Romeo & Juliet Online Course by Ross HagenPart 4- Commentary on the Opera’s Story

by Ross Hagen

Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette follows the plot of Shakespeare’s play faithfully, and the five-act structure of grand opera allows it to mirror the structure of the play fairly closely. However, a number of the supporting roles are significantly diminished and the ending introduces a dramatic twist. Rather than having Romeo die before Juliet awakens from her potion-induced sleep, the librettists Jules Barbier and Michel Carré altered Shakespeare’s ending so Juliet would awaken after Romeo has taken poison but before it takes effect. Thus, the opera could end with a tragic duet, allowing the two to die together at the end as opposed to having separate individual deaths as in the original play. Indeed, a number of popular stage versions of Romeo and Juliet made this change as well, and Bellini’s opera does the same. Gounod’s opera also leaves out the final denoument in which the Capulets and Montagues are reconciled after the deaths of their children. As a result, the final curtain follows immediately upon their death, mirroring the blunt endings of many other operatic tragedies.

As might be expected given its subject, Roméo et Juliette provides a number of opportunities for duets between the title characters, and indeed there is one featured in nearly every act. Juliet’s arietta from the first act, “Je veux vivre” is also a mainstay for operatic sopranos. However, at least one British critic, Sutherland Edwards of the St. James Gazette, argued that in doing so it diluted the drama:

“Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, in which the composer is always pleasing, though seldom impressive, might be described as the powerful drama of Romeo and Juliet reduced to the proportions of an eclogue (a pastoral poem) for Juliet and Romeo. One remembers the work as a series of very pretty duets, varied by a sparkling waltz air for Juliet…”

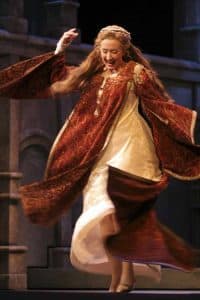

Utah Opera Company production of Romeo & Juliet, October 2005, Kent Miles

One might find an obvious rejoinder to Mr. Edwards in the fact that such dramatic winnowing would be necessitated by the specific demands of opera as opposed to spoken drama. Perhaps most crucially, it simply takes a lot more time to make it through the text of a sung drama, so cuts would be needed. Indeed, an operatic adaptation that simply set the full text of a Shakespearean drama to music would likely be unbearably long, and the various side-plots and secondary characters would potentially wind up feeling muddled and unfocused rather than creating dramatic depth. In creating an effective opera out of a literary or theatrical source, the plot must often be distilled somewhat in order to maintain dramatic focus and momentum. With this in mind, it makes sense to keep the action and the music focused on Romeo and Juliet, even if it potentially makes the rest of the opera feel like connective tissue between their featured numbers. Although even then, the inclusion of so many tenor-soprano duets flirts with monotony, were they not so well-composed. And indeed, the opera scholar Steven Huebner suggests that the notion of an opera built around a series of intimate duets might have had a special appeal for Gounod (1990).

If needed, there is an English translation of the libretto here.

Utah Opera Company production of Romeo & Juliet, October 2005, Kent Miles

The opera begins with Shakespeare’s prologue (“Two households, both alike in dignity, in fair Verona, where we lay our scene”…), which created an interesting dramatic opportunity for Gounod to enhance the typical operatic overture by adding a chorus. The original concept was for the curtain to remain closed and for the chorus to sing from the wings, but during the dress rehearsals Gounod decided to instead have the principals perform it with the curtain raised, evidently after some persuasion from the theatre manager Léon Carvalho. From there, the first act begins with an appropriately sumptuous masked ball in the house of the Capulets, and introduces first Juliet, Tybalt, Paris, and Juliet’s father Capulet. Mercutio and Romeo debate whether to reveal themselves, and Romeo argues against confrontation, noting mysteriously that he had had a dream. His friend Mercutio mocks him lightly and invokes the dream-influencing fairy Queen Mab in a long ballad (of course, in a French paraphrase of Shakespeare’s original monologue). Romeo is in a melancholic mood over another woman until he sees Juliet and is stricken. Mercutio and his friends quickly hustle Romeo off before Juliet and her nurse Gertrude enter, arguing lightly over Juliet’s impending wedding to Paris. Juliet then sings her showpiece “Je veux vivre,” in which she expresses her desire to remain in the carefree days of her youth rather than resigning herself to marriage. Romeo and Juliet then meet and interact for the first time, singing their first duet of the opera. They are interrupted by Tybalt, and Romeo learns for the first time that the girl he has been wooing is Capulet’s daughter. Although Romeo is masked, Tybalt recognizes his voice and, although a fight is avoided, he swears eventual revenge.

