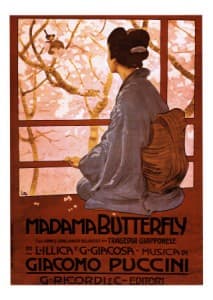

The Making of Madame Butterfly – Part Three. The Libretto.

by Paul Dorgan

NOTE: The Writer assumes the Reader has read the other “chapters”; if Reader hasn’t, Writer respectfully requests Reader so to do, if only to be clear about the non-operatic people, and their works mentioned below. Apart from that, they’re well-written, informative, and – oops: Writer shouldn’t brag!

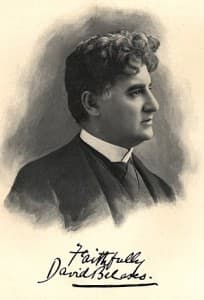

With an opera successfully launched in Italy and in demand elsewhere, Giacomo Puccini liked to “supervise” productions in major cities, all the while sniffing around for his next subject. Thus he was in London in the summer of 1900 for the Covent Garden première of his latest opera, Tosca. On a free evening during his six-week stay, he went to the Duke of York’s Theatre, where a pair of one-act plays was playing: Jerome K. Jerome’s Miss Hobbs, and David Belasco’s Madame Butterfly. The transfer from Broadway to London of David Belasco’s stage-adaptation of John Luther Long’s story profoundly affected the Italian composer, especially the so-called “Vigil Scene,” where Butterfly, Suzuki and Trouble wait for Pinkerton’s return to his house: the transition from evening, to night, to dawn, and to full morning, was a demonstration of Belasco’s genius in taking advantage of the relatively-new-fangled thing known as “electric light.”

With an opera successfully launched in Italy and in demand elsewhere, Giacomo Puccini liked to “supervise” productions in major cities, all the while sniffing around for his next subject. Thus he was in London in the summer of 1900 for the Covent Garden première of his latest opera, Tosca. On a free evening during his six-week stay, he went to the Duke of York’s Theatre, where a pair of one-act plays was playing: Jerome K. Jerome’s Miss Hobbs, and David Belasco’s Madame Butterfly. The transfer from Broadway to London of David Belasco’s stage-adaptation of John Luther Long’s story profoundly affected the Italian composer, especially the so-called “Vigil Scene,” where Butterfly, Suzuki and Trouble wait for Pinkerton’s return to his house: the transition from evening, to night, to dawn, and to full morning, was a demonstration of Belasco’s genius in taking advantage of the relatively-new-fangled thing known as “electric light.”

Belasco, years later, said that Puccini came to his dressing-room after the performance, asking for the performance rights. The author/director agreed at once. Question 1: Why would the director/author have his own dressing-room? Question 2: Why would an American director/author hang around in London after his play was successfully launched? Methinks Belasco, with Madama Butterfly hugely successful in every Opera House, was trying to lay claim to a small ownership of Puccini’s opera.

The composer initially liked the play because it presented a conflict between the values and the cultures of America and Japan; he was impressed by the visual effect of the “Vigil Scene” ; and he loved Butterfly’s suicide at the end. He did write to a friend, though, that the play was “very beautiful but not for Italy.” Despite Belasco’s memories, Puccini was not averse, on his journey home, to wondering in Paris if the rights to Émile Zola’s latest, sensational novel, La faute de l’Abbé Mouret, were available: they had been promised to Jules Massenet, the composer of Manon and Werther. Disappointed, he noted he had returned from London “an unemployed opera composer,” but he did ask Ricordi to investigate the possibility of obtaining the rights to Madame Butterfly. And there were discussions with Illica about a libretto based on the doomed Marie Antoinette; a possible adaptation of Victor Hugo’s vast novel Les Misérables, or maybe Edmond Rostand’s play Cyrano de Bergerac. Puccini became more and more attracted to the Belasco one-acter: “I think that instead of one act I could make two quite long ones: the first in North America, the second in Japan…”

The greatest difference between this first draft and the opera we know today is in the relationship between the American sailor Pinkerton and the American Consul Sharpless. Our Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton was, in that draft, called Sir Francis Blummy Pinkerton! Long’s story mentions “Mr. B. F. Pikkerton.” Maybe Illica thought “Sir” (as in “Yes, sir”) was a polite form of “Mr” instead of the result of a British monarch conferring a knighthood (as in SIR Ian McKellan); “Francis” is an acceptable first name, but where did “Blummy” come from? Illica’s vague memory of the English exclamation “Blimey!”?

