Bizet & Opera in 19th-century Paris

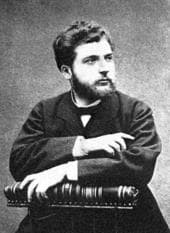

In the early 1860s, Georges Bizet was a potential rising star of the Parisian music world. He had had a successful education at the Conservatoire de Paris, during which he made the acquaintance of Charles Gounod, and in 1857 won the coveted Prix de Rome award. As a part of his award, Bizet was given a five-year grant to compose in Rome but returned to Paris with two years remaining on his grant in order to tend to his ill mother. Once in Paris, he found that his previous successes did little to open doors of the Parisian music scene.

The Pearl Fishers’ initial production was the result a series of extremely fortuitous opportunities for the young Bizet. The two state-sponsored opera houses of Paris at the time, the Opéra de Paris and the Opéra-Comique, performed a repertoire of established operas by composers like Rossini and Meyerbeer and were resistant to new works even by well-known French composers. However, Bizet’s status as a recent Prix de Rome laureate opened the door to the Opéra-Comique as it was obligated to occasionally mount one-act operas by Prix de Rome winners. While Bizet was rehearsing his commission there, the now-lost opera La guzla de l’Emir, the offer to write a full opera for Cormon and Carré’s libretto for The Pearl Fishers came in from Léon Carvalho and the Théâtre-Lyrique. Under Carvalho, the Théâtre Lyrique became the central venue for staging new works by French composers. Carvahlo had been offered a large grant to produce a new full opera by a Prix de Rome winner and in turn offered Bizet the opportunity. Bizet accepted and withdrew La guzla de l’Emir from the Opéra-Comique, and parts of it were repurposed into The Pearl Fishers.

It’s worth noting just how exceptional this stroke of luck was for Bizet. The Parisian opera institutions were by this time practically closed-off to works by new composers. Additionally, the repertoires of the individual opera houses were rigidly defined by genre. The prestigious Opéra de Paris specialized in opulent five-act tragedies lyriques and grand opéra while the Opéra-Comique produced lighter comic operas and the Théâtre-Italien mounted Italian opera exclusively. The grand opéra tradition epitomized by composers like Giacomo Meyerbeer relied extensively on spectacular stagecraft complete with moving sets, electric lighting, ballet sections, and dozens (if not hundreds) of chorus members and extras. For example, Meyerbeer’s 1831 Robert le diable was celebrated as much for a famous ballet sequence featuring the ghosts of dead nuns as it was for its music.

It’s worth noting just how exceptional this stroke of luck was for Bizet. The Parisian opera institutions were by this time practically closed-off to works by new composers. Additionally, the repertoires of the individual opera houses were rigidly defined by genre. The prestigious Opéra de Paris specialized in opulent five-act tragedies lyriques and grand opéra while the Opéra-Comique produced lighter comic operas and the Théâtre-Italien mounted Italian opera exclusively. The grand opéra tradition epitomized by composers like Giacomo Meyerbeer relied extensively on spectacular stagecraft complete with moving sets, electric lighting, ballet sections, and dozens (if not hundreds) of chorus members and extras. For example, Meyerbeer’s 1831 Robert le diable was celebrated as much for a famous ballet sequence featuring the ghosts of dead nuns as it was for its music.

Given the expense of such productions, it is understandable that the management of the Opéra de Paris would reserve their resources for productions that had already been proven successful over the years. It perhaps brings to mind modern blockbuster Hollywood films and Broadway musicals. Neither environment is particularly conducive to innovation simply because of the massive financial interests at stake, so they rely on proven product lines (Spiderman, Transformers, Legos, etc.) or in the case of Broadway they continue long-running shows like the seemingly immortal Phantom of the Opera (1988 – present), revive old successes, or cobble together new shows from music that audiences already know (Mamma Mia!, Rock of Ages, Jersey Boys, etc.).

