The Merry Widow Lesson: What’s Operetta, Doc?

Operetta is defined broadly as an opera that is lighter in tone and shorter than other operatic fare. Indeed, one of the main circumstances that drove the creation of operetta was the desire for short comedic works that would either provide comic relief between the acts of a more serious opera or as a part of a full operatic season. In this vein, an important antecedent is the Italian intermezzo, a one-act comedic genre that became quite popular in the 18th century. Of these, Pergolesi’s La Serva Padrona (1733) is by far the most famous and played a significant role in spreading the style of Italian opera buffa across Europe. Generally, opera buffa and operetta both play off of the operatic conventions of their times, often gently satirizing opera itself for the benefit of knowledgeable audiences.

Operetta also drew a lot of influence from the wide variety of musical traditions over the centuries that have eschewed operatic recitative in favor of combining spoken dialogue and dance with musical numbers. In many cases the music in these traditions might consist primarily of popular melodies set to new words, as in the French comédie en vaudeville or the 18th century English ballad opera. Both of them are rather like modern “jukebox musicals” in that respect. Both comédie en vaudeville and ballad opera were often bitingly satirical, skewering political and social elites and the opera genre itself. John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728) in particular satirized the lofty Italian opera seria that had come to dominate London’s opera stages with austere stories of honor and duty focusing on Roman emperors and gods. The Beggar’s Opera instead featured an assortment of thieves, prostitutes, and other unsavory types, and aimed to skewer politicians, social elites, and social injustice in general. Indeed, its final line, “That the lower People have their Vices in a Degree as well as the Rich, and are punished for them,” drives the point home by implying that the wealthy get away with things that the poor are often harshly disciplined and incarcerated for. The music of The Beggar’s Opera is an assortment of adapted folk melodies, popular songs, hymns, and some opera arias, providing an antithesis to the virtuoso castrati singers featured in opera seria. Operetta retained this initial satirical bent, and as a result many 19th and 20th century operetti are full of topical references poking fun at current events or public figures. Of course, one of the side effects of such topical humor is that many of the gags that might have been uproarious for previous generations may be somewhat lost on 21st century audiences.

However, the primary target of operetta’s ribbing tended to be opera itself. By the mid-19th century, many operas had become massive spectacles, as in the Parisian grand opera tradition, and Richard Wagner’s operas came laden with sublime transcendence and philosophical heft. Operetta provided a steam valve of sorts for poking fun at the pretentiousness and often sheer ludicrousness of opera, but did so for the benefit of a bourgeois audience who knew opera well and would thus get the jokes. This kind of mockery is not usually particularly critical or subversive; it’s more a sort of friendly caricature that actually serves to endorse and sustain the status quo. (Taruskin 644-55) It’s akin to a comedy roast, in which people take turns good-naturedly joking at the expense of the guest of honor. Of course, some music critics inevitably don’t understand the affectionate nature of the satire and take stringent offense, not realizing that in doing so they serve as unwitting publicists (although some more self-aware critics might recognize that outrage and indignation might actually be the main product they are selling). It is also worth considering that satirical genres of music, art, and theatre often get a pass for their calculated amorality and mild sacrilege, even if more serious artworks are stringently policed and censored. (646) After all, farces and burlesques have an implied “just kidding” following every moment of political or social criticism. It’s also possible that a stringent or censorious response from the government or other institution might make them seem weak or vulnerable because they can’t take a joke. At the very least, such an attempt to suppress something often simply calls more attention to it. In the case of operetta, its gentle burlesque of opera tends to tacitly acknowledge the popularity and power of opera and its institutions and patrons.

