Romeo & Juliet Online Course by Ross HagenPart 1- Charles Gounod Biography

by Ross Hagen

Charles Gounod was born in Paris in 1818 into an artistic family; his father was a painter and engraver and his mother was a pianist and visual artist. Following his father’s death in 1823, Gounod’s mother supported the family by starting a piano teaching studio. As a student, he studied with a rather eclectic range of teachers, and in 1839 ultimately won the Prix de Rome, a prestigious scholarship that allowed the winner to spend several years in Rome. Although he was apparently unimpressed by the current operatic offerings in the city, he much admired the city’s cultural legacy and its musical heritage, particularly the sacred works of Palestrina. When he returned to Paris in 1843, he took up a position as maître de chapelle at the Séminaire des Missions Etrangères, writing sacred music until 1847, when he left for a short-lived attempt at seminary studies.

After several years, Gounod was introduced to the singer Pauline Viardot and her husband, the impresario Louis Viardot, a connection that proved to be crucial for the advancement of his career. Pauline Viardot in particular secured him his first commission at the Opéra, Sapho (1851) and sang the title role, although the opera was unfortunately not particularly well-received. Unfortunately, the opera did not particularly conform to the conventions of French grand opera at the time, and the musical style was in some ways an pastiche of disparate traditions from France and Italy. Further collaborations with the Viardot family and their circle were scuttled by Gounod’s April 1851 marriage to Anna Zimmermann, the daughter of Pierre-Joseph Zimmermann, an accomplished piano professor from the Conservatoire. The impetus for the rift between Gounod and the Viardots are somewhat hazy, but the most likely reasons were rumors about adulterous liaisons between Gounod and Pauline Viardot.

Pauline Viardot

Following his marriage, Gounod became the director of the Paris Orphéon, part of a network of French singing societies made up of men from the working class and lower bourgeoisie, and the director of vocal instruction in Parisian public schools. In 1852, he also received another opera commission for La nonne sanglante, with a libretto by Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne, two of the main architects of the French grand opera style. Unfortunately it was not a success, but Gounod’s patriotic choral works with the Orphéon and a pair of popular symphonies, along with his professional contacts, ensured that his star would continue to rise.

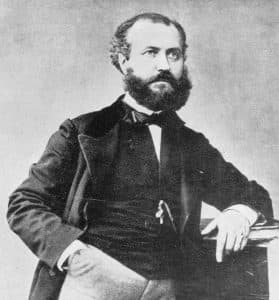

Charles Gounod in 1859, the year of the premiere of Faust

Gounod’s first major operatic hit, Faust (1859), at first looked to be another failure as its more progressive elements divided critics and audiences. Although Gounod’s fellow composers and critics often appreciated the opera’s bold strokes, stylistic heterogeneity, and Gounod’s attention to prosodic concerns (likely drawn from his experience writing and performing art song), other factions of the press were fairly hostile. Following the closing of the opera, Gounod reset the spoken dialogue as recitative with the idea to seek performances abroad, a plan that came to fruition when the publisher Antoine de Chaudens bought the rights and took the opera on tour through Germany, Italy, Belgium, and England. When it returned to Paris in 1862, it was chosen to open the new hall of the Théâtre-Lyrique by the director Léon Carvalho, who had overseen the opera’s development during his first term as director. This time it was a massive hit. Its success encouraged Gounod to write five more operas over the 1860s: Philémon et Baucis (1860), La colombe(1860), La reine de Saba (1862), Mireille (1864) and Roméo et Juliette (1867). The success of Faust and particularly Roméo et Juliette in 1867 also increased demand for his steady output of devotional works and mélodies, making this time period essentially the apex of his career. Oddly enough, the operas written between Faust and Roméo et Juliette did not do well, but this series of failures apparently didn’t affect Gounod’s reputation that much.

Following the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Gounod moved his family to England as a part of wave of refugees and focused his compositional work on small-scale composition for the English sheet music market. Gounod also became friends with the English soprano Georgina Weldon, and ultimately he and his wife began living with the Weldon family. Georgina’s increased presence in Gounod’s personal and business affairs estranged him from his wife Anna and strained relationships with his publishers until he broke off ties with her in 1874 and returned to France. The end of their friendship (or perhaps more than friendship?) was notably acrimonious and became litigious over the return of some manuscripts that he had left at the Weldon household. In 1877, Gounod’s new opera Cinq Mars was produced at the Opéra-Comique, but was a failure in spite of its lavish production and the promise of a triumphant return to the stage of such an eminent composer. Essentially, it seemed to reviewers that Gounod’s style, however progressive for its day, had become outmoded and obsolete. After several other abortive attempts to reclaim his early success, Gounod essentially retired from the stage in the early 1880s and produced no new operas before his death in 1893.

Utah Opera Company production of Romeo & Juliet, October 2005, Kent Miles

Although Gounod is for many simply the composer of Faust and Roméo et Juliette, his output also included a number of secular songs in French, as well as ones written in English and Italian. In these songs, it is evident that Gounod had ambitions to put French song on an equal footing with the German lied in terms of its expressiveness and attention to poetic detail. In addition, Gounod wrote a number of works for a cappella Orphéon choirs with a similar ear towards using music to evoke the scenes and emotions of the text. Gounod also wrote numerous sacred works, including 21 masses, three oratorios, along with cantatas, motets, and similar works. As is often the case with religious music, Gounod generally tempers the tendencies towards chromaticism and musical lushness that permeate his secular works in favor of a more austere style. However, some of his works, particularly the 1855 Messe solennelle de Sainte Cécile, do utilize the more chromatic musical vocabulary of the 19th century on occasion.

Ross Hagen is an Assistant Professor in Music Studies and the Music General Education coordinator at Utah Valley University.

Giroud, Vincent. French Opera: A Short History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Huebner, Steven. “Gounod, Charles-Francois.” Grove Music Online (2001).