The Barber of Seville online course by Dr. Paul DorganPart 1: The Musical Story of Act 1 Scene 1

The title of the opera

Gioacchino Rossini’s Almaviva, o sia L’inutile precauzione had its first performance in Rome’s Teatro Argentina on February 20, 1816. The title was a mix of Pierre Beaumarchais’s subtitle to his play Le barbier de Séville – “The Useless Precaution” – and the name of the hero, Count Almaviva. An earlier operatic adaptation of the play by Giovanni Paisiello (1740 – 1816) for Russia’s St. Petersburg Opera in 1782 had proved so popular throughout Europe that it was thought better not to use the play’s original title for Rossini’s new opera, though he referred to it in letters as Barbiere. Paisiello fans filled the Argentina that night and the new opera was judged a failure. Not so the second performance, which led to Rossini’s operatic version surpassing in popularity not only Paisiello’s opera but those by four other composers whose names have been lost in the mists of history: Nicolas Isouardi (1773 – 1818); Francesco Morlacchi (1784 – 1841); Samuel Arnold (1740-1802), a British composer; and Alexander Reinagle (1756 – 1809) who produced in Philadelphia in 1794 The Spanish Barber, or The Fruitless Precaution. Footnote (if we had them!): he was British-born to a Hungarian musician-father; emigrated to NYC in 1786, but soon moved to Philadelphia, then the Capital of the newly-independent country; his music was much admired by George Washington.

About the overture

Almaviva began, as did most of Rossini’s operas, with an orchestral Sinfonia, which we would call an “Overture.” So, logically, our Musical Story should begin there. Which it does. Except that it can’t! The autograph manuscript score has no Sinfonia/Overture. Scholars claim that what the Roman audience heard on that disastrous opening night was an orchestral piece based “on Spanish themes”: apparently his Almaviva, the Spanish tenor Manuel Garcia, was not enamored of the aria Rossini had written for the hero to sing, at Figaro’s suggestion, to Rosina, and decided he’d substitute various Spanish songs to his own guitar accompaniment. Smart Rossini may well have orchestrated them to introduce them to the audience, so they wouldn’t sound totally out-of-place in the opera. Thankfully, whatever that potpourri was has been lost. The Sinfonia/Overture we now associate with Il barbiere was first heard at the La Scala premiere of Aureliano in Palmira in 1813; two years later he added 3 trombones to the score for the Sinfonia/Overture to Elisabetta, regina d’Inghelterra. It’s unclear when this already re-used piece was first attached to Barbiere. Also unclear is when the premiere’s titular Almaviva was replaced by Il barbiere di Siviglia, though we do know that six months after its Roman premiere, it was given in Bologna with the title by which we know it today; maybe then the re-cycled Sinfonia was attached to the newly titled opera? I guess we’ll never know for sure.

Confused? Me too! But read on for more confusions! According to the Critical Edition (the one based on a thorough examination of the manuscript score; various other contemporary scores; and subsequent published scores): “Rossini’s manuscript contains many approximations, contradictions and quite a few errors.” Which is, perhaps, not surprising, given that the opera was composed in about three weeks! My score has this instrumentation: 2 Flutes (doubling 2 Piccolos); 2 Oboes; 2 Clarinets; 2 Bassoons; 2 Horns; 2 Trumpets; 3 Trombones; Timpani ; Gran Cassa (a bass drum); Sistro (bell – though the Google illustration bears no resemblance to what we actually hear, which is a triangle); Piano; Guitar; Strings. It seems the 2nd oboe; 3rd trombone; and timpani which play in the Sinfonia were carry-overs from Elisabetta, for they are not required anywhere else in the Barbiere score; the piano is to be used only in the “Lesson Scene” in Act 2: though the Critical Edition says “…we may presume that the piano was the instrument currently used in the theatre at the time, and that it was used also to accompany the recitative.” It’s worth remembering that the piano in 1816 was a completely different animal from today’s instrument: its sound was gentler than we’re used to today – a gentle cat’s purr to today’s lion roar.

