Article by Michael CliveOh, Marie!

by Michael Clive

Girls who grow up to find love and success in a man’s world are no strangers to American audiences. In Irving Berlin’s Annie Get Your Gun, for example, Annie Oakley informs rival sharpshooter Frank Butler that “anything you can do, I can do better.” Not unlike Elly May Clampett, who could out-rassle her strapping cousin Jethro Bodine on television’s classic The Beverly Hillbillies. But while the captivating heroine of The Daughter of the Regiment fits this mold, she and her aristocratic relations are very French — and not the folks we thought we knew.

For Gaetano Donizetti, who composed this tuneful romp, Marie’s French-ness was a high-stakes challenge. Though he had already composed sensationally popular comic operas, La fille du régiment was his first composed expressly in the French style for French audiences. They were already familiar with his Italian-language comedies, but expected something different this time. And some disgruntled French opera composers were openly hoping for its failure.

Born in the mountain town of Bergamo in 1797, Gaetano Donizetti made his mark in Italian opera at a time when the rules of the game were strict for both composers and librettists. Solo arias and ensembles, which required beautiful melodies and opportunities for vocal display, had to be arrayed in the approved structure. In comic operas, the characters were variations on archetypes handed down through generations of commedia dell’arte tradition. More serious operas required a high moral purpose and characters of noble birth or character.

Though he composed by these rules (and at amazing speed), Donizetti imbued them with a freshness and sensitivity to character that astonished librettists and audiences alike. Even so, Marie, the heroine of The Daughter of the Regiment, is not someone whom Italian operagoers of the day would have recognized. By 1838 success had brought Donizetti to Paris, Europe’s undisputed cultural capitol at that time, to revise his opera Poliuto as Les martyrs for the Paris Opéra. A delay in the production gave Donizetti a chance to squeeze in something new—something that became his first comic opera in the French style, La fille du régiment. His Italian-style comedy The Elixir of Love had aroused an adoring public at the Parisian Théâtre-Italien, but nothing suggests that Donizetti harbored similar ambitions for his “Daughter,” who seemed rather more casually conceived and experimental. “I have written, orchestrated, and delivered a little opera for the Opéra-Comique which will be given in a month or 40 days,” he wrote of it to a friend, seemingly with no expectation that it would conquer the world’s opera houses so quickly.

Then again, Donizetti’s description may have concealed a bit of coyness. He knew that the speed and skill with which he composed, often rewriting his libretto in the process, could be a sore point with colleagues—and that the tidal wave of his success in Paris was greeted with defensiveness in some quarters of the French musical establishment. Eminences including Hector Berlioz, whose writing as a music critic was often reserved and statesmanlike, were provoked. “Two major scores for the [Paris] Opéra…two others at the Renaissance…two at the Opéra-Comique, Le Fille du régiment and another whose title is still unknown, and yet another for the Théâtre-Italien, will have been written or transcribed in one year by the same composer,” Berlioz wrote in the Journal des débats. “M. Donizetti seems to treat us like a conquered country; it is a veritable invasion. One can no longer speak of the opera houses of Paris, but only the opera houses of M. Donizetti.”

Donizetti’s productivity might not have been so remarkable, and so enviable, if it had not come wrapped in a seemingly effortless gift for operatic characterization. His Daughter of the Regiment is unmistakably Italian in its melodic abundance, yet it captures the layered nuances and charm of its Gallic source. It’s almost irresistibly tempting to find a kinship between Donizetti and Marie based on their respective army experiences. Donizetti’s could probably have happened nowhere but Italy. Though he had demonstrated remarkable promise in early studies with several prominent music teachers, he enlisted in the army rather than support himself as a music teacher, as his father, Andrea, insisted he do; while the life of a composer seemed just too risky to satisfy Andrea’s concerns for his son’s future, Gaetano shuddered at the prospect of a career giving music lessons.

In the army Donizetti found time to compose opera on the side while serving honorably in a military regiment. Not only did his first opera, Enrico, Conte di Borgogna, mark its successful premiere during his army service; his second, Zoraide de Granata, received such favorable notice that he was discharged from the army without further military obligation. He was 25, and earned his chops as a working composer by producing a succession of successful comic operas in the style of Rossini during the next six years. (Rossini was five years his senior.) But the first major demonstration of his artistic maturity was the opera Anna Bolena, a romanticized treatment of the tale of Anne Boleyn that showed Donizetti’s flair for applying the rich sensuality of Italian compositional style to a story set far from Italian shores. Donizetti’s best-known work, Lucia di Lammermoor, would accomplish the same artistic union with a gothic romance drawn from a Waverly novel by Sir Walter Scott— an opera full of dark Scottish atmosphere and glorious Italian music.

As for Marie’s army experiences, they arise from the French tradition of the vivandières, typically young women attached to a military regiment who worked as canteen keepers. In keeping with their historic function of selling wine to the troops, they become known as cantinières in France, but in other countries in Europe and the Americas, the term vivandière was retained and the practice behind it was copied. In the U.S., the dramatic possibilities of a woman in the military milieu cropped up in ballads like “Jackaroe,” in movies like Shirley Temple’s The Little Colonel, and in our national fascination with true stories like that of Jennie Hodgers, who marched thousands of miles and fought dozens of battles for the Union disguised as a male soldier during the Civil War. But in the French tradition of The Daughter of the Regiment we see something subtler: an understanding of the complexity beneath the surface of masculine and feminine archetypes. Though Marie is plucky and tomboyish, and is fully at home as one of the boys, she is never less than fully a girl. As a womanly presence in the regiment, she creates comic complications while also giving rise to a certain sexual tension that becomes part of the daily reality of soldierly life: not a matter of resisting the impulse to flirt, but a continual reminder of home and family…of the half of the world left behind, comprised of sweethearts, wives, mothers and daughters. Perhaps the most famous example of this tension is the stunning moment in Jean Renoir’s great 1937 film La Grande Illusion when prisoners of war watch fellow-soldiers performing in drag in an amateur vaudeville show: Their raucous laughter turns to stunned silence and remembrance.

