The Creators of Aìda

GIUSEPPE VERDI

As the composer, Verdi gets his own “Chapter,” and another one which lists all his operas and where and when they were first produced.

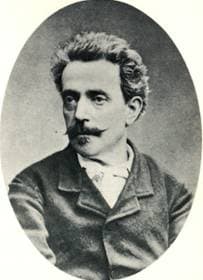

ANTONIO GHISLANZONI

In 1856, back in Milan, he published his first, and most successful, novel. Others followed, but he became better-known as the editor of La Gazetta Musicale and its off-shoot Rivista Minima, both published by Ricordi, who was Verdi’s publisher. In 1857 he wrote his first libretto, Le due fidanzate, a melodrama serio, with music by one A. Bauer, which must have been successful enough because Il conte di Leicester, a melodrama, (music also by the mysterious A. Bauer) was given the following year. Some sources tell us that over eighty librettos followed, though it seems the real number is closer to half that. But even forty in the last half of the nineteenth century is a remarkable output!

Now comes a quiz! 1): Who was Vladimir Kashperov? If you answered “Never heard of him,” I’d be right there with you! Obviously Russian, he lived in Italy from 1857 to 1865, where he composed two operas to Ghislanzoni librettos: Maria Tudor (1859), possibly based on the Schiller play which was the basis for Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda (one third of the “Three Queens” trilogy the Metropolitan Opera is producing this season for Sondra Radvanovsky) and Cola di Rienzi (1863), presumably based on Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1835 novel Rienzi: Last of the Roman Tribunes. Wagner’s Rienzi, by then two decades old, would have been unknown in Italy, since it wasn’t until 1871 that one of his operas – Lohengrin – was produced, in Bologna.

But, back to the quiz! 2): Antonio Carlos Gomes? He was a Brazilian composer sent to study in Italy. His Il Guarany was a huge success at La Scala in 1870 and established his reputation. Ghislanzoni subsequently wrote two librettos for him, but neither were particularly successful. 3): How about Giovanni Bottesini? But see below. 4): Some of you will recognize the name of Amilchare Ponchielli. He also set two Ghislanzoni librettos, one of which, I Lituani, was fairly successful and was even produced in Chicago and Toronto as recently as the 1980s. Ironically, his greatest success, La Gioconda, first performed in 1876, was adapted by Arrigo Boito (Verdi’s librettist for Otello and Falstaff) from the same Victor Hugo play which was the source of Ghislanzoni’s text for Gomes’s opera Fosca. A tangled web indeed! 5): How about Alfredo Catalani? La Wally holds a very tenuous place in the operatic repertoire; but, as we now can guess, G’s libretto for him preceded that success.

The Fates were not kind to Antonio Ghislanzoni. He was, according to Grove’s Dictionary, “[a]fter Boito…the most important Italian librettist between 1860 and 1890.” It’s sad that most of the composers he wrote for were nonentities, and ironic that those who were relatively successful achieved their greatest successes without him.

And then along came Giuseppe Verdi.

Tito Ricordi proposed a production of La forza del destino at Milan’s La Scala for 1869, but the immediate problem was finding a librettist to make the changes that Verdi, after its Russian première (in November 1862) as well as after its Spanish one in Madrid the following year, considered necessary. Piave, the original librettist, had been incapacitated by a stroke. Ghislanzoni was proposed and Verdi approved. The major problem was the final scene which, both agreed, needed to be changed. Verdi sent his new librettist a prose version of what he wanted. Ghislanzoni provided the verses. For a production of Don Carlos (originally in French) in Naples in 1872, Ghislanzoni wrote the required new lines. So it was logical that Verdi would turn to him for Aïda.

Auguste Mariette.