Biography of Oscar Wilde

by Paul Dorgan

Young Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde was born in Ireland on October 16, 1854. His father, Sir Willliam, was a noted Ear-Nose-Throat surgeon; his mother’s nom de plume was Speranza and she hosted extravagant soirées in their Dublin home, No. 1, Merrion Square, probably the most fashionable address in the city. He was sent to Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, a town in the north-west of the country. (Many years later another great Irish writer, Samuel Beckett, would attend the school.) There, Oscar proved to be a brilliant student of Latin and Greek; the school awarded him a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin; from there he went in 1874, again on scholarship, to Magdalen College at Oxford University. There he perfected his pose, begun in Trinity, as the High Priest of Aestheticism. He also flirted, at times quite seriously, with converting to Catholicism. In 1878 he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry, and shortly after that he was awarded a rare “double first” – first class honors in Latin and Greek. In November he passed the Divinity examination and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree. He moved to London.

He wrote: essays, book reviews, poems; he applied for various positions, including some fellowships at Oxford, but was turned down. He was becoming famous though: “It’s extraordinary how soon one gets known in London.” Poems was published in both England and America in 1881; a play, Vera, was announced for performance in December of that year; while in April the latest opera by Gilbert and Sullivan opened. Patience concerns two poets rivaling for the love of the dairy-maid of the title; along the way, Gilbert has great fun with the Aesthetic movement. No wonder Wilde could, that year, say to a friend: “I should never have believed, had I not experienced it, how easy it is to become the most prominent figure in society.” As it turned out, Vera was cancelled when certain authorities, including perhaps the Russian government, realized that Life (the recent assassination of Czar Alexander II – not to mention that of America’s President Garfield) was far too closely imitating Art (the play deals with a plot to assassinate a Czar in 1800).

Patience opened in New York in September, 1881, and was proving to be a great success there. Richard D’Oyly Carte not only ran the company presenting the opera on both sides of the pond, but also arranged lecture tours. What better publicity could there be for his American production than to invite the High Priest of Aestheticism to give a series of lectures; American presenters wanted him to explain “The Beautiful.” Wilde arrived in New York on January 2, 1882, answering the customs officer’s question: “I have nothing to declare except my genius.” The press hounded him and kept their London colleagues informed of his progress. His first lecture, a week later, was, of course, sold out to the tune of $1211.00. He wore the costume of the Oxford Masonic Apollo Lodge, which immediately grabbed his audience’s attention by its oddity: they had no idea of its origin. To Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Baltimore and Boston, dropping, along the way, his Apollo Lodge attire. Then came a grueling schedule that took him all over the country (Salt Lake City, April 11) finally returning to New York City in October 1882.Two months later he sailed for England.

Oscar Wilde

In January he decamped for Paris where he met writers and painters, finished his 5-act, blank-verse The Duchess of Padua and revised Vera; he also renewed his friendship with the great Sarah Bernhardt. In May he was back in London and began his courtship of Constance Lloyd. In need of money, he embarked on a lecture-tour of the British Isles. In August he returned to New York for the première of Vera. It was not a success, even on tour, and Wilde returned to lecturing the Isles. By November he was engaged and in May 1884 married Constance; the honeymoon was spent in Paris. Another lecture tour began in October, but audiences, uninterested in “Dress,” stayed away in droves and the tour ground to a halt the following March. He turned to journalism, writing essays and book- and theatre-reviews. His first son was born in June 1885; his second in November 1886.

It was during his wife’s second pregnancy that Wilde began an affair with a much younger man, the first of a series with younger men who drifted in and out of his life, culminating in the disastrous relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas.

Reviews continued to be written, drawing admiration from his fellow-countryman, George Bernard Shaw. In 1887 he became editor of a monthly journal, The Woman’s World, but tolerated the job for less than two years. Inventing stories for his young sons possibly piqued Wilde’s interest in the short story as a literary form. The publication of The Happy Prince and Other Tales in 1888 brought him comparisons to Hans Christian Andersen. The following year , “The Portrait of Mr. W.H.” appeared in one of London’s literary journals. In 1890 another of the London journals published Wilde’s longest piece of fiction, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which repelled some reviewers by what they saw as its “immorality.” Wilde, delighted with the publicity the book was receiving, would have none of the negative criticism, and wrote letters to the papers defending his novella; he concluded one letter: “…leave my book, I beg you, to the immortality that it deserves.” Now there’s the Oscar we all know and love! Another volume of stories, these ones mysteries, came out in 1891: Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime and Other Stories.

In January, 1891, Guido Ferranti opened in New York. It was The Duchess of Padua retitled and revised, and it lasted three months. London theatre managers were uninterested in it. One of them, though, did offer an advance on a “modern” play; Wilde was reluctant, but by October the script was written. Lady Windermere’s Fan opened in February 1892 to rapturous applause from the audience, and the chilly critical response did not deter the public from flocking to the theatre.