The second act is a quiet and intimate contrast to the rousing first act, perhaps rather like the second movement of a typical classical symphony. It finds us in Juliet’s garden for the famous balcony scene, after an introductory chorus of Romeo’s friends wishing him luck. Romeo sings a cavatina on his famous monologue (“What light from yonder window breaks?…”) and he and Juliet have a brief scene before being interrupted by the Capulet servants, who are looking for the Montague page Stephano. This is another invention of the opera that is nowhere in the play, but it breaks up the sombreness of Romeo and Juliet’s duet. Juliet’s nurse Gertrude sends them off, and then Juliet and Romeo continue their second duet of the opera.

Act Three opens in Friar Laurence’s chamber. Romeo arrives and confesses that he is in love, and then reveals that he has brought Juliet and Gertrude with him in order that he and Juliet might wed. Gertrude waits outside while Friar Laurence marries the couple in a scene that is not staged in Shakespeare, but here perhaps adds a religious element that is underscored at the opera’s conclusion. The second scene is a proper grand opera spectacle featuring a huge brawl between the Capulets and Montagues. It opens with Stephano, Romeo’s page outside the Capulet house, singing an aria meant to provoke the Capulet men into a fight. The servants and Gregorio come out and give him the fight he’s after. Benvolio and Romeo’s friend Mercutio enter and take up the fight upon seeing the boy Stephano swordfighting with Gregorio, sparking Tybalt, Paris, and others to enter the fray. Romeo gets between Tybalt and Mercutio, but as the melee continues Mercutio is cut by Tybalt and dies, prompting Romeo to go after Tybalt in his rage and kill him. At this the fighting stops, and although Benvolio urges Romeo to flee, he instead decides to stay and face his fate. The Duke enters with his retinue and the Capulets demand justice, while Romeo pleas that he was avenging his friend. The Duke exiles Romeo and the act ends with a massive choral finale, although Romeo also declares that he will see Juliet again even if it means his death.

Utah Opera Company production of Romeo & Juliet, October 2005, Kent Miles

The fourth act begins in Juliet’s room with one of the couple’s featured duets. Juliet forgives Romeo for Tybalt’s death and then they embark on the famous passages in which Romeo notes that he hears a lark, the bird of morning, while Juliet insists on it being a nightingale in order to delay Romeo’s departure. After Romeo leaves, Gertrude enters with Capulet and Friar Laurence, and Capulet reminds Juliet that Tybalt’s dying wish was for her to marry Count Paris. Friar Laurence then gives her a sleeping potion which she can use in order to feign death, avoid the wedding, and escape with Romeo. Juliet worries that it might not work and she would still have to marry Paris, or that she would never wake up from it, but she determines to take the risk. Her aria is followed by a short ballet.

Utah Opera Company production of Romeo & Juliet, October 2005, Kent Miles

The second scene in Act Four is one of the opera’s indulgences in drama and spectacle that departs significantly from the original source material. In the original play Juliet takes the potion the night before her planned wedding to Paris, so she appears to be dead in the morning. In Gounod’s opera, however, the wedding is underway, and Juliet passes out and appears dead right as Paris is about to put the wedding ring on her finger. This change allows for the staging of an elaborate wedding procession, complete with an onstage band, and a dramatic onstage “death” right before the Act Four curtain falls. The production used for this synopsis deleted this second scene, and it seems that is a common choice. Indeed, this was the intent in Gounod’s original drafts before second thoughts led him to indulge the Parisian audiences’ appetite for spectacle. In piano reductions from the 1870s and 80s this scene was often listed at the end as supplemental, and while the wedding “death” is an interesting idea, it was probably a bridge too far. In terms of momentum, the ballet after Juliet’s aria can effectively serve as a scene change and lead right into Romeo’s discovery of Juliet’s body.

The final act takes place in the underground tomb where Juliet’s body has been laid. Friar Laurence learns that his note to Romeo was not delivered, and we then see Romeo entering Juliet’s tomb unaware of the fact that she is merely “mostly dead.” Romeo sings a lament and then drinks poison from a flask right before Juliet begins to awaken. As she regains consciousness, they have a brief moment of happiness before Romeo reveals that he drank poison before she awoke, thinking she was dead. They sing a final duet as Romeo weakens, including a recall of the lark/nightingale conversation from the previous act, before Juliet pulls out a dagger and stabs herself. She declares her joy of dying with Romeo, the pair ask for forgiveness and salvation, and then they die. Although this religious aspect is nowhere in Shakespeare’s original, it is in keeping with Gounod’s own personal religiosity.

Ross Hagen is an Assistant Professor in Music Studies and the Music General Education coordinator at Utah Valley University.

Huebner, Steven. The Operas of Charles Gounod. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

Rosenthal, Harold Two Centuries of Opera at Covent Garden. London: Putnam, 1958.