In his essay, The Composer at Work, in “Opera Guides #36”, prepared for English National Opera and Covent Garden productions of Rossini’s opera, John Roselli notes that many of Rossini’s predecessors were far more prolific than he and points out that “each of their works was commissioned for a particular group of singers in a particular theatre at a particular season, and could afterwards be dismantled and the best numbers recycled elsewhere – a practice which Rossini time and again resorted to in his own operatic career.” We might consider this shocking and/or cheating, but think about it: an opera proves a fiasco in Naples; so, since it’s not likely to be produced anywhere else, why not re-use the better bits of that score for an opera for Milan or Venice: audiences there wouldn’t have heard any of the music from the Neapolitan fiasco. This, let’s call it “ease of transport”, was possible because the rules governing the structure of the verses of a 19th-century Italian libretto were based on the number of syllables-per-line, rather than the number of stresses-per-line of English poetry: the slow section of an aria had to have, let’s say, ten syllables in each line, while the faster section had eight. Easy, then, to re-use music written for similar situations in two, or even three, different librettos. “Waste not, want not!” Right? But before you get on your high horse and gallop off to condemn these self-borrowings, consider the following (which would be a Footnote, if we had such a thing!) Handel was as guilty as Rossini of the same crime, if crime it be. For the last movement of his Eroica Symphony, Op. 55, Beethoven used the theme of his Op. 35 set of piano variations, composed a year before the symphony; and the choral section of his 9th Symphony, Op. 125, bears a striking resemblance to the choral section of his Choral Fantasy, Op. 80. Gustav Mahler was an inveterate self-borrower, re-using the melodies (in one instance the text as well) of earlier songs in various of his symphonies. But the most-wanted criminal in this regard should be the much-revered Johann Sebastian Bach. Self-borrowing is a petty crime compared to the 15 keyboard concertos in which he “borrowed” the solo line of a Violin Concerto by Vivaldi (six of those!); or one by Telemann; or an Oboe Concerto by Marcello; or works by various noble nonentities; and rearranged them for keyboard, giving scant credit to the original composers. Were the German audiences who first heard these keyboard concerti by Bach aware of his thievery? Of course not. No more was the Bologna audience aware that the Sinfonia/Overture they were hearing as the introduction to Il barbiere di Siviglia had been used twice before.

This Sinfonia/Overture was but the beginning of Rossini’s many borrowings in Barbiere, and I’ll point out the ones I’ve been able to track down.

Cast of Characters

Count Almaviva: Tenor

Figaro, a barber: Baritone

Rosina, ward of Dr. Bartolo: Mezzo Soprano

Dr. Bartolo, a physician: Basso buffo

Don Basilio, a music teacher: Bass

Fiorello, Count Almaviva’s servant: Baritone

Berta, Dr. Bartolo’s maid: Soprano

Ambrogio, Dr. Bartolo’s servant: Bass

Officer: Bass

Street Musicians: Tenors; Basses

Soldiers: Tenors; Basses

There is no female chorus, which may seem unusual, but really isn’t. (The dates after the operas’ titles are the years when Utah Opera produced them!) Neither Rossini’s La Cenerentola (1992; 2008), nor his L’Italiana in Algeria (1994; 2010) use a women’s chorus; there isn’t one in Verdi’s Rigoletto (1982; 1990; 2001; 2012). Obviously there were no female miners during the California Gold Rush, so Puccini’s La fanciulla del West (1982; 2004) has only a male chorus; ditto for Carlisle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men (1999; 2012), and Jake Heggie’s Moby Dick (2018). Many of you may remember Utah Opera’s productions of Benjamin Britten’s one-act “Church Parables” as part of the Cathedral of the Madeleine’s Festivals: Curlew River (1993); The Burning Fiery Furnace (1995); and The Prodigal Son (1996); which call for male voices only.

But back to Il barbiere!

The Musical Story of Part 1: Act 1, Scene 1

We are outside Don Bartolo’s house in Seville which has a balcony on the second floor. Count Almaviva’s servant Fiorello has hired a group of musicians who are determined to be as quiet as possible: “Piano, Pianissimo, without making any noise.” It’s doubtful that any of the Roman audience would have recognized that the music they were hearing is exactly the same as what the guys sang at the start of Act 2 of Rossini’s Sigismondo, which was not a great success at its Venice premiere in 1814.

The Count enters and is reassured by Fiorello that the musicians are ready to accompany him, though, again, “Piano, Pianissimo.” The following huge “ta-DUM” from the full orchestra, contradicting Fiorello’s “Softly” command, would surely be enough to waken the entire neighborhood, and the Count will refer to that in the recitative after his aria. Clarinet, accompanied by a guitar, introduces the melody the Count will sing. Maybe his nervousness at singing to his beloved is illustrated by the trumpet’s repeated notes; flute, oboe and clarinet seem to find this very funny, but stifle their laughter to allow Almaviva to start his Cavatina. By Rossini’s time this term had evolved to be applied only to the first aria for a principal singer alone, and without contributions from whomever else might be on stage. Lady Macbeth’s opening aria in Verdi’s 1847 operatic version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth has the heading Cavatina; so does Faust’s “Salut! Demeure chaste et pure” in Gounod’s opera.