In the months before LWF went into rehearsal, Wilde was in Paris, meeting old friends and making new ones. Much of the conversation concerned the portrayal of Salome in print and on canvas. For details on this visit, the resulting play and its production travails, see the chapter “Oscar Wilde’s Salome.”

In October of 1892 a new script was ready, began rehearsals in March and opened in April. The actors were applauded, Wilde was booed, the critics were more favorable, and A Woman of No Importance settled in for a steady run.

It was while Wilde was working that summer on his latest play that his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas began. “Bosie” was the third son of the Marquess of Queensbury (who, in his young days, drew up new rules for boxing and persuaded both England and America to adopt them – the so-called “Queensbury Rules”); it was a volatile relationship, for the young man was prone to violent outbursts of temper, perhaps inherited from his father. They both claimed to love each other, and perhaps they did. Douglas knew the seamier side of gay life in London and introduced Wilde to the world of rent-boys, which opened him up, on at least one occasion, to blackmail. Increasingly, Wilde walked a very narrow line with respectability on one side and disgrace on the other.

In the summer of 1893, Oscar started on a new play, An Ideal Husband, and there was the matter of translating Salome for its English edition – he had written it in French. Having refused to sit his Final Exams in Oxford, Bosie was aimless and, in his lover’s words, “nervous and rather hysterical.” In an effort to have him do something, Wilde commissioned him to write the translation. The result was a disaster and a huge row between the two. The conflict was eventually resolved when it was decided that Wilde’s name alone would appear on the title page, and the play would be dedicated to Douglas.

In August/September The Importance of Being Earnest was written; Husband went into rehearsals in December, and the opening in January was another triumph. A month later, Earnest was given its première. Among the generally rapturous reviews only Bernard Shaw, who had enjoyed IH, expressed disapproval: he reckoned it must have been written at least ten years earlier. “It amused me, of course; but unless comedy touches me as well as amuses me, it leaves me with a sense of having wasted my evening.”

The Importance of Being Earnest

Oscar Wilde’s professional life seemed at its zenith, but his personal life was moving, inexorably, to its tragic nadir. Matters between Queensbury and his son had been simmering throughout 1894. In October the Marquess’s eldest son and heir died supposedly in a shooting accident; many considered it a suicide as he was reputed to be involved with the Foreign Minister, Lord Roseberry, and feared exposure from blackmail. Queensbury was determined that his family would not suffer another tragedy for the same reason. It was rumored that he planned to disrupt the first night of Earnest (on February 14, 1895), so his ticket was cancelled and a policeman positioned at the theatre. Four days later he left his card, on which he had written ‘To Oscar Wilde posing Somdomite’ at Wilde’s club. Despite the advice of friends (one of whom had written saying he should realize he was merely a pawn in this father-son conflict and would be destroyed by one or the other), Wilde decided to prosecute for libel, even after Queensbury’s friends, including Shaw, told Wilde he would lose the case. But Douglas taunted him as a coward if he backed down.

The trial for libel began on April 3, 1895, and ended two days later when Wilde withdrew from the case and Queensbury was, therefore, acquitted. This, though, left Wilde open to prosecution on charges of “gross indecency,” under the recently-passed Criminal Law Amendment Act. Fully aware of that probability, especially since the judge was asked to authorize a warrant for Wilde’s arrest, the court was adjourned at 3.30 pm for an hour and a half to give Oscar time to catch the last train to Dover and thence to France. Wilde, in his London hotel, seemed paralyzed: “I shall stay and do my sentence whatever it is.” Shortly after six he was arrested “on a charge of committing indecent acts.”

Initially Wilde was held at Bow Street Magistrate’s Court but was later transferred to Holloway Prison. There was a hearing on April 6, a second on April 11 and a third on April 18. The criminal trial proper opened at the Old Bailey on April 26, 1895. He and an accomplice were charged with twenty-five counts of gross indecencies and with conspiracy to commit gross indecencies; the conspiracy charges were eventually dropped. The trial ended on May 1. The jury deliberated for about three hours but could not reach a verdict. A new trial was ordered. Bail was eventually granted a week later and Wilde left prison for the three weeks before his next trial began.

Many, including Queensbury’s attorney in the libel case, felt that the second trial should not take place, that Wilde should leave the country so a second trial could not take place, and that the whole sordid business should be allowed to fade from public consciousness. The Solicitor-General was importuned not to let the trial proceed; he seemed to favor that idea “but for the abominable rumors against Roseberry.” Lord Roseberry was the current Prime Minister and we will remember that, as Foreign Minister, he was suspected of an affair with his secretary, Viscount Drumlanrig, who, fearing exposure from blackmail, committed suicide. Drumlanrig was heir to the Marquess of Queensbury and thus Douglas’s eldest brother. A web of tragic family intrigues worthy of Ancient Greek Tragedy!

