Politics, Race, Gender, Sex, and Religion in Abduction

by Luke Howard

For such a young composer relatively inexperienced with opera, Mozart certainly didn’t shy away from tackling some thorny political and social issues in Abduction from the Seraglio. The light-hearted nature of the Singspiel genre itself helped him, as would the comedic element of opera buffa when he soft-pedaled the politics in his later operas like The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni. It’s easier to raise difficult questions with humor. But with Abduction, the hot-button social issues are very much apparent—they actually drive the plot and the drama from the start.

Most apparent is the contrast between Christian and Moslem cultures. We should remember, of course, that the portrayal of 17th-century Turkish Islam in Abduction is filtered through 18th-century Christian sensibilities. These portrayals reflect merely the way the Viennese tended to think of Islam, not how it actually was! Neither is the juxtaposition between religions presented in black-and-white terms, reflecting perhaps the growing Enlightenment mistrust of Christianity (expressed through the writings of Voltaire) and in the goal of finding nobility in other societies and cultures (as outlined by Rousseau’s philosophy of the “noble savage”).

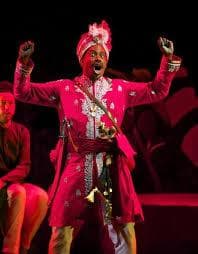

Osmin

While the character of Osmin might be intended to represent the threatening and violent aspect of the exotic “other,” he is also clearly a caricature. And neither is the Pasha an accurate representative of Islamic thought and practices, having been converted to Islam only a few years earlier after being forced out of Christian Spain. Though they both threaten their slaves with torture, and seem to relish the sexual licentiousness of the seraglio or harem, it is the Pasha who acts with true nobility and forgiveness in the end. But does the Pasha’s change of heart happen because of his new-found faith in Islam, or is it a remnant of Christian charity? Or neither? Mozart seems to present the religious differences as important plot devices without judging either religion.

The Christianity of the European characters—Belmonte, Konstanze, Pedrillo, and Blonde—is more assumed than stated. But as they represent their culture to the Turks, and as they act out their plans, their behavior is marked by mockery, deceit, fraud, cowardice, bribery, misrepresentation, and any number of devious character traits. Of course, it’s not Mozart’s intention to use this work as a vehicle for expressing the highest aspirations of a Christian society. But in the contrast between West and East in Abduction, neither culture comes out looking squeaky-clean. Only the Pasha and Konstanze act with resolute integrity throughout the opera, and that integrity is concerned more with the quality of love than it is with their respective faiths.

Osmin and Pedrillo

The question of commitment to religious principles arises periodically throughout the opera, but no more explicitly than when Pedrillo tried to induce Osmin to drink wine in Act II. Pedrillo says that the prophet Muhammad’s prohibition on alcohol is one of the “stupid laws” of Islam, and manages to tempt Osmin to flout his own religious beliefs. Certainly Pedrillo believes that the end—freedom from the seraglio—justifies the means, and a “brotherhood” forms between the two men based on their shared love of wine. It’s a duplicitous, manipulative “brotherhood,” of course. Osmin doesn’t just feel aggrieved in Act III, he actually has very good reasons to want to punish the Spaniards who have tricked and deceived him repeatedly.

It’s tempting to see this “brotherhood of the bottle” as emerging again several decades later in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The music for the famous “Ode to Joy” in the final movement of that symphony is very clearly modeled on the simple and familiar traits of a German drinking song. Beethoven’s idea of universal brotherhood seems to have centered on an image of everyone gathering together in conviviality and sharing a few rounds of beer with each other at the local bar. Then, after a number of variations, the “Ode to Joy” theme returns in its “Turkish March” incarnation. Beethoven says here to his 1820s Viennese audience that this “universal brotherhood” can unite the Viennese with their former enemies from Turkey if everyone would just sit down and share a drink. (President Obama’s 2009 “Beer Summit” was not such an original idea after all—it might have had its origins in Mozart’s opera!)

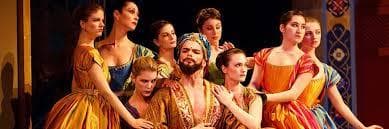

Harem

Related to the red flags of religion and race is the setting itself in a Turkish harem. If the Pasha was once a devout Christian who has converted to Islam, then he certainly seems to have taken on board the sexual liberty of a harem without too much crisis of conscience. Though he loves Konstanze, and tries to win her heart, the audience is perfectly aware that he has Turkish women waiting for him behind the scenes. It is by juxtaposing the resistance of Blonde and Konstanze with the (presumed) acquiescence of the rest of the harem that much of the cultural/religious/sexual conflict is played out in the opera. Even at the end of Act II, the plan to rescue Blonde and Konstanze almost comes undone because the European men insist on faithfulness and sexual purity—concepts that are almost rendered moot within the culture of the harem.