One source I consulted claims that one of the choruses from Ciro in Babilonia (premiered in Ferrara in 1812) “sketches out for us the shape” of this Cavatina. “Shape” is a loaded noun: does the author mean the slow-fast form (usual in so many arias); or the contour of the melody? I won’t get technical here, but I will tell you I’ve twice watched a performance of the opera on youtube (a fascinating and imaginative production from the 2012 Rossini Festival) and listened to the sound recording of another performance (from 1988): in neither could I hear any hint, melodically or in a formal sense, of Almaviva’s aria.

Opera Philadelphia’s production of The Barber of Seville. Taylor Stayton is Count Almaviva, who arrives in Seville in pursuit of the beautiful Rosina. Photos by Kelly & Massa.

The Count’s Cavatina done, Fiorello, bringing back the opening chorus music, points out the assembled musicians: after all, dawn is approaching. Almaviva dismisses them, but pays them well enough that they must express their thanks in ever-increasing gratitude, despite the Count’s cursing their loudness and Fiorello’s attempts to quiet them down and get rid of them. Surely the neighborhood must be awake by now! Scholars talk of “The Rossini Crescendo” – whether it be in a Sinfonia/Overture; an aria; or, as here, in the chorus: the opening phrases are repeated over and over, getting louder all the time until they explode in a great climax, which must then, as here, be quieted down, though that’s left to the orchestra. Finally they leave and Fiorello does wonder if their noise might not have woken up the neighbors. Almaviva is distressed that his beloved hasn’t yet appeared: usually she comes to the balcony to breathe in the early-morning air. Wanting to be alone in case he does get to speak with her, he dismisses Fiorello, who disappears not just from the stage, but also from the score – well, not quite: see below! Continuing his soliloquy, Almaviva assumes “she” must know of his daily songs to her. An off-stage voice interrupts his train of thought, and he hides to see whose voice it is.

With an astonishing burst of energy, probably not heard before in an Opera House, and certainly not equaled in Italian Opera until, 71 years later Verdi unleashed the furious storm with which Otello opens, the full orchestra introduces us, first to that same off-stage voice which had interrupted the Count’s soliloquy, and then to the singer himself, who enters, demanding space for his extraordinary talents. Figaro’s Cavatina is one of the most challenging arias for a baritone: it’s fast; it’s high; it’s the first thing the character sings (most composers allow a singer to try out the voice in the given space with an opening recitative; not here!); and its wordy text must be clearly articulated. And all of us know it (or think we do!), and the baritone knows we do (or thinks he knows we do)! Very scary! He tells us he is Seville’s “factotum” on his way to open his shop. Life is good for a high-class barber, who must be ready, day or night, with his razors, combs, scissors or lancets (yes, back then barbers did perform minor surgeries!); in addition, there’s his side-job as a messenger between gentlemen and ladies. He is in high demand, but “Please”, he says, “one at a time!”

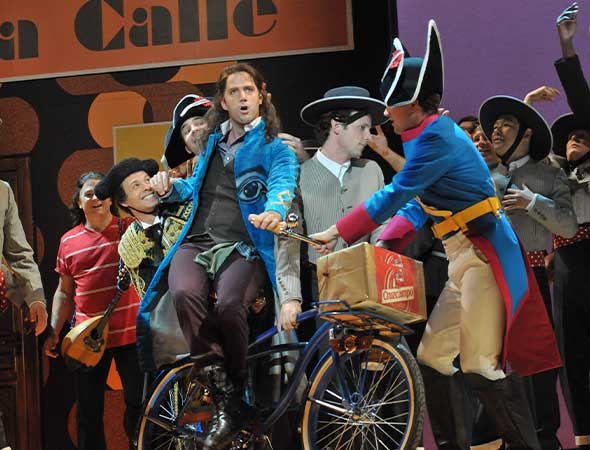

Opera Philadelphia’s production of The Barber of Seville. Figaro (Jonathan Beyer) makes his entrance with the famous aria “Largo al factotum”. Photos by Kelly & Massa.

