The Big Story Behind Tosca

by Kathleen Sykes

Theatre is a unique form of entertainment. While a film or television show can be replayed over and over to the same dramatic effect, you only get a few chances to see a piece of theatre before it completely disappears, and no two performances are ever the same.

And while your favorite TV show is confined to the flat-screen device in your living room, one of the things that sets theatre—and more so opera—apart from television is how much the production can expand beyond the edges of the stage. Puccini’s Tosca is a prime example of this.

The Harsh Reality of Tosca

When Puccini set out to write Tosca, he did his research. This was no opera to be based in fairytale or myth as so many of his predecessors had done—he fully embraced verismo, or the “realistic” style of opera characterized by violent plots, naturalistic singing, passionate declamation, and emotionally-charged harmonies and melodies.

His taste for realism didn’t stop there. Puccini did incredibly detailed research into exactly when and where the story would take place (Rome over the course of approximately eighteen hours from the afternoon of June 17, 1800, to dawn on June 18, if you were curious); the exact locations of events; what was going on in the world at the time; and even the pitch of church bells heard in Act I.

An opera like this creates many logistical challenges, from building costumes that are correct for the time period to sourcing an instrument that not only is the same pitch as the aforementioned church bells—but can also fit in a modern orchestra pit! While some opera companies have ventured to do modern interpretations of Tosca (like the one from the Bregenzer Festspiele featured in the Bond film, Quantum of Solace), many people love productions that are faithful to the core of the story.

Fortunately, Utah Opera has an incredible team of artisans, craftspeople, and musicians to bring this classic opera to life the way that Puccini intended.

Setting the Stage

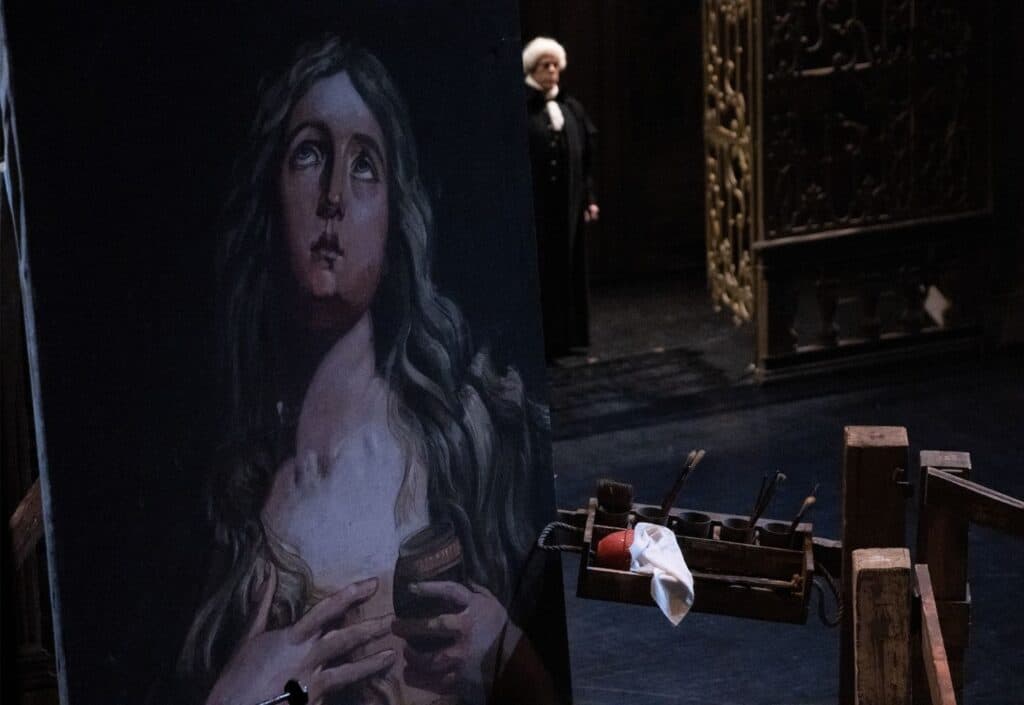

If you had never seen the stage of the Janet Quinney Lawson Capitol Theatre before seeing the Act I set, you would think that the stage was gigantic. The set is a beautifully designed “wing-and-drop” owned by the Seattle Opera and designed by the late Ercole Sormani—a master of this set-building method—to create the illusion of more space.