The draft-Sharpless seems younger than the Consul we now know; he approves of Pinkerton’s sexual predatoriness, and is amused by the “comedy” of the younger man’s marriage in the “Japanese” manner; Pinkerton considers it simply a business arrangement: he could never take a Japanese “bride” seriously as a woman or a wife. Together they mock the “smallness” the Japanese admire, and both think absurd the Japanese tradition of naming people after flowers or insects. In his aria Pinkerton uses many English words in describing how the “Yankee” conquers the world; the second verse, with its description of Butterfly, is nothing more than a list of the oriental stereotypes Loti gives us.

Having written the libretto for Mascagni’s 1898 opera Iris – a lurid (and not very successful) piece set in Japan – Illica must have felt himself eminently qualified, armed with translations of Long’s story and Loti’s novel, to provide Puccini with a libretto for Madama Butterfly. In April, 1901, he received news that Ricordi had been given the rights to Belasco’s play. Why pay Belasco, wondered Illica? Everything he needed for the libretto was in Long’s story! Ricordi, even with the rights to the play, was not convinced of the viability of the piece; and his doubts were not assuaged by a letter from Illica which questioned the role of Pinkerton: 1) he’s unsympathetic in Act 1; and, 2) he doesn’t reappear until the end of the opera, where he is even more unsympathetic. A new translation of Long’s story, commissioned by Puccini from an anonymous American woman, didn’t really change anything. In June, Puccini found an Italian version of Belasco’s script which he sent to Ricordi, who was finally convinced that it could work.

Illica initally considered a libretto in 2 acts: the first a Prologue, with the second divided into three scenes: Butterfly’s house; the Consulate; Butterfly’s house. Somewhere along the way that was altered to three acts: Butterfly’s House (Long’s story with lots of “local color” taken from Loti’s novel); The Consulate (Long’s story); Butterfly’s House (Belasco’s stage adaptation of Long). Illica, Giacoso and Ricordi worked on the libretto: Illica wrote the “script,” Giacoso turned that into poetry, with Ricordi acting as a kind of referee between the two. In mid-June 1902, a copy of the revised text-so-far was sent to the composer.

Silence from Puccini. Until November. When he wrote to Giacoso asking to meet to discuss changes; followed by letters to Ricordi, Illica and Giacoso to say that the scene in the American Consulate had to go. He warned Ricordi that the scene was a terrible mistake, interrupting the inevitable progression of the tragedy, and would surely result in a fiasco. He flattered Illica, writing that Act One (the marriage of Pinkerton and Butterfly) must be his, but that Act Two must be Belasco’s, with its total concentration on the tragic plight of the heroine. The East (Japan)-West (America) culture-clash Puccini originally considered was greatly reduced. Illica agreed with Puccini’s assessment of the situation. Ricordi feared that the opera would now be too short for a full evening and would have to be performed in tandem with some other shortish piece; it took some persuasion from both Illica and Puccini to convince Ricordi the cut was dramatically necessary.

Giacoso was incensed. He agreed that the scene was not in Belasco’s play, but their first act wasn’t either; losing this scene would remove “many exquisite poetic details.” Why not, he suggested, rewrite the entire libretto to conform totally to the stage adaptation? The first act was already composed, so that was not a valid option.

