The Creators of Carmen: Ludovic Halévy and Henri Meilhac

LIBRETTISTS

LUDOVIC HALÉVY (1834 – 1908)

HENRI MEILHAC (1831 – 1897)

It’s almost impossible to separate these two authors who were collaborators on plays and librettos for over twenty years. Grove’s Dictionary of Opera did, and Meilhac was awarded a mere paragraph! So, in the interest of space, I’ll combine them. But it’s important to remember that both had had previous collaborators before they met and that each continued extra-collaborational collaborations during those two decades. It’s safe to say that their assorted infidelities had no effect on their theatrical relationship!

Ludovic Halévy’s father, Léon, converted from Judaism to marry his Christian wife. Daddy, a civil servant, was respected in literary circles, though he never achieved much fame in whichever literary genre he tried – and, apparently, he tried them all! The Halévys were a cultured Parisian family. Léon’s brother, Jacques-Fromental Halévy, is known today – if he is known at all – as the composer of La Juive, a hugely successful opera when it was first performed in 1835. Gustav Mahler thought it “one of the greatest operas ever created,” and even Wagner praised it highly; it has not survived, though various tenors, including Enrico Caruso, and, more recently, Richard Tucker and Neil Shicoff, have advocated for productions. Uncle Jacques produced a daughter, Genivièvre, who would marry the promising young composer, Georges Bizet. The young Ludovic, thanks to his family background, and despite his poor academic performance, found employment in the French Civil Service. His heart, though, was in his writing.

In 1855 he had his first success with Ba-ta-clan, a one-act “Chinese Musical,” with music by Jacques Offenbach. The following year he wrote, with Léon Battu, the libretto for Le Docteur Miracle, which was assigned as the final project of a competition organized by Jacques Offenbach. The 19-year-old Georges Bizet was the co-winner, and his score was first performed on April 9, 1857.

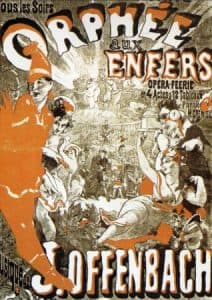

A year later Halévy collaborated with Hector-Jonathan Crémieux on a libretto for Jacques Offenbach. Orphée aux Enfers was a huge success; but, fearful that his association with an opéra comique might hinder his progress in his official career, he insisted that the credit and royalties be given to his collaborator. In 1864 the triumphant success of Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène (for which Halévy and Meilhac provided the libretto) allowed Halévy the financial security to resign from the Civil Service, which he did the following year, and to devote himself to writing for the theatre: some 27 librettos and 34 plays, not to mention some novels, overall – an astonishing output!

A year later Halévy collaborated with Hector-Jonathan Crémieux on a libretto for Jacques Offenbach. Orphée aux Enfers was a huge success; but, fearful that his association with an opéra comique might hinder his progress in his official career, he insisted that the credit and royalties be given to his collaborator. In 1864 the triumphant success of Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène (for which Halévy and Meilhac provided the libretto) allowed Halévy the financial security to resign from the Civil Service, which he did the following year, and to devote himself to writing for the theatre: some 27 librettos and 34 plays, not to mention some novels, overall – an astonishing output!

Collaboration seems to have been Halévy’s preferred method of working, and the success of Hélène was the start of an extraordinary working relationship with Henri Meilhac.

Meilhac, another Parisian, was born in 1831. Unsatisfied with his trade as a book-seller, Meilhac began contributing articles and cartoons to the satirical Le journal de rire, which resulted in his collaborating with various authors (excluding Halévy) on 15 librettos, the greatest of which was that, with Phillipe Gille, he wrote for Jules Massenet’s Manon, which premiered in 1884. He also contributed to 15 plays (again excluding his plays with Halévy).

La belle Hélène was followed by a string of successes, all with music by Offenbach: Barbe-bleue and La vie parisienne in 1866; La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein in 1867; La Périchole in 1868; Les Brigands in 1869. I mention Les Brigands (successful at its premiere, but not revived much these days) because, in 1871, an English version by W.S. Gilbert (of Gilbert-and-Sullivan fame) was published, though it wasn’t performed in London until 1889, not very successfully, and Gilbert himself was not satisfied with the result. Gilbert also adapted, twice, for the Victorian London stage, their 1872 play Le Réveillon: in 1874 it appeared as Committed for Trial; three years later, and with an extra act, it was given as On Bail. Neither version could compete with the German adaptation which became the basis of the greatest of Johann Strauss’s operetta, Die Fledermaus. First performed in April 1874, it remains the pinnacle of Viennese operetta.

The Franco-Prussian War, with its siege of Paris and the subsequent violent suppression of the revolutionary Commune, which had sprung up in response to the political situation, closed, not surprisingly, Parisian theatres. When they re-opened, Offenbach, given his German origin, proved not to be the draw he had been pre-war. Nor were the politico-satirical librettos (a category ignored by, or maybe unknown to, Polonius, in his catalogue of dramatic categories in Hamlet) – pieces in which he and his M/H librettists had been such masters, possible any more.

Over the span of about twenty years, Halévy and Meilhac collaborated on 14 librettos and 33 plays; their collected collaborations were published in eight volumes between 1899 and 1902. Both men were elected to the Académie Française: Halévy in 1884, and Meilhac in 1888. Meilhac died in 1897, Halévy in 1908.

©Paul Dorgan