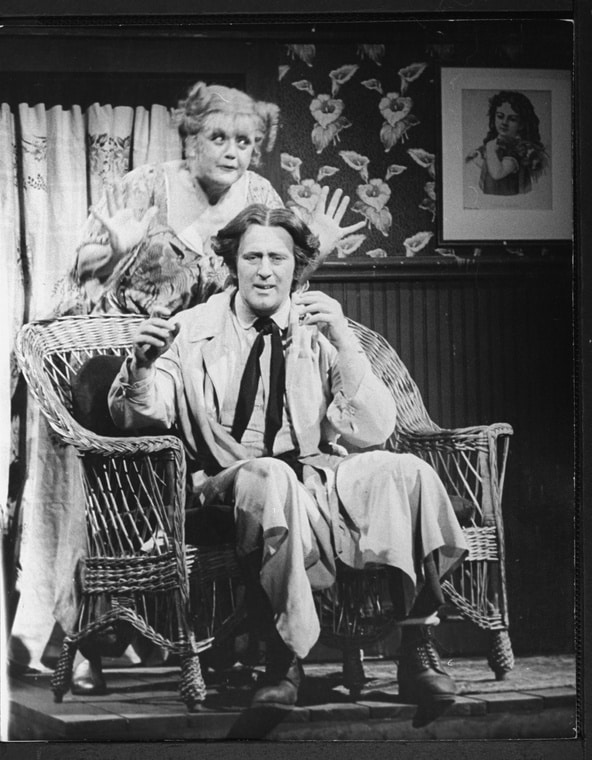

With veteran actors Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury as Todd and Lovett, the musical was a huge success, with the New York Times critic Richard Eder writing (in his somewhat mixed review) “there is more artistic energy, creative personality and plain excitement in ‘Sweeney Todd,’ which opened last night at the enormous Uris Theater and made it seem like a cottage, than in a dozen average musicals.” Sweeney ran for 556 performances, and garnered dozens of awards including Tonys for Best Musical, Best Actress in a Musical and Best Actor in a Musical. Sweeney has been revived three times on Broadway, most recently in 2023 with Josh Groban in the title role.

Sweeney Todd as a theater piece straddles genres—it’s operatic in scope, with eighty percent of the piece sung. Sondheim called it a “dark operetta,” and Eder in his opening night review remarked, “it is in many ways closer to opera than to most musicals.” Supposedly on opening night, influential critic Harold Clurman rushed to Schuyler Chapin, at that time general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, to demand why Chapin had not produced the work. Chapin’s response was “I would have put it on like a shot if I’d had the opportunity. There would have been screams and yells but I wouldn’t have given a damn. Because it is an opera. A modern American opera.” The role of Sweeney is a dream role for any dramatic operatic baritone who has acting chops, and most of the other roles can be cast with singers trained in the more operatic style of singing. Sweeney Todd can be produced with singing actors, as in the film version starring Johnny Depp, with a reduced orchestra of nine players, or with student actors in the “student version,” but a version that utilizes the full vocal, choral, and orchestral resources of an opera house can fully express the drama and horror of this timelessly terrifying cautionary tale of good versus evil.