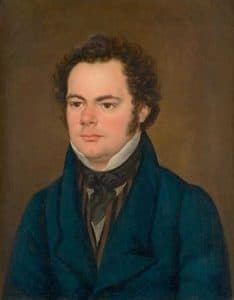

Sir Walter Scott (1771 – 1832)

Poor Sir Walter Scott! I doubt that any of his novels are required reading in any of today’s Eng. Lit. classes; but had there been a Best-Seller List in the late eighteenth/and early nineteenth centuries, he would have been consistently in the top ten. And not just for his “Waverley” novels. Before the first of them was published in 1814, his earlier collections of Scottish ballads and his long narrative poems had established him as the most successful poet of the day, not only in the British Isles, but also, in translation, throughout Europe.

Appropriately enough, Walter Scott was a Scot, born in Edinburgh on August 15, 1771. At the age of two he contracted a disease which left him lame (polio has been suggested), and he was sent to his father’s parental home at Sandyknowe in the Scottish Border area (presumably a healthier environment), where he absorbed from his Aunt Jenny not only the local legends, but also her speech patterns in the telling of those tales. In 1783 he was accepted as a student of classics at the University of Edinburgh. A twelve-year-old was allowed to enroll in classes at a distinguished University? Three years later he was apprenticed to his father’s legal office to become “a Writer to the Signet,” i.e., someone who would plead a client’s claim in court. And thus began his lawerly career. He returned to the University for the 1789-90 academic year; his studies there, followed by his subsequent practice, were sufficient to allow him to be admitted, in 1792, to the “Faculty of Advocates,” which meant he could be a part of any case before any of the courts of Scotland – and there were many levels of those courts! In 1799 he was appointed a Sheriff-Depute, based in Selkirk in Southeastern Scotland. (Gotta love those Scottish legal terms: “Writer to the Signet”; “Faculty of Advocates”; and “Sheriff-Depute”!)

But writing poetry seemed more attractive than lawyering. In 1796 his first poems were published: Translations and Imitations from German Ballads; the last of the seven is an English version of Goethe’s Erlkönig, which Schubert (aged 18), among other composers, set so memorably: the others not so memorably! In 1802 and 1803 appeared the three volumes of The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, a collection of 96 poems and ballads which, until then, existed only as oral tradition – thank Aunt Jenny for fostering that interest! In 1805 his first original poem, the 6-canto The Lay of the Last Minstrel, was a huge success. Marmion, published in 1808, was another 6-canto success. This was followed, two years later, by yet another 6-canto poem: The Lady of the Lake. What was his attraction to the 6-canto form?

At school, one of his friends was James Ballantyne, who later went on to establish a printing house in Kelso, where he was born, and where he edited, printed and published the local newspaper. Did you know that there was a difference between a Printing House and a Publishing one? Me neither. And that sometimes the Printing House published what they printed, though more often they would just print the text sent to them and send it to be published by another company? Me also neither. Complicated, isn’t it! For Scott it became more so: probably worthy of a Dickens novel! In 1803, thanks to an infusion of cash from Scott, James transferred his business from Kelso to Edinburgh. All went well, with Ballantyne printing all of Scott’s novels, until a banking crisis hit England in the 1825 – see below!

In 1814 Scott abandoned the 6-canto poem for the historical novel. Waverley, dealing with Scottish history in the mid-1750’s, was rapturously received: its first printing of 1,000 copies sold out in two days; within a few months it had reached a fourth edition. It was followed by an almost yearly series of twenty novels, all of which were set in the past: mostly Scotland’s, though a few in England’s. Despite the success of these novels, Scott continued his lawerly career as “Clerk of Session” (Scotland’s highest civil court) and Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire. Which must have been a particularly law-abiding county to allow him the time for all this writing!

Ironically, neither his lawerly career, nor his literary success, contributed to his knighthood: the reward for his discovery of the Scottish Crown Jewels. Without going into too much historical detail, Scotland remained a sovereign state when their King James VI, the son of Mary Stuart (Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda) became England’s James I after Queen Elizabeth I (daughter of Donizetti’s Anna Bolena, and heroine in her own right of two Donizetti operas: Roberto Devereux; and the Scott-derived Elisabetta al Castello di Kenilworth – also known as Il Castello di Kenilworth) died in 1603; Scotland stayed sovereign until the 1707 Acts of Union united Scotland and England under one crown. In 1649 King Charles I was convicted of high treason by Oliver Cromwell’s ruling party in Parliament, and was executed. Cromwell’s party then established a so-called “Protectorate” – a kind of no-monarch republic, which ordered the destruction of all royal regalia. But meanwhile the sovereign state of Scotland crowned, with the so-called “Honours of Scotland,” Charles’s son and heir as their King Charles II. Cromwell ordered the destruction of all royal regalia, but the canny Scotts hid their jewels in various places until Scott and others discovered them in the deeps of Edinburgh Castle in 1818. The future George IV (son of the titular character of Alan Bennett’s play The Madness of George III; and the later movie The Madness of King George) conferred on Scott the title of “Baronet.” He was now SIR Walter Scott.

