The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs Online Learning by Dr. Ross HagenBe Here Now?: Opera of the Moment

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is only one representative work within a broader trend in modern opera that draws from events and persons within recent memory, in some cases involving persons who are still alive. This encompasses everything from Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, John Adams’ Nixon in China, Dr. Atomic, and the controversial The Death of Klinghoffer, Jake Heggie’s adaptation of Dead Man Walking, and Jonathan Dove and April DeAngelis’ Flight (produced by Utah Opera last season). It is a novel development, considering that opera and classical music more broadly is well-known for focusing on a relatively narrow canon of well-known works that are repeatedly produced. Hence the term “classic.” Yet for much of the history of opera prior to the 20th century it would have been a little odd to go to a concert and hear a program of music written well before the lifetimes of anyone present. Operas especially were often adaptations of stories, novels, and plays that might not be exactly “ripped from the headlines,” but were recent enough and well-known by audiences, and in some cases involved characters clearly based on actual people.

The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs and its cohort of modern operas is then partly a return to form for opera, even as it is a new development. The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs also shares some DNA with the Baroque and Classic-era operas in the opera seria genre in particular. These were typically heroic stories featuring figures of Greek or Roman history, and nearly always ended with a just and virtuous emperor or deity triumphing over the forces of evil. Even when the subjects were drawn from classical antiquity, the kings and aristocrats of the time clearly saw themselves mirrored in these narratives; there was even a conceit at the time for monarchs to be addressed by name as mythical figures like Zeus or Diana. Operas were not only a source of drama and entertainment, but also a vehicle for hagiography, much like modern authorized biographies and documentary films.

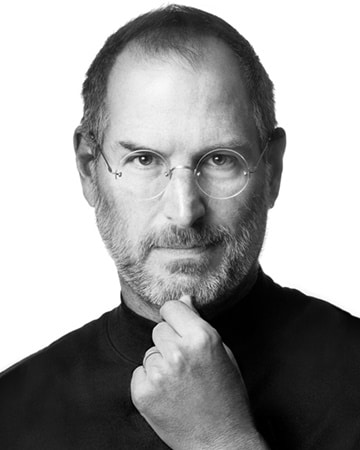

This side of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is at heart a conventionally heroic narrative centered on a Great Man® of the past, the sort of individualistic mythologizing that has been a hallmark of the American industry dating back at least to the days of Edison. The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs fits neatly within these tropes, featuring a Christmas Carol-esque retrospection leading an ambitious and egocentric main character to a final, redemptive understanding of the value of love and human connections. As is typical, he is assisted in this by the love of a patiently devoted woman who also “kicks his ass.” There’s also a lot of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, but with a workbench instead of a sled, although in that film the title character Charles Kane ultimately ends up unhappy, alone, and regretful. The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs also takes its place among the assortment of other biographical works about Jobs, including the 2011 authorized biography Steve Jobs and its 2015 film adaptation, and the 2015 unauthorized biography Becoming Steve Jobs. Jobs’ surviving family, friends, and colleagues have had significant disagreements over these biographies, although I’ve not yet found any similar commentary on the opera. The prominent disclaimer that (R)evolution does not intend to faithfully represent true events probably helped ward that off.

Although political figures of the last few generations obviously wield influence and power, the actions of corporations like Apple, Amazon, Google, and Facebook over the last generation have affected our lives and our experiences of the world in profound ways that would be the envy of any king, emperor, or deity. Perhaps one of the most singular things about The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is the fact that I’ve been listening to this opera and writing about it on machines that were initially devised by the opera’s subject. And the machines know it as well – immediately after I’d been reviewing the opera on Spotify during a long drive, my Amazon television at home quickly served up an advertisement for a classical music video channel I had never heard of…with a graphic featuring The Atlanta Opera’s production of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs.

The ubiquity and influence of Jobs’ company and their devices ultimately creates one of the key dilemmas that Bates and Campbell no doubt wrestled with while creating this opera. While other 21st-century American tech magnates like Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, and Larry Page and Sergey Brin initially built their empires on software platforms and algorithms, the previous generation of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were also steeped in the business of consumer electronics. Jobs’ persona exists not only in the software, but also in the physical machines, and the plot of (R)evolution makes it clear that Jobs recognized the importance of this. As a result, (R)evolution hits much closer to home than operas based on other recent historical figures or adapted from modern literature and/or film. To illustrate, I can recognize and appreciate the incredible influence of someone like Albert Einstein in the world I inhabit, but I’m currently within arm’s reach of (at least) three Apple devices. I carry one of them in my pocket and it counts how many steps I take each day, and I genuinely care about that number. It automatically sends those numbers to the other two, just in case. As a relatively by-the-book biography (or bio-opera?), (R)evolution has to acknowledge this situation somehow, so Bates and Campbell choose to simply face it head-on in the opera’s final scene. It makes for a sudden shift in tone, but there also may have been no other choice, given their subject.