Each set piece is either a “wing” (where the performers enter the stage) or “drop” (the background), painted with incredible detail and forced perspective to look like iconic locations in Rome: the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle, the Palazzo Farnese, and the parapet of the Castel Sant’Angelo.

If you’re a regular opera-goer, you might notice that you don’t see sets like this very often. Utah Opera Scenic Charge Artist Dusty Terrell says, “I think that the most remarkable thing about the sets is their historical value. These drops are around 70 years old and are painted in a historical style that most painters aren’t often asked to paint in today.”

The set is filled with Easter eggs and exciting details like hidden doors (for torturing political dissidents, of course). For Terrell, however, one of her favorite hidden features is the translucency of the church windows in Act I. She says, “The windows are treated in a way that, when lit from behind, the lighting designer can change the time of day—from bright to night.”

Costuming the Citizens of Rome

With such a specific time and place in mind for this production, our costume shop had its work cut out for it. We would be using the costumes we had in stock to match Stage Director Omer Ben Seadia’s artistic vision. Costume Director Cee-Cee Swalling says, “The idea with this build of Tosca was to use what stock we had and make it into one, cohesive production.”

She adds, “When you are working with costume stock that you’ve owned for a long time, sometimes the look of the production shifts. Depending on what’s being performed and when that opera is set, something might get pulled from one opera and placed in another to fill a gap.” This particular production of Tosca recycled costumes from Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin—set about 30-40 years later—and updated some existing Tosca stock to make it fit a somewhat ominous color palette.

When you think of fashion in Napoleonic Europe and the early 1800s, Jane Austen and Bridgerton often come to mind. But film and television interpretations only offer a glimpse through the lens of fantasy into how people dressed back then. “People have an idea of what the past looked like, but don’t always know what class distinctions looked like or how people dressed for specific occasions,” Swalling explains.

Particular attention to detail went into designing the costumes for the sopranos and altos of the Utah Opera Chorus in Act I. Swalling embraced Puccini’s vision of verismo, and she thought through details like class distinctions and how someone would be dressed to go to church in the daytime in this time period. She explains, “Women often wore caps, bonnets, and long sleeves in the daytime for modesty and to protect them from the sun, and this was a must if you were going to church.”

Puccini’s Haunting Score

There is no denying that Puccini’s score to Tosca is an iconic masterpiece. Utah Symphony Principal Percussionist Keith Carrick says, “Puccini writes absolutely beautiful music, and really excels at creating an imaginary world, a lush musical landscape.” And truly that musical world extends beyond the edges of the stage—one of the most exciting parts of this opera is all of the music that is played off-stage and outside of the orchestra pit.

Michaella Calzaretta, Utah Opera Chorusmaster, also doubles as the Assistant Conductor on a production like this where much of the music is being played out of view of Conductor Stephen White. She says, “I think it’s so exciting to listen for the offstage music, which provides spatial awareness that is paramount to the storytelling. There is so much action that happens outside of what is presented on the stage itself.”

On a typical show night, she is backstage dashing from place to place—with incredible, rehearsed precision—conducting cowbells, chimes, snare drums, the chorus, principal artists, and a real organ like you’d find in a church.

In one of her favorite scenes from this opera, she faces a special challenge. “For this particular scene, the chorus is in a different time signature than the rest of the performers!” she says. “The orchestra plays music that matches what is sung on the stage, but the chorus is completely separate, a cappella, because our music represents action that takes places in an entirely different location in the story.”

Carrick also faced some special challenges preparing for this performance. “Puccini writes for church bells, in the pitches he actually heard, which are very low,” he says about the grand, ringing of the bells in the finale of the first act. “Just imagine how big the actual bells would have to be!”

Anyone who has ever been inside of a real bell tower knows exactly what Carrick is talking about. Church bells are large, loud, and intended to be heard over a large, bustling city—but how do you fit that huge sound in a regular-sized orchestra pit?

He explains, “The challenge is to imitate the bells as best we can while delivering the clear pitch and projection needed for live performance. In this production, we’re using a set of really low-pitch chimes, which required us to make adjustments to our chime rack (which wasn’t tall enough) and provide steps so that we can actually hit the chimes!”

You can’t miss this larger-than-life opera. Get your tickets here and watch it happen live.