Flight online course by Ross HagenPart 1: Overview and Characters

Broadly speaking, Jonathan Dove and April de Angelis’ Flight is a comedic opera where the action revolves in a large part around a collection of couples, some of whom get along better than others, and all of whom are stranded in an airport. In a 2021 interview as part of Seattle Opera’s filmed production, composer Dove and librettist April de Angelis describe being initially inspired by Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, which is a classic comedy in a semi-Shakespearean mold, full of hilarious misunderstandings and humiliations until the proper couples are restored at the end. In the first act of Flight everyone is suddenly trapped in the airport by a storm, the second act brings dramatic revelations and no shortage of shenanigans as they overnight in the airport, and the final act sees order restored as flights resume and partners are reunited. Yet Flight introduces to this scenario the character of The Refugee, a tragic outcast who is shunned by the couples at first but ultimately provides a sort of lesson in empathy. The ending is also much less tidy than in a classic comedic opera, because while the various couples all regain a sense of equilibrium and purpose, The Refugee’s position remains unsettled. It’s likely this balance between comedy and tragedy, combined with the lyricism of the music and its potential for varied readings, that contributed to the popularity of the opera. Since its premiere in 1998, it’s been produced by over 30 different companies, a welcome surprise for its creators since it was their first full-scale opera.

In the past, when I’ve written on Utah Opera productions I’ve included a fairly detailed synopsis of the various scenes and numbers in the opera. I’ve done this partly with the knowledge that the operas are generally well-known and that there’s little sense that I might “spoil” anything about the plot by doing so (…if you’re just now joining us, I have bad news about Mimi in La Boheme and Violetta in La Traviata). After spending some time with Flight, however, it seems to me that this approach would reveal too much about how things unfold in the opera. There are too many surprises in store. Instead, I’m going to come at this from the characters themselves, exploring their roles in the drama and how Dove characterizes them musically.

Characters

The Controller: The Controller is a semi-omniscient character who also sometimes reveals a deeply misanthropic streak, much preferring the cleanliness and order of sleek flying machines to the messiness and pettiness of human drama. Indeed, she largely remains in the control tower laughing as squabbles and shenanigans take place below, although the chaotic storm in the second act definitely tests her composure. She has particular contempt for romantic entanglements, as seen in the Act 1 aria “Down You Go,” but there are suggestions that this may be a protective strategy. When not issuing announcements, she tends to soliloquize and only converses directly with The Refugee, warning him on occasion of the approach of the Immigration Officer. However, it’s unclear whether she is genuinely sympathetic towards him or if she enjoys having him under her thumb, as if he is effectively her prisoner. For example, early in the first act she addresses the Refugee (although he’s unable to hear her) and declares how she likes the fact that he’s stuck, with nothing to do but stare at her and “adore.” In the end, much of her characterization in any given production depends on the choices made by the director. Her public announcements are also always preceded by a bright chiming musical figure, not unlike those found in most airports, giving her a leitmotif of sorts that also adds a layer of realism.

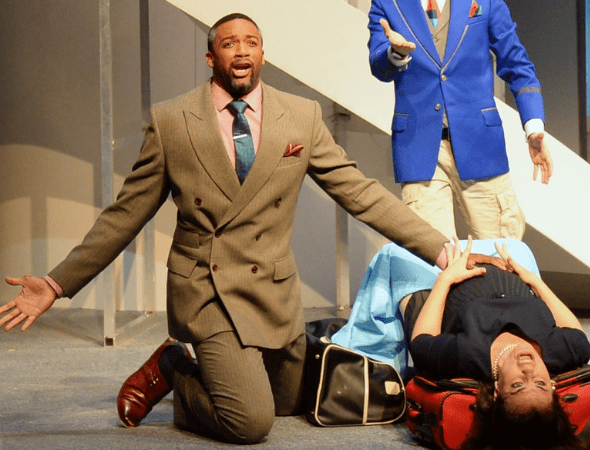

The Refugee: The Refugee is something of an in-between character, an outsider who is stuck in a place of transit and who has to try and get by on his wits. His countertenor range and occasional slides into a sort of Sprechstimme serve to further mark him as someone unfamiliar and out-of-place. When he speaks to the passengers in the terminal, initially asking for items of clothing or money, his lines are preceded by a brief chromatic figure that bears some comparison with the Controller’s PA announcement chime. In this Dove draws upon the long history of opera and cinema using chromaticism as a signal for exotic Otherness and, ultimately, magic. The Refugee’s gambit is to try and persuade the passengers and stewards to help him by giving them a special and unique magic stone that will make their wishes come true, as he can see that many of them are likewise in emotionally vulnerable states. The other passengers balk initially, and they refuse to help him when the Immigration Officer walks through, leading the Refugee to gloat when the storm causes them all to be stuck like him. This stone figures heavily in Act II, when the other characters all approach the Refugee separately to inquire about the stone and the Refugee gives each of them what they believe to be the unique stone. Naturally, this plan goes sideways when the female passengers and stewardess discover that they’ve all been given “special” magic stones, and they vent their anger on the Refugee.