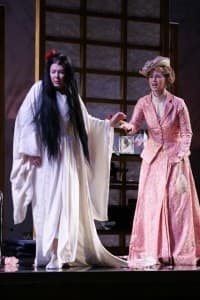

Madame Butterfly – The Minnesota Opera

Eventually he calmed down and work began on the revisions demanded by the scene’s elimination. For the scene at the Consulate contained much that was vital to the drama. As the curtain rises, Sharpless is working at his desk. Pinkerton enters; almost immediately we find out that he has been married for a year to an American who is with him in Nagasaki, and that he has told his wife about his “marriage” to Butterfly. They have no children, and she suggested they take his child back to America with them. Sharpless thinks it’s a good idea, but is horrified that Kate has already gone to Butterfly’s house. He berates Pinkerton for his callous treatment of Butterfly, who has remained utterly faithful to him for the past three years. In an aria Pinkerton recalls happy memories of his time spent with Butterfly, and his deep remorse for his neglect of her; he gives the Consul money to pass on to Butterfly, and leaves. Sharpless is disgusted. Butterfly now appears with the great news that Pinkerton’s ship arrived yesterday; she waited all night for him to come home. Has Sharpless seen him, spoken to him, why didn’t he come to the house? Does he know about the baby? Yes, Sharpless told him; in fact, he wants to take the baby with him. Butterfly is delighted at the thought of moving to America and wonders if Suzuki might come too. Before Sharpless can reply, Kate Pinkerton enters. Butterfly stands thunderstruck, staring at Kate, while the Consul signs to Kate to be silent, and quietly tells Butterfly to leave. She refuses. Kate finally notices her and approaches “la bella bambina!” Quickly she realizes who the “bambina” is. Patronizingly Kate tells her that no-one is accusing her, or blaming her: “You are a beautiful toy”. She tells Butterfly that the child will be loved and cared for; she knows it’s very sad, but it’s for the child’s good. Sharpless encourages Kate to leave – “Will she give us the child?” “In about two hours, climb the hill.” Kate leaves. Butterfly returns Pinkerton’s money, telling the consul she has no use for it. “Will I see you again?” “Perhaps. In about two hours climb the hill.” The curtain falls rapidly.

We know most of this because it was absorbed, with some minor changes, into what became the Second Part of Act Two. The scene in the Consulate does enhance the characters of both Pinkerton and Sharpless, making their roles more attractive to star tenors and baritones. But…?? Puccini was correct in his assessment – the scene does slacken the tension when it should be building towards Butterfly’s suicide.

What did the audience in La Scala read in the libretto published for that February evening? (They certainly didn’t hear much, thanks to the various whistles, cat-calls, and aspersive comments from the gallery, answered by shouts for silence!)

The first scene between Goro and Pinkerton is much as you’ll hear it today, except for Pinkerton’s reaction to Goro’s introduction, using their Japanese names, of the servants: “Stupid, silly names – I’ll call them mugs – Mug One, Mug Two, Mug Three.” Sharpless arrives, and their conversation on that February night, with Pinkerton’s two solos, remains unchanged. Also unchanged is Butterfly’s entrance with her girl-friends. Sharpless, ever the diplomat, engages Butterfly in harmless questions about her family. Harmless until he asks about her father: dead, but it’s obviously a sensitive topic. To relieve the embarrassment, Butterfly tells Pinkerton about her other relatives. One uncle is a Bonze (a traditional Japanese priest) – “incredibly wise; a fountain of eloquence,” comment Goro and the girls; the other uncle is a bit light-headed – “a drunk,” say the girls.

Sharpless wonders how old Butterfly is. He considers fifteen to be a time for playing with dolls, but Pinkerton thinks it’s the perfect age for marriage. He summons his three “Mugs” and tells them to pass around the candied spiders and flies; the nests baked in pastry; and the worst, sick-making liquor in Japan – he uses the adjective Nipponeria, which sounds pejorative.

Now arrive the High Commissioner and the Registrar; Butterfly’s relations, including her Mother , Uncle Yakusidé (the drunk), an aunt and a first cousin with her son. There follows an ensemble where some of the relatives consider Pinkerton to be beneath them while others think him handsome and wealthy; Uncle Y. is looking for wine; Goro tries to quiet everyone down; Pinkerton sings of her beauty and how she excites him; Sharpless congratulates him on finding such a treasure, but warns him that she believes in him and in this wedding.

Goro introduces the officials to Pinkerton, and each bows to the other; the relatives join the introductions with their own bowing, until Pinkerton complains that his back has done enough bowing for one day. Butterfly introduces her Mother, then her Cousin and her son and finally Uncle Yakusidé. The relatives crowd around the tables that have been laden with food; the stage direction reads: “Butterfly seats her mother and cousin close to her, trying to restrain their greediness.” Sharpless, as American Consul, formally introduces “Sir Francis Blummy Pinkerton” to the Japanese officials who reply in their native language.

Now follows Pinkerton’s conversation with Butterfly about the things she has brought with her. The Commissioner begins his wedding announcement, but is interrupted when the relatives catch Yakusidé and the child raiding the remains of the food. The official documents signed, the Japanese officials leave with Sharpless.