The second criminal trial began on May 20; it lasted less than a week. Frank Lockwood, the Solicitor-General, led the prosecution, which pretty much echoed that of the earlier one, except that the weaker witnesses were dropped. Again the jury deliberated for about three hours; this time their verdict was guilty on all counts. Mr. Justice Wills sentenced Wilde to “be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for two years.”

With the start of legal proceedings, An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest became anonymous plays, but the London public registered its disapproval by staying away, and both plays closed. A planned American tour of A Woman of No Importance was cancelled. Sadder than the cancellation of these various productions (with the loss of royalties) was his abandonment by friends, both English and French.

Constance Wilde

What of Constance Wilde during all of this? Once her two boys were of an age when a Governess could look after them, she began to prove herself to be not the typical Victorian, stay-at-home wifeandmother! She began to participate in various political activities; she also published two collections of children’s stories, which were well-received by the critics, and contributed articles to Woman’s World. After the affair with Douglas began, Oscar was seldom home, though she often begged him to return. When told that the libel case went against her husband, she hoped that he would go abroad, and between the two criminal trials she visited him and begged him to leave the country. She was urged to start divorce proceedings when her husband was imprisoned, but he told his brother-in-law that he could not bear the inevitable separation from his children and his wife. She wrote to tell him she would drop the proceedings and also wrote to the prison governor asking to see her husband. The visit horrified Constance: she could not see him, nor touch him, but she agreed to allow him to rejoin her and the boys on his release. In February 1896, having changed her name to Holland, she travelled from Italy to tell her husband of his mother’s death; they spoke of their children and of the future, but , again, the visit affected her deeply: “…he is an absolute wreck.” She saw her husband for the last time in February 1897. After his release and his settling in France, she wrote weekly letters that spoke of plans to bring the boys to see him, but she never mentioned her own health. Some years earlier in her London home she had injured her spine in a fall; now, it seemed, a second surgery would be required, which took place in early April 1898. She died a few days later.

After sentencing, Wilde was brought first to Newgate prison where the warrant authorizing his sentence was drawn up, after which he was taken to Holloway in the north of London. In June he was moved to Pentonville; the next month, thanks to the intervention of Richard Haldane, a friend who was a member of a government committee investigating prisons, he was transferred to Wandsworth Prison in south-west London. The sentence of “hard labour” did not merely apply to the physical work required, but to the plank bed (without a mattress); the wretched diet; the one hour of open-air walking, in single-file and in silence, with the others in his block; the initial lack of communication with those outside and subsequent allowance of one letter out and one in; the 20-minute visits by three friends, separated by wire blinds and under the watchful eye of a warder. Soon he was insomniac, and his constant hunger (because his stomach couldn’t tolerate the prison diet) was exacerbated by the dysentery he developed. And let’s not even go into the sanitary arrangements at the prison!

Once he fainted in chapel (a daily requirement – chapel, not fainting!), a fall which damaged his right ear. This, combined with his dysentery, necessitated a two-month stay in the infirmary. Hearing of this, Haldane arranged in November 1895, for Wilde to be transferred to the prison at Reading, a city about an hour’s train-ride north-west of London. It was obvious that “hard labour” was out of the question, so Wilde was assigned to work in the garden and take charge of the library; he was allowed to read in his cell, but letters were still restricted.

Reading Gaol was certainly a more congenial place than Wilde’s previous prisons, but the physical and mental results of the conditions imposed on him by the Governor were enough to alarm his friends. More books, permission for more letters, both written and received, and, most importantly, a new warden, were sent to Reading Gaol. Perhaps the most profound result of this relaxation was the long letter to Douglas, written over the first three months of 1897, and eventually called De Profundis (The title refers to one of the psalms: “Out of the depths, I cry to you.”). On his release, Wilde had two copies made, one for Bosie and one for himself. Not until 1905 was part of it published; the complete text had to await publication until 1962.

Reading Gaol

On May 18, 1897, he left Reading Gaol for Pentonville in London, from where, the next day, he was discharged, having completed his two-year sentence. That afternoon he took a train to Newhaven and the night boat to Dieppe in France. He was now Sebastian Melmoth. Scarcely settled in his hotel, a letter arrived from Bosie. Douglas, on the advice of his lawyers, had left England before Wilde’s first criminal trial. He had written many letters, but they had been ignored; he had written articles for French journals about his relationship with Wilde, but Oscar had refused to allow his letters to be quoted in them. Wilde’s prison time gave him ample opportunity to meditate on how his younger lover had used and abused him, so he was in no mood to renew the relationship.