Figaro explains more in his recitative after his Cavatina. Life is good: busy, but lots of fun, and he’s well-paid. Without his help no girl in Seville could marry: even widows need his help in finding second husbands. It turns out that Almaviva and Figaro know each other, though we never learn how they first met (a previous assignation arranged by Figaro perhaps?). The Count does not want his identity known in Seville. He fell in love with a beautiful girl he saw on the Prado, the daughter of an old doctor, and he now spends his nights under her balcony. As the barber, wigmaker, surgeon (not to mention his other services) to Don Bartolo, he’s familiar with the household: the girl is the ward, not the daughter, of the doctor; and that he… But before he can continue, the balcony door opens and the pair hide. Rosina wonders where “he” is and, of course, “he” reveals himself, much to her embarrassment; before she can deliver her letter to him, Bartolo joins her on the balcony and wonders about the paper in her hand: the words, she replies, of L’inutile precauzione – a new opera. An inside joke, since that was the subtitle of the opera at its Roman premiere! Bartolo laments that the new opera will probably be just a long boring piece of nonsense, but such is the lack of taste these days! This chunk of recitative is usually cut in performance, but it does set up Bartolo’s objection in Act 2 to the aria Rosina sings in the “Lesson” scene. “Oops,” says Rosina, “I’ve dropped it; please pick it up.” Alamviva salvages the note, so it’s no wonder Bartolo can’t find it: perhaps, suggests Rosina, the wind has blown it away. But the searching only annoys Bartolo the more and he orders her inside and determines to brick up the balcony as he re-enters his home.

Almaviva is distraught by Rosina’s evident unhappy situation. Figaro is more interested in the note they’ve rescued: “I’m curious about you. When my guardian leaves find a way to tell me who you are and what are your intentions. I cannot go on the balcony without my tyrannical guardian, but I’ll do everything I can to get away from this. Your miserable Rosina.” Again, this is usually cut in performance, but it’s interesting that Rossini has Figaro read, rather than sing, the words of the note. Back to singing as Figaro explains that Bartolo is old, miserly, and intends to marry Rosina only to get hold of her money. The street door opens and they hide. To a servant inside, Bartolo says he’ll soon be back and to admit no-one other than Don Basilio. Locking the front door, he is determined to marry Rosina today.

Basilio, explains Figaro, arranges marriages, but is always broke, and is Rosina’s voice teacher. To be reassured that Rosina loves him for himself, the Count says he will not tell her his real name, nor his rank and fortune. Maybe Figaro could…? Figaro couldn’t. But he realizes she is behind the balcony shutters, and, giving the Count his guitar, encourages him to explain his situation in song. Accompanying himself (so says the stage direction, but remember that the original Almaviva, the Spaniard Manuel Garcia, could play the guitar – hence the suspected original Roman Sinfonia/Overture “on Spanish tunes” – the Count tells her his name is Lindoro, that he adores her and wants to marry her. Echoing his final phrase, Rosina begs him to continue: the guys are delighted. In the second verse, Lindoro pleads poverty and can offer only a faithful heart which will sigh for her from morn to night. Rosina’s reply is interrupted by the closing of the balcony window, showing, Figaro says, that someone is there with her. “You must help me; arrange for me to get into the house to see her!” Figaro is initially reluctant, but when the Count mentions that money will be no object, he sings of the volcano of ideas erupting from his brain at the mere mention of cash! His opening statement consists of vocal leaps filled in by swaggering string flourishes, Allegro Maestoso; the Vivace which follows expresses his excitement at the prospect facing him: listen out for the “tri-po-let” figure which follows, because it becomes a kind of refrain, vocally uniting the guys. The Count, introduced by Flute and 1st Violin, is calmer but, to Figaro’s excited rhythms, wonders what that volcano will suggest. Disguise yourself as a soldier: a regiment has been posted to the city, and you’ve been billeted to Bartolo’s house. And, by the way, you must be drunk. Rossini must have had occasional moments of inebriation because Figaro’s explanation is a perfect vocal illustration of someone who’d be charged with DUI: if you’re drunk Bartolo will believe you. So far, so good. But the Count wonders where he might contact Figaro. Another “Rossini crescendo” as Figaro gives him directions: repeated D’s for the voice while clarinet and bassoon introduce a new melody. When it’s the Count’s verse he sings the woodwinds’ melody, but his passion carries him into elaborate vocal decorations and the duet finishes on a shared high G!

Remember Fiorello? Almaviva’s servant with the musicians in the opening scene? In the score he now reappears to complain about his master: young, wealthy and in love; which makes his (Fiorello’s) life a misery. Not even the most completest recording of the opera includes this recitative. It does, though, provide a hint as to how changes of scene might have been managed in 1816. The scene we’ve just enjoyed took place outside Bartolo’s house, and now the action moves indoors. Back then much of the scenery would have been painted flats and backdrops, though in this first scene the balcony must surely have been solidly supported. Changing from the outdoor set to the indoor one must have involved some major adjustments, and it’s probable that the reappearance of Fiorello singing some/any kind of nonsense was necessary to allow for that.