The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs Online Learning by Dr. Ross Hagen“Opéra Électronique”

One of the hallmarks of Mason Bates’ musical career is his long engagement with electronic music and his multiple projects that aim to erase the boundaries between classical repertoire and electronic music. The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs relies on a combination of orchestral instruments and electronic music, announced early on with intense sub-bass drops and saw-wave pulses that pan across the stereo field. These electronic sounds, paired with an occasional acoustic guitar, become something of a leitmotif for Jobs over the course of the opera. It reminds a bit of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s score for The Social Network, another Silicon Valley biography, in which Mark Zuckerberg’s character is scored with a Swarmatron, a custom-made electronic instrument that generates distinctly unsettling microtonal tone clusters. While the Swarmatron stands out within a score that’s already heavily electronic, the electronic elements in The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs stand out by their mere presence in an orchestral work. Although electronic and electric instruments have been in use for nearly a century, the worlds of mainstream opera and orchestral music have been slow to accept them. This reluctance makes sense given opera companies’ predominant focus on existing repertoire. Yet beyond the major concert halls and opera stages one finds a relationship between art music and musical electronics dating back more than a century.

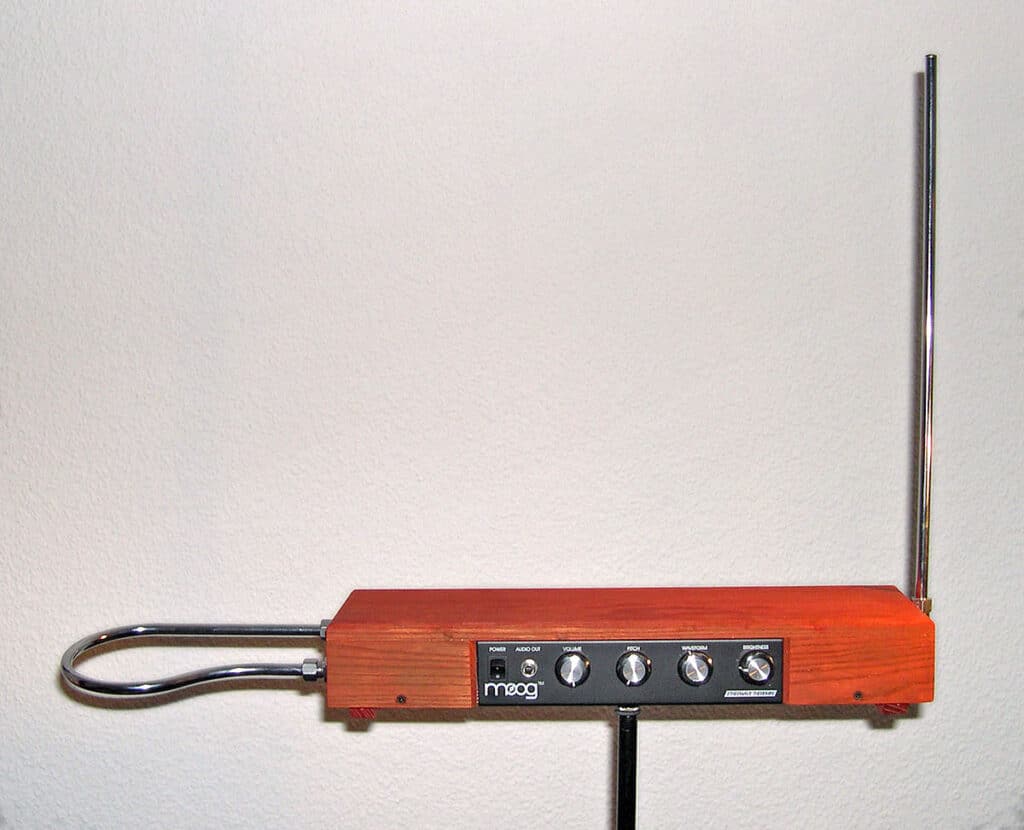

The history of electronics and electro-acoustics in art music takes a number of interesting turns, particularly because electronic music was initially almost solely the province of mid-century art music composers. This was partly a result of the expense of the necessary equipment and the difficulty of operating it, but also because the sonic world they created was largely inscrutable and alien to wider audiences. The early electronic instrument the Theremin had some success as a novelty instrument, although it was soon featured heavily in Miklós Rózsa’s scores for Spellbound (1945) and The Lost Weekend (1945) and Bernard Herrmann’s score for the sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still(1951). These film scores, and other electronic-heavy scores for science fiction films like Forbidden Planet and Delia Derbyshire’s electronic scores for the BBC series Dr. Who, established theremins and synthesizers as recurring musical tropes for psychological instability, extraterrestrial visitors, and all things weird and eerie. Art music composers of the 1950s and 60s, particularly those in the serialist camp, relished the opportunity to create music with extreme rhythmic precision and without the limitations of human performers (although the instruments had their own limits at the time). Works by composers like Otto Leuning and Milton Babbitt exploited this aspect fully, while Babbitt’s Philomel(1964) features a soprano who sings along with a taped background of synthesized sounds and her own distorted voice. It’s not all obscure though. The 1957-58 architectural sound installation Poéme Electronique in the Philips Pavilion at the World’s Fair Expo ‘58 in Brussels was intended as a celebration of postwar technological progress, in spite of the ultra-modern design by le Corbusier and the composer Edgard Varese’s score of disembodied sounds played over several hundred carefully-arranged speakers. The Pavilion is a forerunner of popular immersive (and also highly commercialized) art installations done by companies like Meow Wolf, and an early example of technology companies like Philips becoming artistic patrons.