In Dieppe, Wilde had plans for plays, which came to naught. In July he began The Ballad of Reading Gaol; he revised it in August. He moved to nearby Berneval, where he thought he might be anonymous enough to elude publicity and Queensbury’s detectives. That proved impossible. Old friends visited, as did new ones. London theatre managers wanted new plays. Bosie bombarded him with letters about needing to see him again, but Constance had stipulated that her allowance would end if he and Bosie met again, and Daddy Queensland had made it very clear that he’d shoot them both! Ignoring the threats they met, briefly, in August 1897. In September Oscar moved to Paris and then set off for Naples with Bosie. English society there was not happy. Neither was Constance when she heard of it and stopped his weekly allowance. Neither was Douglas’s mother who threatened to stop his allowance. Bosie left Naples, and Wilde, on December 3.

Oscar stayed on until February; he returned to Paris to await the publication of The Ballad of Reading Gaol. The initial printing in January was four hundred copies; soon another four hundred were printed and, at the end of February, another thousand. By May the volume had been reprinted six times. With the seventh printing, in May of 1899, the real name of the author was revealed: up to then the name on the title page was “C.3.3” – his Reading Prison identification number. Reviews recognized that a “literary event” (whatever that might mean) had happened, but not all were unanimous in their praise. W.B. Yeats, including it in his 1936 edition of The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, called it an “almost-great poem”, and had felt no compunction about cutting stanzas he felt were inferior! Friends hoped that the success of the poem would reignite Wilde’s desire to write. His last two plays were readied for publication and he set about correcting the proofs: “I can write,” he told a friend, “but have lost the joy of writing.”

Wilde’s last years were lonely ones. Sometimes friends took him away from Paris for extended periods of time. Sometimes acquaintances from his London life ran into him in the street and asked him to dinner. Sometimes they snubbed him. But he lived alone in a grubby hotel and was always broke. One day, the story goes, he saw the great Australian diva, Dame Nellie Melba, on the street; he approached her, reintroduced himself (they had met during his London life) and asked for money. Bless her! For she gave him whatever money she had in her purse.

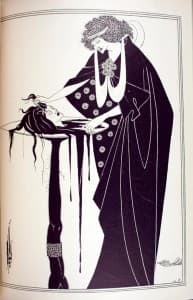

Beardsley Salome Illustration

Family and friends were dying: his wife Constance died in 1898; Aubrey Beardsley, the illustrator for the English edition of Salome, died that same year, aged only twenty-five; his brother Willie in 1899; one of his faithful friends (after his release from prison there may have been five or six) in 1900. His nemesis, the Marquess of Queensbury, died at the end of January 1900. The Marquess had not had a happy time of it after the trials, though it is to his credit that he encouraged Wilde to leave England after the first criminal trial. With his death, Lord Alfred Douglas, “Bosie,” inherited a tidy ₤20,000! (I’ve no idea what that converts to today, but it must be some millions of dollars). Wilde was encouraged to ask his former lover to settle some of that inheritance on him: after all, in the good days, Wilde had, essentially, subsidized him. Bosie flew into a rage and refused.

In addition to the emotional pain and embarrassment of the rejection and snubbing by friends, these years were also painful ones, for his health began to decline. There was a nasty rash which itched. In October, 1900, his right ear (the one that was damaged when he fainted in the prison chapel) was operated on, but he developed an abscess which developed into meningitis. Two old friends shared the nursing of him. By the end of November he could no longer speak. Throughout his life Wilde had many times spoken of converting to Catholicism. Now one of the friends sent for a priest who blessed him and gave him the Sacrament of the Dead. Neither his friends nor the priest knew if Oscar was conscious enough to know what was happening. Wilde’s death certificate noted the time of death as 2.00pm, November 30. He was buried at the Bagneux Cemetery in Paris on December 3. In 1909 his remains were removed to the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

WILDE WORKS.

Plays.

Vera, or The Nihilists 1880. Revised in 1883

The Duchess of Padua 1883. Revised, 1891, as Guido Ferranti

Salome 1891.

Lady Windermere’s Fan 1892.

A Woman of No Importance 1893

La Sainte Courtisane 1894. Unfinished.

An Ideal Husband 1895.

The Importance of Being Earnest 1895.

Stories.

The Happy Prince and Other Tales 1888.

The Picture of Dorian Gray 1890.

Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime and Other Stories 1891.

Poems.

There are over 80, but the best of them is The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Prose.

De Profundis In January 1897, Wilde, at the instigation of the Reading Prison Warder began a letter to Lord Douglas, his former lover whose father had brought about Wilde’s imprisonment and disgrace. The letter was never sent, but, in 1905, Robert Ross, one of Wilde’s friends, published a censored version. The complete text did not appear until 1962.