Mozart also has some fun with this topic, lightening somewhat the potential tension. The character of Osmin, the head of the harem, is almost certainly a eunuch. And while Osmin’s sexual frustrations are an important plot device in Abduction, the decision to make him a basso profundo (with a low D, below bass clef) is one of Mozart’s more delightful ironic touches. Casting him as an actual castrato wasn’t really an option—the castrati were prominent in Italian opera, not German Singspiele, and were heroic instead of comic. But with two tenors already in lead roles, somebody had to be a bass, so Mozart decided it should be the eunuch. But the fact that he had a famous basso profundo—Ludwig Fischer—already assigned to sing in this opera was probably more of an inducement to make Osmin a bass than the irony of a low-voiced eunuch.

Scholars still argue today about whether Mozart’s Osmin is a eunuch or merely the Pasha’s general, but the Osmin character and name were common in 18th-century stories, both pre- and post-dating Abduction, where he was unquestionably a eunuch. Considering the popularity of Montesquieu’s Persian Letters, which were widely read in the 18th century, it’s likely that Mozart’s audiences assumed Osmin was a eunuch. It was probably also assumed that he was black, of African origin.

Intertwined with the questions of religion and sex are, of course, issues of gender: the contrast of Turkish women with European women, the differences in thought patterns and expectations between European men and women, the cross-cultural gender battle as two male Moslems pursue the love of two European females. Blonde outlines to Osmin the manners by which an English woman might be won (manners that are, of course, the opposite of Osmin’s expectations) in her Act II aria “Durch Zärtlichkeit.”

But that she does so while being coy and flirtatious with Osmin indicates that she is willing to play gender games, and though she is more feisty than the others, is also more willing than Konstanze to give herself up to the situation in which she finds herself.

Old World politics play into this story, especially in Act III. When Belmonte informs Pasha Selim that his father is Lostados, Governor of Oran, he invokes Western notions of the nobility of great families, along with particulars of Mediterranean regional governance. It’s clear from Selim’s response that the nobility weren’t always so noble in their actions—Selim calls Belmonte’s father a “barbarian.” But the city of Oran, even though incidental to this story, is incredibly important in understanding Spanish relations with the Ottoman Empire. Oran is a major city on the Mediterranean cost of Algeria. It was founded by Moorish traders, captured by the Spanish in 1509, but then conquered by the Ottomans in 1708. Spain recaptured the city in 1732, but King Charles sold it to the Turks in 1792, only ten years after Abduction premiered. Even into the 20thcentury, it was the most Europeanized city in North Africa. So while Belmonte, Konstanze, and Pedrillo are culturally Spanish—the story is set in the 17th century when Oran was under Spanish rule—they hail from one of the most hotly contested trading cities in a centuries-old Spanish-Turkish rivalry. Thus, the practices of Islam were perhaps not so foreign to these characters as they would seem to the audience. Even the decision to have Belmonte pretend to be an architect in the Pasha’s service puts him in the position of a Janissary—it was from the corps of Christian Janissaries that Ottoman rulers typically educated and chose their architects and engineers. Indeed, Blonde’s “Englishness,” and her insistence on gender rights, freedom, and independence of thought, are among the more “exotic” traits in this opera from the viewpoint of the rest of the cast of characters. Blonde, the Englishwoman, stands out as culturally distinct from the rest, who are all more-or-less blended Spanish/Turks.

Ludwig Fischer

Even the opera’s conclusion has an ironic political slant to it. The final quartet sing together, “To be generous, merciful, kind, and to forgive selflessly, is the mark of a noble soul.” And Pasha Selim himself proclaims, “It’s a far greater pleasure to avenge injustice with good deeds than it is to repay crimes with crimes.” And yet, the violence of the French Revolution, where forgiveness, mercy, and generosity were in short supply, was less than a decade away when Abduction from the Seraglio premiered in 1782.

Dr. Howard began his formal music studies in Sydney, Australia, where he received the Bachelor of Music Education degree with an emphasis in piano. He then earned a Master of Arts in Musicology from BYU in 1994, and a Ph.D. in Musicology from the University of Michigan in 1997. Dr. Howard has previously served on the music faculties at Minnesota State University Moorhead and the University of Missouri Kansas City. In 2002, he joined the faculty of the School of Music at Brigham Young University where he teaches music history and Western cultural history.