The project that truly brought electronic music into the mainstream of both popular and classical art music was undoubtedly Wendy Carlos’ 1968 album Switched-On Bach, which also has the distinction of being the highest-selling classical music recording in history. The record includes interpretations of the third Brandenburg Concerto as well as preludes and fugues from The Well-Tempered Klavier, performed on a built-to-order Moog synthesizer. Rather than attempt to mimic the original instruments, Carlos’ arrangements exploited the tonal possibilities of the synthesizer itself. The Moog synthesizer of the time was monophonic, so creating the record required Carlos to individually track each part on multitrack tape along with her producer Rachel Elkind.¹ This tedious and exacting process somehow resulted in artistically successful and broadly appealing renditions of these Baroque works. Carlos followed this album up with other synthesizer albums in the 1970s, along with renowned scores for the films A Clockwork Orange(1971), which relied on synthesized arrangements of well-known classical music, particularly Beethoven, and Tron (1982). Carlos has been extremely reticent about making her music available on streaming music platforms, so I’m not able to link to anything here, but new generations of retro-minded electronic musicians have taken up her mantle, as in this charming Moog arrangement of J.S. Bach’s Sinfonia 42.

Electronic instrumentation has not generally been invited into large-scale classical genres like symphonies and operas, if only because those genres have historically been the most tethered to past repertory. There are some exceptions, though. One of the few large-scale operatic works that has included a significant amount of electronic instrumentation is the epic opera cycle LICHT by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, a seven-opera cycle (corresponding to the days of the week) that is assuredly one of the most radical and ambitious works in the history of opera. It employs an 8-channel electronic score in surround sound, various configurations of singers and acoustic and electronic instruments, along with dancers, videos, and releases of fragrances and mists. Perhaps most infamously, the “Wednesday” opera in the cycle features a string quartet playing in helicopters flying around the auditorium that is simultaneously broadcast back to the audience.

Even for works without the extreme demands of Stockhausen’s operas, performance logistics have undoubtedly played a role in concert halls’ reluctance to include electronic music. The logistics of electronic performance in any situation have often been somewhat fraught. Compared with classical music, there is typically no score apart from the studio recording, and there was often no way for the composition and recording process to be “performed.” Ensembles like the pioneering German techno group Kraftwerk devised ways to perform live in the 1970s and 80s, but it essentially involved taking their entire recording studio on the road. As a result of this complexity, it’s also not uncommon for performers of fully electronic music to strategically rely on backing tracks mixed with elements performed live. One particular concern is that while an error in acoustic performance might result in a wrong note, pressing the wrong button in an electronic performance could bring the whole event to a sudden grinding halt. Even when a group or performer might be performing live and in-the-moment, electronic instruments are typically somewhat inscrutable, with little connection between a performer’s action and a resulting sound. Modern laptop control pads (like the one Bates uses in his live performances) mitigate this problem and allow the laptop performer to integrate into a mixed ensemble without having to rely on backing tracks. Computer programs like MaxMSP developed ways to allow performers to control aspects of the computerized performance with their own gestures, as demonstrated in this performance of vocal and electronic works by the composer Pamela Z.