These stones and the associated magical tone are given their own leitmotif of sorts, which is introduced in the first act but becomes a dominant musical driver within the second act. The leitmotif is mostly defined by its rhythmic profile, consisting of four triplet eighth-note groupings, with the same pitch on every third note, followed by two or three eighth-note pairs that also return to the same pitch on every other note. It creates a sense of oscillation relative to a single pitch, but the rhythmic shift in the last notes introduces an element of disjunction. The pitch content of the triplet leitmotif is quite flexible, varying between a 2+1 figure at first hearing but later including both ascending and descending triplets. This flexibility allows the leitmotif to permeate the second act and give it a somewhat otherworldly and magical character, as the characters express their anxieties and desires, and act on them in some cases.

Indeed, this magical, “spellcasting” sort of sound permeates much of the opera beyond just the music associated with the refugee. Much of Dove’s musical language in the opera is in a sort of post-minimalist language, with lots of undulating arpeggios and ostinato patterns that sometimes recall The Rite of Spring, but with a lot of shimmering and twinkling kinds of timbres. The stormy second act especially takes on a mystical air, as if the time almost stops, and which to my ear accurately portrays not just the “magic” element in the plot but also the disquieting uneasiness of being in a place like an airport or school at night when it’s empty. The departure and arrival of an airplane is suffused with a sense of wonder and glory that in some ways feels comedically overblown, but also effectively and sincerely conveys the magic of flight. Dove heightens this by using widely-voiced chords that impart a sense of space. This emphasis on magic also highlights the various personal transformations that take place over the evening in the airport, since magic is nothing if not transformative.

The full backstory of the Refugee is not revealed until the third act, and while it risks giving away much of the tragic circumstances that brought him to the airport, his aria “Dawn” also provides an excellent example of how Dove uses instrumentation and dissonance to convey the anxiety, noise, and icy cold of his journey.

Bill and Tina: This married couple are the only characters in the opera who are given names, and it is quickly apparent that they are embarking on a trip meant to hopefully inject some excitement and passion back into their marriage. In addition to the trip itself, they’ve brought along a guidebook on rekindling romance that they constantly refer back to, even though it too becomes a source of bickering. However, Bill is perhaps the character who has the most eventful night during the storm when, in an effort to prove to himself and to Tina that he is not “predictable,” he goes in search of the Stewardess and finds the Steward instead. Dove and De Angelis have noted that one of their original inspirations from Marriage of Figaro was the broad scenario in which one couple “fixes” another, although in this case the process of “fixing” is of a rather different sort.

Older Woman: The Older Woman is in the airport to meet her fiance, a young man from Mallorca who, as it turns out, may not be showing up. Although in some ways she is obviously suffering from magical thinking and misplaced optimism, she also provides a sarcastic counterweight to some scenes.

Steward and Stewardess: The Steward and Stewardess man the flight desks while barely concealing their burning passion and their desire to sneak off and have their way with each other. The Controller foils them at first, but the distraction of the Refugee’s attempts to avoid the Immigration Officer give them a chance to duck behind a luggage cart and get down to business, in what is almost assuredly the most graphic and hilarious “love” duet in the mainstream operatic repertoire. Yet while the storm gives them the opportunity to luxuriate in a vast expanse of uninterrupted time together, they ultimately find themselves somewhat bewildered and even a little frightened by the prospect, especially the Stewardess. They conclude that the rushed and furtive nature of their encounters is what they prefer, however the Steward ultimately finds someone else to luxuriate in for the night.

The Minskman and Minskwoman: In keeping with the general trend of naming characters according to their role, this couple is named for their destination. The Minskman is a diplomat enroute for his first day in charge of a new office, while the Minskwoman is pregnant and quite anxious about the journey. She refuses to get on the plane at the last minute and is stranded by herself in the airport while her husband boards the plane. Over the course of the opera, she also shares her anxieties about becoming a mother and losing the freedom she once enjoyed in the aria, “I bought this suitcase in New York.” Librettist April de Angelis has noted that she particularly liked the idea of including a pregnant woman in an opera since it’s not a common character to have (I’m having a difficult time thinking of another). And of course, following Chekov’s famous playwriting dictum that if a gun shows up in the first act it needs to be used in the second, if a woman is pregnant in the first act we shouldn’t be surprised if there’s a baby by the end of the opera. In order to wrap things up properly, her husband naturally makes his way back to the airport as well.

The Immigration Officer: The Immigration Officer doesn’t truly enter into the opera until the final act, although he is a constant and threatening presence at its margins. In the first act, the passengers and stewards refuse to assist The Refugee as the Immigration Officer passes through, but when he finally arrives near the end of third act they reluctantly attempt to intervene on his behalf. The Immigration Officer finds himself conflicted, and his decision (which is in some ways a decision not to decide) ultimately causes the lack of resolution for the Refugee’s character even as the other passengers embark on their new journeys.