Pinkerton is left with his new relations. He pours whiskey for the uncle, then gives him the bottle; Butterfly stops him from offering a drink to her mother; he invites the party to eat and drink, despite Goro’s warning not to encourage Yakusidé; and he fills up the cousin’s child’s sleeves with the food that’s lying around. Then he calls for a song from his uncle who obliges with what reads like a traditional song until he is interrupted a): by noticing the child has made off with his bottle of whiskey, and b): by the arrival of the Bonze. Who denounces Cio-Cio-San and encourages the family to renounce her. They do, and leave her alone with Pinkerton. And the great love-duet begins. Which contains a lovely moment where Butterfly tells Pinkerton that initially she couldn’t consider marriage with an American: “…a barbarian, a stinging insect!” But that was before she saw him.

Now follows the “Vigil” scene that had so impressed Puccini when he saw the London production of Belasco’s play. Stage lighting depicts the transition from evening to night, to dawn, to full day. Puccini’s orchestral intermezzo portrayed the passage of time, but also hinted at Butterfly’s train of thought. At morning, Butterfly sings a lullaby to her child and takes him upstairs to bed.

A knock on the door announces the arrival of Pinkerton, his wife and Sharpless. The Consul persuades Suzuki to speak with Mrs. Pinkerton who has remained in the garden. Pinkerton recognizes that the house hasn’t changed. The librettists spliced in a few lines of conversation from the discarded Consulate scene to allow him to express remorse; in tears he gives Sharpless money to give to Butterfly, asks him to talk to her about the child, since he doesn’t dare to, and leaves. Suzuki and Kate enter from the garden. Butterfly comes down from the upstairs room; slowly the truth dawns on her. Again, lines from the Consulate scene are spliced in: Kate asks Butterfly to allow her to help the child. Butterfly tells her she will give the child to Pinkerton, but that he must come to the house to collect him. Suzuki shows Kate out of the house and goes upstairs. Sharpless offers her the money Pinkerton left, but Butterfly refuses it; their conversation is taken, with minor alterations, from the abandoned scene in the American Consulate.

Suzuki rushes in to help the almost-fainting Butterfly. She wonders where the child is and tells Suzuki to go and play with him. Suzuki refuses. Butterfly reminds her that only yesterday she had said that a good sleep would restore her beauty; “Leave me alone and your Butterfly will sleep.” She sings a verse of a folk-song: “Life and love entered with him through closed gates; he went, and nothing was left to us but death.” Again Suzuki refuses to leave. This time Butterfly commands her to go. Alone she takes the sword and reads the inscription on it. Suzuki pushes the child into the room. Passionately she bids him farewell. She gives him an American flag and a toy to play with, bandages his eyes, and goes behind the screen with the sword. We hear it fall and the dying Butterfly emerges and gropes her way towards her son. Sharpless and Pinkerton burst into the room. Butterfly dies, Sharpless takes the child, while Pinkerton falls to his knees. Fast curtain.

“Whistles and boos after the final curtain,” writes Julian Budden in his biography of the composer. William Ashbrook, in his study of The Operas of Puccini quotes from Giulio Gatti-Casazza’s Memories of Opera: “absolutely glacial silence.” (Gatti-Gasazza was La Scala’s General Manager at the time, and from 1908-1935 ran New York’s Metropolitan Opera.) Whichever is true, the performance was considered a failure; Puccini withdrew the score and returned his fee to Ricordi. But he believed it was “the most heartfelt and evocative opera I have ever conceived.” To his nephew he wrote: “I know that I have written a genuine, living opera and that it will certainly rise again.” He was convinced that, with some minor revisions, the opera would prove successful.

Both Illica and Giacoso, at various times, had objected to the treatment – or, perhaps, lack of treatment – of the ostensible hero, Pinkerton. Early in the process Illica complained to Ricordi: “Look…at the role of the tenor! Problems!…Pinkerton is unsympathetic!” Late in the process, Giacoso objected to a proposed cut of some rueful Pinkerton lines when he and Sharpless show up at Butterfly’s house in what is now the final scene. The cut, he wrote, would essentially remove the tenor from the interminabile second act (at the time there was no break after the “Humming Chorus”), inflicting serious damage to the dramatic structure. (Given that La Scala audiences had, by 1904, sat through assorted Wagner operas, Giacoso’s comment seems gratuituous.) Ricordi pointed out that Pinkerton was not a traditional leading-tenor role; on the contrary he was “a mean American leech who is afraid of Butterfly and dreads her meeting with his wife and so beats a retreat.”