Mason Bates’ fusions between electronic music and classical music take a rather different trajectory than earlier electronic art music, as his background with electronic music is rooted in techno and other popular forms of electronic dance music (EDM) rather than the more avant-garde styles of the classical tradition. Bates sometimes performs EDM as DJ Masonic, and his nonprofit organization Mercury Soul produces events that purposefully combine classical repertoire with new music that mixes classical instrumentation with electronic performance. Bates’ main musical point of reference is the minimalistic techno style cultivated by producers and clubs in Detroit in the 1980s and Berlin in the 1990s. This particular style of EDM relies on rhythmic repetition and gradual change, which often makes it feel rather skeletal compared to other genres of EDM. The core of the sound is usually a Roland TR-808 or TR-909 drum machine, two instruments that Roland introduced in the 1980s that became foundational for EDM, 80s pop music, and hip-hop. Sometimes one of these drum machines is all that’s needed, demonstrated here by Detroit techno pioneer Jeff Mills on a TR-909. The limitations of these older drum machines make them ideal for repetitive loop-based composition and performance, although minimal techno producers also pursue rhythmic complexities akin to minimalist classical music by composers Steve Reich and Terry Riley.

Cross-pollinations between EDM and classical music in recent years have often taken the shape of re-orchestrations and remixes, such as the 1999 album Reich Remixed, in which various EDM artists remixed Steve Reich pieces. The Canadian musician Venetian Snares’ 2005 album Rossz Csillag Alatt Született is composed of numerous orchestral samples from Stravinsky, Mahler, and Bartok (among others) combined with “breakbeats,” drum parts sampled from old funk records and digitally processed and rearranged. For example, the second track “Szerencsétlen”is composed of samples from Bartok’s 4th string quartet accompanied by rearrangements of the famous “Amen Break.” Flowing in the other direction, one finds Philip Glass’s re-orchestration of renowned EDM composer Aphex Twin’s “Icct Hedral”. The celebrated new music ensemble Alarm Will Sound has also performed orchestrated versions of the Aphex Twin pieces “minipops 67” and “Cock/ver 10,” and an ensemble named Stargaze apparently created an arrangement of the Boards of Canada piece “Everything You Do Is A Balloon.” (Here are the original electronic tracks: “minipops 67,” “Cock/ver 10,” “Everything You Do is a Balloon”) Aphex Twin and Boards of Canada make sense as choices for such undertakings, though, as their music often includes lush soundscapes that translate well to chamber ensembles while Aphex Twin especially includes intricate and dynamic textural and rhythmic changes that are challenging and rewarding to perform (especially for drummers).

Bates has been hailed a pioneer in bringing these elements from minimal techno and EDM into the symphonic concert hall, most visibly in his symphonic work Mothership, in which he performs using a control pad and laptop alongside an orchestra and several improvisational soloists. Mothershipwas commissioned for the second iteration of the YouTube Symphony, an open-audition ensemble sponsored by the London Symphony Orchestra and directed by Michael Tilsson Thomas. The 2011 YouTube Symphony livestream was quite successful, garnering an audience of 33 million viewers, making it the largest live-streaming music concert at the time.

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs demonstrates how the perceptions and uses of electronic music have shifted in the last few decades, but it also shows how this can paradoxically undermine the intended programmatic effects of electronic sound. Half a century ago, the heightened strangeness of synthesized sounds and manipulated audio were certainly interesting on their own, but they also conveyed a sense of instability and Otherness. They not only soundtracked journeys to other worlds but also to the deepest recesses of our own inner thoughts, insecurities, and primal urges. However, these new sounds quickly became a mundane part of our soundscape, and what was once cutting edge now becomes comfortingly nostalgic and retro-futuristic. The inclusion of electronic sounds in The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is novel in the world of operatic orchestral music, but by now the electronic sonic palette Bates uses is also familiar and well-known to many listeners. Some effects, like the sub-bass drops and synth pulses in (R)evolution, are akin to the electronically-intensified sounds common in science-fiction and action films and in the famous title card for Lucasfilm’s THX sound system. The computerized elements in (R)evolution are used strategically and carefully, however, and with a good sound mix they blend into the overall soundscape, lending it an uncanny feeling in spots while taking center stage when called for.

¹ Roshanak Khesti, Switched-On Bach. New York: Bloomsbury, 2019.