The Barber of Seville Program Article by Michael CliveOpera buffa in Two Acts

Music by Gioachino Rossini (1792 — 1868)

Libretto by Cesare Sterbini (1784 — 1831)

Based upon the play Le Barbier de Séville by Pierre Beaumarchais (1732 — 1799)

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: a beautiful young girl and a good-looking young guy fall in love. But the girl is living under the care of a much older guardian who also has eyes for her…and for the money she stands to inherit when she marries. Unfortunately, the young girl can’t marry without her guardian’s consent; fortunately, her young suitor is also rich (though he’s disguised himself to conceal his wealth), and he knows just the man to help them thwart the old guardian’s intentions. That would be Figaro, the barber, jack-of-all-trades, and master manipulator who seems to be everywhere at once in the swinging city of Seville.

If this scenario has the resonance of a rom-com, it was no less familiar to the audience members in the premiere season of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia in Rome in 1816. Not only were all the characters well-established types recognizable from innumerable buffo-style operas; they were also known to the French theatergoers who attended the play that was the opera’s source, Beaumarchais’ Le Barbier de Séville thirty years earlier. After all, the Comédie-Française had stock characters that paralleled those of the Italian Commedia dell’arte.

Gioachino Rossini

The fact is, these characters know no season or country; you’ll recognize them if you’ve ever watched a romantic comedy on television or at the movies. In strictest opera buffa tradition, each role is identifiable by type in The Barber of Seville. We have our Colombina, in this case named Rosina — pert, attractive, wily, ready to do what it takes to get what she wants; Il Dottore, the doctor (Dr. Bartolo), who is Rosina’s guardian and is greedy, self-deluding, and too old for an ingenue; Rosina’s young suitor, who disguises himself as the typically bumbling soldier Il Capitano but is actually the dashing Count Almaviva; and the Brighella, the shrewd servant-cum-factotum, Figaro.

This form of operatic comedy reached its zenith in the 19th century, and was a staple of bel canto style. Rossini was the foremost composer of bel canto operas; in fact, he and his most prominent rivals in the form, Vincenzo Bellini and Gaetano Donizetti, were all born within seven years of each other (Rossini first, in 1792). Bel canto rules were strict for both composers and librettists: Solo arias and ensembles, which required beautiful melodies and opportunities for vocal display, had to be arrayed in the approved structure. In comic operas, the characters hewed close to the archetypes handed down through generations of commedia dell’arte tradition — the Dottores, Colombinas, Brighellas and the like. More serious operas required a high moral purpose and more individualized characters of noble birth or character, often based on figures in history, legend, or myth.

You’re probably familiar with the spectacularly ornamented vocal lines in these operas, with roulades and flourishes that sound all but impossible to sing. Almost two centuries after Rossini’s success in writing these operas, the American diva Beverly Sills — herself a notable Rosina — quipped that sopranos in such roles would be rich if they were paid by the note. The very phrase bel canto, which simply means “beautiful singing,” has become synonymous with these vocal pyrotechnics, and understandably so. They are thrilling to hear for their own sake, and technically difficult to master; the notes come thick and fast, and they must all be delineated with accuracy and without apparent strain, requiring a voice of extreme flexibility and phenomenal breath control.

Though Rossini also wrote many serious operas, including lengthy historical epics such as Semiramide and William Tell, his contemporary audiences clamored for his buffo comedies. To his chagrin, there was far less interest in his weightier music dramas, which required much more effort from both composer and listener. Rossini could toss off a comic opera in a matter of weeks, and over a period of approximately two decades produced an average of two per year, and in some years, as many as four. It was the success of these comedies that financed his luxurious retirement at age 40; a dedicated gourmand, he settled in Paris, where he was known in all the best restaurants. Operas like The Barber of Seville had made him the most famous composer in the world, even when he was no longer composing them.