It was decided that, with “minor revisions”, the opera would be given a second chance in Brescia three months later. These revisions were, in one sense, indeed minor, but major in others. The greatest difference between the two productions was that Giacoso’s interminabile second act was divided into two parts, though Puccini was reluctant to give up the idea of a two-act opera; he settled for Act Two, Part One, and Act Two, Part Two. When Puccini acknowledged Illica’s draft libretto in October, 1901, he mentioned an “intermezzo”: an orchestral version of the “Vigil” scene which had so impressed him in London. Soon he’s thinking of “mysterious voices humming.” Which became part of the seamless texture of his orchestral tone-poem of the transition from evening to the next day. Lowering the curtain at the end of so-called “Humming Chorus” meant that the audience had to be summoned back, musically, for the final scene. Major mistake on Puccini’s part, in my opinion.

Since both Illica and Giacoso had complained about Pinkerton’s scant appearances (neither of them very flattering) in the La Scala production, they must have been delighted it was decided he needed some kind of solo on his return, if only to restore his status as a primo tenore. The librettists reworked the opening of Act Two, Part Two, using material from the abandoned Consulate Scene to allow the Tenor another aria. Puccini complied with a romanza, in which Pinkerton bids farewell , essentially, to his youth.

The production at Brescia on May 28, 1904 – three months after its fiasco at La Scala – justified Puccini’s faith in the score. It was a triumph.

What changed? The Pinkerton, Sharpless and conductor were the same as at La Scala; the original Butterfly, Rosina Storchio, was on her way to Buenos Aires to sing the role there, conducted by Toscanini. Her replacement was Salomea Krusceniski, born in what is now the Ukraine; already well-known for her performances of Verdi’s Aida and Ponchielli’s Gioconda, hers was a voice considerably more “dramatic” than Storchio’s: you can compare the two on youtube! Certainly the role needs a voice which can soar over Puccini’s unleashed orchestra at the great emotional climaxes: the Love Duet in Act One; the two arias in Act Two, Part One, as well as the moment when she believes Pinkerton has returned to her; and her exalted farewell to her son in the final moments of the opera.

But, for all of Krusceniski’s vocal and dramatic gifts, she alone could not account for the success at Brescia. What revisions did the authors make? As I’ve said, not many.

The opening scene between Pinkerton and Goro remains unchanged. Sharpless arrives and their scene is the same as at La Scala. Butterfly and her friends arrive: no change. To the Consul’s admiration of the beauty of Butterfly, and his congratulations to Pinkerton, Puccini added comments, already heard, from the Friends and Relations. At La Scala, when Butterfly introduced to Pinkerton her cousin and her son, the child sang one word: “Eccellenza!”; Brescia gave it to the cousin. Butterfly confesses to Pinkerton she visited the Mission. In Milan she said she couldn’t explain it, other than that she seemed drawn more to praying to one powerful and eternal god, than to the many gods of the Japanese. Those lines were cut for Brescia.

Not until Pinkerton’s ship has been sighted were there any changes to Act 2. At La Scala Butterfly mocked her relations who advised her to forget Pinkerton; she gave the child (who had remained on-stage since he was introduced to Sharpless pages back) an American flag, and re-named him “Joy.” Which led into the “Flower Duet”. In Brescia Suzuki takes the child away during the violent confrontation between Butterfly and Goro, which allows Butterfly to sing to her most faithful friend her gloriously triumphant new lines: “He’s come back and he loves me!” Without the child, the opening lines of the duet needed changing – for the better, since it can now concentrate on gathering the flowers. Butterfly’s lines about her family’s reactions, as Suzuki is arranging her hair, were abbreviated for Brescia.

Butterfly pierces holes in the paper walls of the shoji so that all three of them can watch for Pinkerton’s arrival. Humming is heard – the music of Sharpless’s reading of Pinkerton’s letter. And the curtain, in Brescia, fell.

Suzuki, as well as Trouble, have fallen asleep during the night. She wakes up and goes to Butterfly, standing and gazing towards the harbor, still confident that Pinkerton will come. Suzuki tells her to go to bed and she’ll let her know when he arrives. Butterfly picks up the sleeping child and exits, singing a lullaby. With the arrival of Pinkerton and Sharpless we are back, briefly, in the La Scala original. What seems to have been a duet between the Consul and Suzuki, where he encourages her to talk to Mrs. Pinkerton in the garden, followed by broken phrases from Pinkerton as he surveys the house, is now a trio until Suzuki exits into the garden. Pinkerton says he can’t stay there any longer, and says he’ll wait for him on the path back to the city; he gives the Consul money and confesses his remorse. Sharpless upbraids him for his behavior and reminds him of what he told him at his wedding: “She believes in you.” Now, finally, Pinkerton realizes his mistake and admits he will never be able to forget it. Realizing he is dealing with a “mean American leech” (as Ricordi had described him), Sharpless tells him to leave: she should learn the truth alone. Now follows the tenor’s aria. Which is more a farewell to his youth than an acknowledgement of guilt for the actions of his youth; he admits he’s been “vile,” but cannot cope with the wretchedness of Butterfly’s life, and, literally, runs away from it.