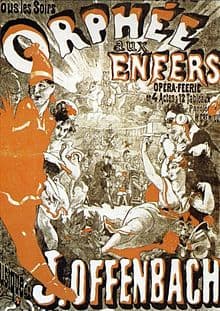

In terms of defining operetta as a genre separate from opera, the Parisian composer Jacques Offenbach (1819-80) deserves much of the credit. In particular, his 1858 opéra-bouffe Orpheé aux enfers (“Orpheus in Hades”) provides an excellent example of the approach which he bequeathed to later operetta composers like Franz Lehár. Offenbach’s lampooning of opera begins even with his very choice of topic. The Orpheus of Greek myth was a legendary musician who attempts to retrieve his dead wife Eurydice from the underworld through the persuasive power of his music. He succeeds in gaining her release and is instructed to not look back at her until they are both in the upper world, but he forgets and looks back and she disappears back into the underworld. Orpheus came to embody the ethical and emotional power of music, and as such several of the earliest proto-operas in the 17th century were based on his myth, along with later operas by Monteverdi and Gluck. What better subject for a musical farce than something so tied to opera and also so baldly lofty and self-righteous?

In Orpheé aux enfers, Orpheus and Eurydice cannot stand each other; he’s a pretty insufferable violin teacher and she’s in love with the shepherd next door (the god Pluto in disguise). Orpheus and Pluto conspire to kill her so Pluto can have her, and Eurydice is actually rather happy to find herself dead in the underworld. Orpheus only attempts to rescue her because the character of Public Opinion threatens to ruin his career. While in the underworld, Eurydice is wooed by Jupiter in the guise of a fly, and they sing a hilariously strange love duet in which they wind up buzzing at each other like insects. Eurydice and Jupiter then attend a Bacchanale in Hades which begins fairly sedately but then explodes into the famous “galop infernale.” The audience would have recognized this music as a can-can, the music of long-legged chorus girls, high kicks, and frilly bloomers. Indeed, Parisian opéra-bouffe productions typically featured plenty of scantily-clad showgirls, but here Offenbach also plays that convention for laughs by making Olympian gods participate. Orpheus finally arrives with Public Opinion and the unhappy couple is resigned to be together yet again until Jupiter hits Orpheus in the rear end with a lightning bolt, causing him to turn around and lose Eurydice. She is delighted, especially when Jupiter transforms her into a priestess of Bacchus, and the operetta ends with a reprisal of the can-can.

“Offenbachian” operetta quickly spread to other regions of Europe, particularly Vienna and England. In Vienna its main proponent was the “Waltz King” Johann Strauss II (1825-99), whose farcical Die Fledermaus spoofed operatic conventions while also providing him with several more ballroom hits. In England, the team of librettist William S. Gilbert (1836-1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) became national heroes due to their string of successful operetti including H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance. Franz Lehár became the leading proponent of operetta in the 20th century and did much to cultivate and sustain the genre in its waning decades of popularity. His success with The Merry Widow injected a healthy dose of romantic sentimentality into the genre to counter-balance its tendency towards madcap comedy and satire.

As with perhaps any genre of music that is defined by its relation to another genre,the lines between operetta and opera sometimes become deliberately blurry. As noted earlier, one of the enduring qualities of Franz Lehár’s work (including The Merry Widow) is his desire to expand the craft of operetta beyond fairly stereotyped and formulaic music and plots and into more serious and lofty realms. This aspiration is not without potential pitfalls however. No matter the result, such ambition for improving one’s musical station inevitably risks accusations of snobbery. The traditionally light dance music of operetta also possibly conflicts with serious and meaningful plots, a mismatched juxtaposition perhaps made more obvious once Lehár began exploring newer 20th century styles like blues, foxtrot, and tango. However, Andrew Lamb contends that this conflict was resolved in Lehár’s last work Giuditta (1934), a five-act musikalische Komödie composed for the Vienna State Opera that allowed him to realize his musical aspirations. Still, the fact that Giuditta straddles the gap between operetta and opera has limited its acceptance in either repertoire. Ultimately, Lamb considers that although Lehár’s innovations and deviations perhaps undermined operetta’s distinct identity, the ascendance of new genres of light musical entertainment rooted in American popular styles truly signalled the end of operetta’s time in the limelight. By the mid-20th century, operetta’s traditional space in the world of popular musical entertainments was almost entirely taken over by the American musical on the one hand and sound film on the other.

© Ross Hagen