It is unknown whether the libretto for The Daughter of the Regiment, by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Jean-François-Alfred Bayard, was built around an original story line or drawn from an outside literary source. But no matter. In either case, the resulting opera masterfully layers the blunt comedy of Marie’s battlefield predicament with more nuanced comic elements. For example, it affords a natural comparison between the loneliness of military life and the loneliness of Marie’s mother, the Marquise of Birkenfeld, whose once-great love is a distant memory. And Donizetti took to this deeply French libretto with utter aplomb. After a shaky premiere The Daughter of the Regiment became wildly successful in Italy as well as in France, where Marie’s “Salut à la France” was adopted as a patriotic anthem during the Second Empire.

In America, The Daughter of the Regiment‘s fascinating performance history began in New Orleans in 1843. There, as elsewhere, it was a showcase for sopranos who possessed both the vocal resources and the personal charm to interpret the demanding title role. It entered the repertory of the Metropolitan Opera in 1901 with the great Marcella Sembrich as Marie, and though it was initially paired either with Cavalleria Rusticana or Pagliacci, by 1917 it stood on its own with a cast headed by Frieda Hempel, the versatile German soprano who introduced New Yorkers to Strauss’s Marschallin. With World War I still raging, Mme. Hempel interpolated Ivor Novello’s popular war song “Keep the Home Fires Burning (‘Till the Boys Come Home)” as part of Marie’s voice lesson. When Daughter was revived at the Met with the French coloratura Lili Pons as Marie during the Nazi occupation of Paris, the entire cast joined in the Marseillaise as Pons triumphantly displayed the tricolore at the opera’s finale.

More recently, The Daughter of the Regiment rejoined the repertory of the world’s major opera houses as part of the bel canto revival that began with Dame Joan Sutherland’s historic performances of another Donizetti masterpiece, Lucia di Lammermoor, beginning at Covent Garden in 1959. Though most audiences were not particularly interested in Dame Joan’s acting, in her Marie they discovered a gifted comedienne who was a good sport about self-parody in a role that played up her big, robust physique. What’s more, Dame Joan liked to surround herself with new artists she considered her equals, and in February 1972 in the Met’s new production of Daughter she introduced one of her discoveries to New York audiences: an unknown tenor named Luciano Pavarotti, whose galvanic performances restored the importance of Tonio’s role in the opera and earned Pavarotti the epithet “King of the High Cs.” Today, in Utah and around the world, we can expect The Daughter of the Regiment to amuse and to dazzle us thanks to their legacy.

Before the PX…

…there were cantinières — canteen girls like Marie, who survived the privations of war by meeting soldiers’ needs for merchandise and services they could get no other way. Camp-followers of this kind are probably as old as war itself; Bertolt Brecht’s “Mother Courage” is a character based on a historical camp-follower from about 1670. The value of this kind of civilian entrepreneurship to the to the military was officially recognized In France in the 18th Century. The official term vivandière was replaced by cantinière in 1793, giving rise to the Anglicized term “canteen girl”. Such terms were used interchangeably in France as well as in Spain, Italy and the U.S. through the 19th Century.

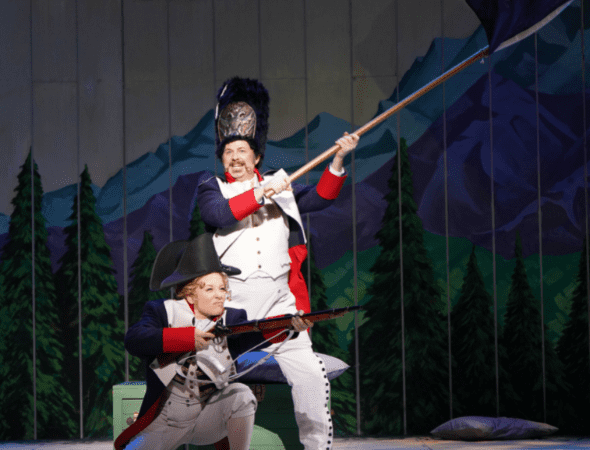

Photos of French cantinières in the Crimean War from the 1850s show attractive young women in chic-looking uniforms with fitted bodices and rows of bright buttons. Marie’s English cousin aboard the HMS Pinafore is “Little Buttercup,” usually costumed in a full-skirted dress and apron (and described by her love-interest, Captain Corcoran, as “pleasantly plump”). Despite the innocent winsomeness of both characters, the question of “fraternization” with the soldiers shadowed cantinières, as we see in the final moments of The Daughter of the Regiment — when Marie’s past as a cantinière proves shocking to the guests assembled for her wedding. In the end, love triumphs over snobbishness, in part because the Marquise herself has a past…leaving us to wonder whether she will belatedly find happiness with Marie’s father figure, Sergeant Sulpice!