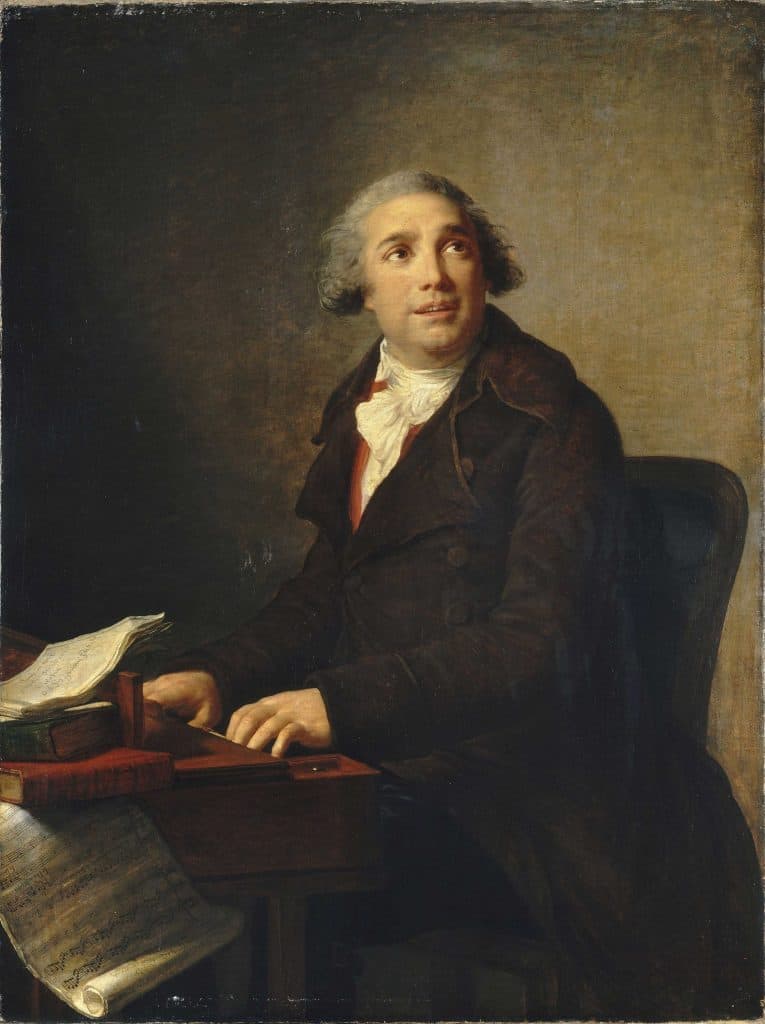

Paisiello at the clavichord, by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1791.

The premiere of The Barber of Seville, in Rome in 1806, was an unmitigated disaster. It was subverted by partisans of one of Rossini’s earlier rivals, the Rococo composer Giovanni Paisiello, whose 1782 version of the same Beaumarchais play had become wildly popular throughout Europe. After opening in Vienna in 1783, Paisiello’s Barber played simultaneously in five major theatres, making performances available in either German or Italian. But Rossini’s version soon eclipsed it, and today Paisiello’s work is rarely performed, while Rossini’s has only grown in popularity over the years. Today The Barber of Seville is recognized as one of the greatest of all musical comedies in Western theater, and is sometimes described as the ultimate opera buffa. How could it be otherwise with such delicious music and madcap comedy, irresistible and ageless? For those rare singers who are blessed with both comic acting ability and coloratura chops, Barber is a joy to perform, and we come away from the theater feeling that the cast has had as much fun onstage as we had watching and listening.

But there’s more to the success of this landmark comic opera. By taking Beaumarchais’ play as their source, Rossini and his librettist framed a politically provocative scenario within the confines of buffo tradition. Sterbini’s libretto is based on Le barbier de Séville, ou La précaution unutile (“The Barber of Seville, or the Useless Precaution”). The progressive ideas of the Enlightenment hide within plain sight in Barber — not just in the egalitarian sympathies in the text, but also in Rossini’s brilliant musical rendering of the Brighella, Figaro. He is a true workingman’s hero.

Finally, there is the Mozart connection: Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro is based on a later play by Beaumarchais, La folle journée, ou Le mariage de Figaro (“The Crazy Day, or The Marriage of Figaro”). Politically it is even more daring, with its explicit critique of the aristocracy; in Mozart’s rendering, its balance between psychological character study and slapstick comedy is more complex. The characters and setting are the same, but our Colombina and her dashing suitor, now the Count and Countess Almaviva, have been married for years and are having marital problems. To keep it all straight, just remember: Rossini, who came later, wrote the “prequel”; Mozart, who came earlier, wrote the “sequel”. Rossini, who venerated Mozart, had Figaro very much in mind when he depicted the characters in Figaro as their younger selves in Barber. And it’s likely he had Mozart’s masterpiece in mind when he expressed one of the greatest tributes any composer has ever offered another — calling Mozart “the inspiration of my youth, the despair of my maturity, and the consolation of my old age.”