The Singspiel and Mozart

by Dr. Luke Howard

Few composers have exerted such a pronounced impact on the development of opera as Mozart. Like his older colleague Christoph Gluck (1714-87), Mozart understood that the mid-18th century traditions of opera inherited from the baroque had become stale and stilted. By applying many of Gluck’s suggestions for operatic reform—more dramatic integrity, less artifice, and greater connection between music and drama—Mozart created a vibrant and rich tradition of his own that has not diminished either in importance or influence in subsequent eras.

Mozart

While Mozart excelled at composing Italian opera, both comic and serious, he also periodically dabbled in the German-language genre of the Singspiel, in which spoken dialog is interspersed with set musical numbers (much like a Broadway show). The Singspiel tradition as a form of popular entertainment was less set in its ways, less formal, and therefore in less obvious need of reform and innovation. When Mozart composed Singspiele, as he did throughout his career, he felt freer to indulge in the whimsy, wit, and populist musical styles associated with that genre than he did in his Italian operas. Even though he spoke fluent Italian, Mozart also had the advantage of working in his native language with the Singpsiel, which also broadened its reach to the German-speaking audiences in Vienna.

As a genre, the Singspiel had its origins in the semi-sacred miracle plays of medieval Germany. It was only in the 17th century that secularized Singspiele began to appear, making the genre as Mozart knew it actually a more recent development than Italian opera. It was still relatively fresh and ripe for expansion. Mozart’s first “opera” in any form was actually part of a sacred Singspiel which he composed in 1767 when he was only eleven years old, titled Die Schuldigkeit der ersten Gebots (“The Obligation of the First Commandment”). Mozart wrote the first part of this work, with Michael Haydn and Anton Adlgasser contributing the other two parts. The whole work was performed in the palace of the Archbishop of Salzburg (which, coincidentally, would become Mozart’s place of employment six years later).

The mid-18th century Singspiel was, however, more usually a popular form of secular entertainment, produced by travelling troupes more frequently than by established opera companies. It was during this period that the young Mozart was lapping up as many different musical experiences as he could.

Just as the Singspiel was really hitting its stride as a popular entertainment in Austria, Mozart wrote his first secular work in the genre, the comedy Bastien und Bastienne. This work was commissioned when Mozart was only 12 years old, but already the young genius composer showed a mastery of both French and German vocal forms. A parody of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s French opera Le Devin du village, Bastien und Bastienne was a small-scale, one-act comedy that was almost certainly intended to be a somewhat portable entertainment. One contemporary report mentions that it was premiered in the garden theater of the patron who commissioned the work, Dr. Franz Mesmer, which would partly explain the small scale of the work. Though an example of Mozart’s juvenilia, Bastien und Bastienne, gave the composer crucial experience in music for the stage, which admittedly seems to have come to him naturally anyway.

Through his teen years, Mozart wrote numerous serious operas, and occasionally ventured again into German-language stage music. In 1774, he wrote incidental music in an operatic style for a production of the German play Thamos: König in Ägypten, which was later expanded in 1779 with extra choruses and interludes. In 1779, Mozart also started work on a new Singpiel titled Zaide. He never completed the work, and none of it was performed (that we know of) during his lifetime.

One of the motivations for Mozart to work again in the German genre might have been the establishment of the Nationalsingspeil, a theatrical project sponsored by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, with the specific goal of encouraging German-language opera in Austria. Zaidemight have functioned as something of a trial run for Mozart, re-acquainting himself with the genre of the Singspiel that he had only sporadically experimented with in the past. Unhappy with his position working for the Archbishop of Salzburg, he actively sought opportunities for success in arenas that might offer respite from a restricted employ in what he considered a provincial town, and the Emperor’s new theater project provided such an opportunity. In the meantime, Mozart had enjoyed great success in Munich in early 1781 with Idomeneo, an Italian opera seria.

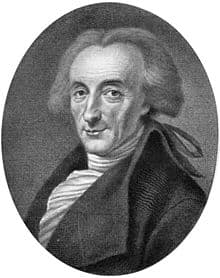

Joseph-II

Flush with the success of Idomeneo, Mozart left Salzburg for Vienna, bringing with him the score for Zaide which he showed to Gottlieb Stephanie, the director of the Nationalsingspiel. Stephanie was impressed with Mozart’s score. What’s more, the theater manager, Count Orsini-Rosenberg, had heard Mozart play through some excerpts of Idomeneo, and was also struck by Mozart’s skill as a composer of staged musical drama. With the Count’s support, Stephanie agreed to commission a new Singspiel from Mozart, and he set about finding a suitable libretto himself.

Stephanie seems to have taken the easy road to finding a libretto—he simply pirated a libretto by Christoph Bretzner from a Singspiel produced in Berlin that same year (1781) titled Belmonte und Costanze, oder Die Entführung aus dem Serail. The music for this production was by Johann André, whose son (Johann Anton André) would later intersect with Mozart’s music rather dramatically. In 1799, Johan Anton André purchased amajor collection of hundreds of Mozart’s manuscripts from Mozart’s widow, Constanze, and started publishing them in highly-respected editions, many of the works appearing in print for the first time. He is sometimes, therefore, referred to as the “father of Mozart research,” but for the time being, the most significant connection between Mozart and the Andrés was that Mozart was about to set the same story to music that Johann André had set in Berlin earlier that year.

Idomeneo

Gottlieb Stephanie

Johann Andre

Stephanie tweaked the libretto a little here and there, but it was still the same story, with the same characters and basic plot outline. What made this story take off in Vienna, though, in a way that it didn’t in Berlin was not only the quality of Mozart’s music. It was the Viennese fascination with exoticism in general, and the Ottoman Empire specifically.