Back to the original La Scala text for the remainder of the tragedy.

So, I hear you say – if you’ve followed me this far – the mere division into two parts of a questionably long second act, together with the introduction of an aria for the tenor in the opening section of Act Two, Part Two, turned the fiasco at La Scala into a triumph at Brescia? Essentially, yes, but… It’s now generally agreed that a faction in the Milanese audience (perhaps “rented” for that evening) was determined, for whatever reason, to disrupt the performance, and very successfully they did. Puccini’s confidence in a score he deeply believed in was shattered, and he spent the rest of his life tinkering with it to such an extent that we’ll never know what he really wanted.

After three years of renting to opera houses all over the world hand-written orchestral scores and parts, Ricordi felt it was time to print an orchestral score that would reflect the composer’s wishes; it was decided that this printing would be based on the Paris production. Ricordi was dismayed by the number of changes Carré demanded, but in the summer of 1906 Puccini met with the Frenchman and they quickly agreed to his suggestions.

The best change must be that of Pinkerton’s name. At La Scala and at Brescia, he was Sir Francis Blummy Pinkerton. It’s possible the name was changed either for the London production, or for Henry Savage’s one in D.C., but after Paris it becomes official. It’s also possible that Pinkerton’s racist comments about the Japanese reflected changes already made, but gone, in Paris, are his references to his “mugs,” including the speech ordering such local delicacies as “candied spiders and flies”. Carré seemed determined to reduce Pinkerton’s swaggering American naval officer (with the world as his oyster) of the 1904 La Scala and Brescia productions to a fairly non-descript “leading tenor” role.

Gone is Butterfly’s introduction of her Uncles; the drunk Yakusidé, stripped of his folk-song, and other interjections, becomes a cipher. Butterfly’s confession to Pinkerton about her visit to the Mission was revised for Brescia (cutting out her reference to the many Japanese gods as opposed to the one all-powerful American god); in Paris she didn’t sing of kneeling together with him in the same church to pray to the same god.

The wedding ceremony was reduced to its essentials, with the officials and Sharpless leaving as soon as possible. Pinkerton, alone with his new in-laws, is deprived of the chance to get his uncle drunk and hearing him sing his folk-song, for Carré cut from the family’s general toast to the couple to the arrival of Uncle Bonze.

In the duet that ends the act, Carré cut the lines where Butterfly confesses that she was not initially impressed by the idea of marrying an American – a barbarian. We get the idea, but the extra lines clarify her train of thought.

Carré found no fault in Act Two, Part One, until the scene with Sharpless. He has asked her to consider what she might do if Pinkerton never returned. Her response, addressed to her child, tells of returning to her former life as a geisha, singing and dancing. In Italy, while begging in the streets, an official would notice her son’s blue eyes and mother and child would be adopted by the Emperor and all would end happily. In France that triumphant music would become Butterfly’s determination never to return to her former life: she’d rather die.

If the Paris version of the score, which is usually performed today (and will be at Utah Opera) were all we had, we would easily, and readily, accept it as a masterly depiction of Butterfly’s obsession with her unfaithful lover. But it seems that the Paris version was but a railway station on the opera’s journey. As late as 1921 (three years before he died) Puccini “supervised” a production at the Teatro Carcano in Milan; in a vocal score that survives from that production are three hand-written additions, all taken from the original La Scala score, with a note to say that the additions were authorized by the composer.

It is sad to think that, more than a century after the first performance of what has become one of the most popular operas in the repertoire, we don’t know what the composer and his librettists were, ultimately, trying to write. What started out as a study of East (Japan)-West (American) relationships at a time when those relationships were of great interest, devolved into more of an “opera-as-usual” drama. Admittedly, the concentration on the heroine was unusual for 1904,and, even with his added “Romanza”, the tenor role remains minimal. At least the baritone is not the villain!

Who is to blame for this flawed wonder? Certainly not Illica and Giacoso, the librettists.