Parisian opera added the stultifying influences of rigid tradition and hallowed institutions to the mix. Even a well-known composer who enjoyed awards, respect, and veneration would often find that the doors of the Opéra de Paris were closed to him. The hierarchy and divisions between the specialized institutions were such that even composers who had years of successes at the Opéra-Comique found themselves pigeon-holed and never gained entry to the Opéra. It wasn’t until 1959 that Carmen, arguably the most famous French opera of any type, was produced at Paris’s premier opera institution. In such an environment, young and unproven composers had to make do with one-act operas performed during unfavorable time slots to mostly empty houses and hope that some fantastic stroke of luck would change their fortunes. For the opera directors, these small opportunities allowed them to claim that they supported the up-and-comers even as they stacked the deck against them and pretended that these new operas failed solely on their own merits. Carvalho’s venture with the Théâtre Lyrique was an attempt to mitigate these circumstances somewhat.

Even if a composer somehow did manage to win the favor of a theater’s management, he would still have to get a librettist on board, which was in this time period much more easily said than done. The successful operas in mid-century Paris were generally all written by a small group of librettists, and the theaters would often only produce operas with librettos by members of this clique. For the most part, these librettists were inaccessible to unproven composers, if only for the simple fact that they were in such high demand and probably also had little incentive to risk giving their play to a rookie.

Both librettists and composers also had to take into account the fairly rigidly defined operatic genres of the time period, as both theatrical directors and audiences could be quite hostile to works that did not meet their expectations. The genres were defined not only by musical conventions but also by their staging and subject matter. Opéra-comique typically alternated between spoken dialogue and singing, and the musical numbers were typically standard forms featuring clear melodies and simple harmonies without much chromaticism or contrapuntal complexity. Although opéra-comique initially featured light, comedic plots, it eventually incorporated more serious subject matter even as it tended to rein in musical excesses. Grand opéras, as noted above, were typically four or five-act works of massive scope and spectacle, both in terms of staging and music. Over the 19th century, the grand opéra orchestra grew larger and began incorporating new instruments (especially percussion) to achieve novel tone colors and effects. By mid-century, the typical plot of a grand opéra was a serious historical drama filled to the brim with tragedy and pathos.

The Pearl Fishers straddles the divide between grand opéra and opéra-comique, a precarious gambit in this environment. Lacombe argues that The Pearl Fishers was actually a part of an attempt by the Théâtre Lyrique to appropriate grand opéra away from its established circuit. (Lacombe 241) Like a grand opéra, The Pearl Fishers is sung throughout without spoken dialogue (a last minute change, apparently) and contains some elements of dance. However, it lacks the expansive five-act structure, extended ballet divertissements, massive crowd scenes, and focus on historical plots that defined the grand opéra genre. In its scope and staging, it is much more akin to opéra-comique, yet it also goes beyond the reliance on dance rhythms and simplistic orchestration that was a hallmark of that style. It’s certainly possible that The Pearl Fishers’ disappearance from the stage for more than 30 years following its initial run was due at least in part to the fact that it didn’t meet the demands of an audience grown accustomed to having its expectations met with precision.

An aspiring French opera composer like Bizet would also have had little recourse but to attempt to break into this world, as Paris held a veritable monopoly on operatic production within the country. Indeed, the capital city was the sole hub for fashion, prestige, and tradition in France, and it jealously guarded its prominence. For composers, this created a rather unique bind. A composer in Italy could shop his music to Milan, Florence, or Venice if Rome wasn’t interested, and German composers could find good opportunities in Vienna, Prague, Dresden, or Weimar. From a historical standpoint, this situation reflects the fact that both Italy and Germany had long been made up of smaller independent city-states that competed with each other for wealth, power, and artistic prestige. France, on the other hand, had maintained a relatively stable hold on its current territory (save for a few periods of expansion and conquest) since the 11th century, with Paris as its capital and center of artistic activity and learning. This history ensured that not only would Paris draw all things fashionable and artistic to itself, but also that it would zealously enforce its artistic conventions, institutional hierarchies, and standards for decorum and deference. Much of the criticism of Bizet following the premiere of The Pearl Fishers focused less on the opera itself and more on the fact that he appeared for a curtain call at the end, which was interpreted as a brash and arrogant violation of the customary humility expected of composers.

© Ross Hagen