Despite this royal recognition, Scott’s novels continued to be, as they had been from the start, published either anonymously: “By the author of Waverley,” or pseudonymously: The Heart of Midlothian, for instance, which appeared in July 1818, was credited to “Jedediah Cleisbotham, Schoolmaster and Parish-clerk of Glendercleugh.” In early-nineteenth-century England, poetry was considered a higher literary calling than the novel, so perhaps Scott felt that his 6-canto-poem fans would have felt betrayed had they known of his switch to the novel; perhaps, too, he might have felt that writing historical novels was beneath his lawerly dignity. For whatever reason, it wasn’t until 1827 that Scott finally came out as the author of these novels, though it seems that both critics and savvy readers were aware of his identity from the start. Jane Austen complained in a letter written in the year of Waverley’s publication that “Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones…He has Fame and Profit enough as a Poet…”

Maybe his admission was prompted by the stock market crisis in 1825 in England which eventually reached Scotland and resulted in the collapse of the Ballantyne printing business. As their only financial partner, Scott stood to owe some $11,000,000 (in today’s money) to the company’s various creditors! Refusing to declare bankruptcy and the offered financial help from friends (including King George IV), Scott, determined to write himself out of debt, placed his assets – his house and his income – in a trust owned by his creditors. When he died, in September 1832, money was still owing, but the continued sale of his novels soon erased his debts.

Had there been, in the early years of the nineteenth-century, any kind of copyright laws, Scott could have quit his lawerly day-job and devoted himself solely to his novels, earning even more money from the sale of the author’s various ownership rights which are taken for granted today: translation rights (France, Germany and Italy gobbled up his writings!); stage adaptations (in the century after Rob Roy was published, for instance, there were over 900 of them!); composers’ use of poems to turn into songs; not to mention composers’ use of poems and novels to turn them into operas. But there weren’t, so he didn’t.

Joseph Mitchell, in his The Walter Scott Operas, reckons there are “approximately fifty operas based on the Waverley Novels.” He includes Rossini’s La donna del lago which was based on Scott’s poem The Lady of the Lake; but he ignores the “numerous” so-called ‘musical dramas’ by the likes of Sir Henry Bishop in which the “tuneful ditties” are assigned to lesser characters and the action is propelled through dialogue; Bishop’s adaptations usually appeared in London (often at Covent Garden) within a year of the novel’s publication. “Next to Shakespeare…” he writes at the end of his Introduction, “…he inspired more operas than did any other single writer.” The composers Mitchell discusses include Italians: Donizetti (of course!), Rossini, and Bellini, among many others; French: Adolphe Adam, François Adrien Boieldieu, Daniel Auber, and Georges Bizet; Germans: Friedrich von Flotow, Otto Nicolai and Heinrich Marschner (the operatic link between Weber and Wagner). The British Isles are represented by the English-born Sir Arthur Sullivan, the Scottish-born Hamish MacCunn, and the Irish-born Michael Balfe. Denmark’s now-forgotten Ivar Frederik Bredal is included; as is America’s Reginald De Koven.

Outside of Mitchell’s scope are the composers who set various Scott poems as songs. You may come across references that both Haydn and Beethoven set some of those them as songs. What I’ve been able to discover is that both composers were highly paid by George Thomson, the publisher, to provide accompaniments (either for solo piano, or for a piano-violin-cello combination) for the folk-song melodies he sent them. The texts, whether traditional ones, or “refined” by the likes of Robert Burns and Scott, were later added to the accompaniments sent back to him: neither Haydn nor Beethoven were aware of the words that would be added to the tune they were working on; so, strictly speaking, neither of them “set” any of Scott’s poems.

Franz Schubert was the first composer, and the greatest one, to translate Scott poems into song. Adam Storck’s German translation of The Lady of the Lake was published in 1819. In 1825 Schubert set seven of the songs which were published the next year as Liederzyklus vom Fräulein vom See, Op. 52: three were for solo female voice and piano; two for baritone and piano; one for a male voice quartet; and one for a female choir. The sixth poem of the cycle is probably the most familiar of all Schubert’s melodies. We usually hear it sung to the Catholic Latin prayer “Ave Maria,” but that text was adapted, and distorted, to fit Schubert’s vocal line. Yes, Ellen, Scott’s heroine, prays to the Virgin Mary, but her opening words, “Ave Maria,” are the closest the Catholic Latin gets to Scott! Sometime that same year he set an unknown German translation of a song (“Lied der Anne Lyle”) sung by the heroine of A Legend of Montrose (1819); “Gesang der Norna”, also composed in 1825, came from The Priate (1822); both songs were published together, as Op. 85, in 1828. The following year produced “Romanze des Richard Löwenherz” to a translation by Karl Ludwig Methusalem Müller which had been published in Leipzig 1820. The song is sung by the disguised Richard the Lionheart in Ivanhoe (1820). Was it possible that a German translation of Scott’s novel was published in the same year as its first publication in England? Especially by a writer whose only connection to Scott (at least on Google) is as the author of this translation? Two published sources I consulted (John Reed’s The Schubert Song Companion, and Graham Johnson’s exhaustive, and exhausting, 3-volume Franz Schubert: The Complete Songs) are confident that the German translation was published in 1820. Johnson is more confusing: he prints the German text, with a translation, and then adds Scott’s English text; under which he gives us the following: “Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), translated by KLMM (1771-1837); and then “poem written before 1820”. But whose poem? I’ve seen no evidence that Scott had published the poem earlier, as a separate entity, and then incorporated it into Ivanhoe. No poem, no translation! So how could Müller have translated the poem before it was published in England? Might he have had pre-publication access to Scott’s novel, so that his German translation would be published simultaneously with the original English one? Not very likely, given Müller’s literary obscurity. Schubert, of course, didn’t care (so perhaps neither should we): he found a text which inspired music, and followed his instincts!

Franz Schubert was the first composer, and the greatest one, to translate Scott poems into song. Adam Storck’s German translation of The Lady of the Lake was published in 1819. In 1825 Schubert set seven of the songs which were published the next year as Liederzyklus vom Fräulein vom See, Op. 52: three were for solo female voice and piano; two for baritone and piano; one for a male voice quartet; and one for a female choir. The sixth poem of the cycle is probably the most familiar of all Schubert’s melodies. We usually hear it sung to the Catholic Latin prayer “Ave Maria,” but that text was adapted, and distorted, to fit Schubert’s vocal line. Yes, Ellen, Scott’s heroine, prays to the Virgin Mary, but her opening words, “Ave Maria,” are the closest the Catholic Latin gets to Scott! Sometime that same year he set an unknown German translation of a song (“Lied der Anne Lyle”) sung by the heroine of A Legend of Montrose (1819); “Gesang der Norna”, also composed in 1825, came from The Priate (1822); both songs were published together, as Op. 85, in 1828. The following year produced “Romanze des Richard Löwenherz” to a translation by Karl Ludwig Methusalem Müller which had been published in Leipzig 1820. The song is sung by the disguised Richard the Lionheart in Ivanhoe (1820). Was it possible that a German translation of Scott’s novel was published in the same year as its first publication in England? Especially by a writer whose only connection to Scott (at least on Google) is as the author of this translation? Two published sources I consulted (John Reed’s The Schubert Song Companion, and Graham Johnson’s exhaustive, and exhausting, 3-volume Franz Schubert: The Complete Songs) are confident that the German translation was published in 1820. Johnson is more confusing: he prints the German text, with a translation, and then adds Scott’s English text; under which he gives us the following: “Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), translated by KLMM (1771-1837); and then “poem written before 1820”. But whose poem? I’ve seen no evidence that Scott had published the poem earlier, as a separate entity, and then incorporated it into Ivanhoe. No poem, no translation! So how could Müller have translated the poem before it was published in England? Might he have had pre-publication access to Scott’s novel, so that his German translation would be published simultaneously with the original English one? Not very likely, given Müller’s literary obscurity. Schubert, of course, didn’t care (so perhaps neither should we): he found a text which inspired music, and followed his instincts!

Other composers who set Scott’s texts include the Mendelssohns (both Felix and his sister Fanny); Max Bruch (composer of the great G minor Violin Concerto); the Danish composer Adolf Jensen; and, of course, a slew of British composers.

By the end of the nineteenth-century, Scott’s literary star had sunk very low, and a literary critic could probably explain this huge drop in popularity to the achievements of his younger contemporaries: Jane Austen (1775-1817); Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865); Charles Dickens (1812-1870); Anthony Trollope (1815-1882); and those various Bronte girls (1816-1855 encompasses the lives of all three of them!) Who seized on his popularization of the novel form, and developed it, in their various ways, as a medium in which real life could, or might, be discussed on the page. Readers began to prefer these novels (fiction though they were, but based in a reality they would understand) to Scott’s “historical-romantical” output, which was based on a nostalgic evocation of a past none of them could now relate to.

Although relatively few book lovers read him today, we music-lovers owe Scott a lot: Schubert’s “Ellen” songs (which include his Ave Maria); Rossini’s La donna del lago; Bellini’s I Puritani; Bizet’s La jolie fille de Perth; and, of course, the main reason for this essay: Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor.

©Paul Dorgan