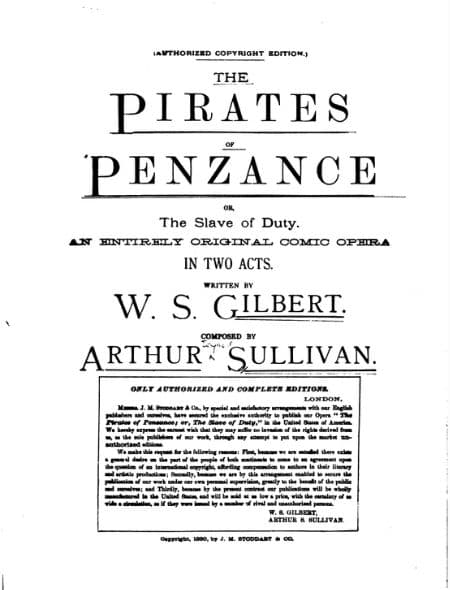

The Pirates of Penzance online course by Dr. Glen W. HicksPart 1. The Beginning

By the time the famed dramatist-composer duo William Schwenck Gilbert (1836-1911) and Arthur Seymore Sullivan (1842-1900) premiered their fifth comic operetta, The Pirates of Penzance; or, the Slave of Duty on 31 December 1879, they were already international stars. While their first three collaborations (Thespis, 1871; Trial by Jury, 1875; The Sorcerer, 1877) were all critical successes, it was their fourth, the H.M.S. Pinafore (1878) that launched them into international stardom. The Pirates of Penzance is the product of these early successes and remains a prime example of the blend of comedy, sentimentality, satire, and human nature, which Gilbert and Sullivan perfected through the interplay of music and text.

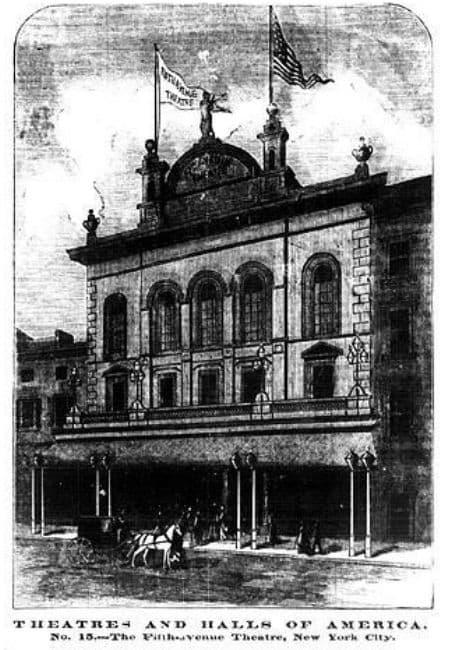

The Pirates of Penzance was Gilbert and Sullivan’s first and only work to have its world premiere in the United States. New York’s Fifth Avenue Theater was filled with laughter and cheers the night of the first performance, and critics hailed it as “brilliant and complete success.”[1] The praise came despite rampant doubts that the new operetta would be overshadowed by the success of the previous season’s triumph, H.M.S. Pinafore. Reviews of the premiere and subsequent performances place Pirates and Pinafore side by side in comparison and unapologetically praise the new work while doubting its long-term success. Referring to Pirates and Pinafore, The New York Tribune admitted “Of course every work ought to stand or fall on its own merits, but comparison in this case is unavoidable. It can hardly be doubted that any play, presented as a successor to the clever piece which had such an extraordinary popularity last season must be seen at a disadvantage.”[2]

Critics reasoned that the “doubtful” success of Pirates would be forever overshadowed by Pinafore’s memorable tunes since they were “too firmly established in the public affections to be easily dislodged.”[3] However, while the operetta is “modeled upon the Pinafore pattern,” critics agreed that Pirates was more “artistic,” “finished,” and “richer.” This assessment was rooted in the perception that the newer operetta was imbued with a higher caliber of humor. For example, a correspondent for The Era stated that Pirates is “filled with delicious strokes of satiric humor” and “absurd impossibilities.”[4] Additionally, a reviewer in The New York Times commented that “The story is exceedingly droll, full of good points, odd rhythms, and irresistibly comical situations,” making it impossible for even the most unpleasant and disagreeable of people “to refrain from merriment over it.”[5] To support this claim, the reviewer noted, “The amusement that is caused by incongruous situations and the absurd gravity with which the pretended seriousness of certain scenes is carried out were the cause of irrepressible laughter.”[6]

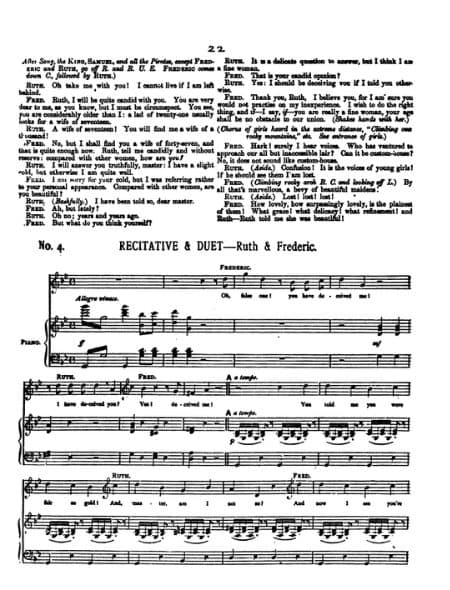

Consider the following “serious” exchange that takes place between the operetta’s youthful protagonist, Frederic (a pirate apprentice), and Ruth (“a pirate maid of all work”), early in Act 1:

RUTH. Oh, take me with you! I cannot live if I am left behind.

FRED. Ruth, I will be quite candid with you. You are very dear to me, as you know, but I must be circumspect. You see, you are considerably older than I. A lad of twenty-one usually looks for a wife of seventeen.

RUTH. A wife of seventeen! You will find me a wife of a thousand!

FRED. No, but I shall find you a wife of forty-seven, and that is quite enough. Ruth, tell me candidly and without reserve: compared with other women – how are you?

RUTH. I will answer you truthfully, master – I have a slight cold, but otherwise I am quite well.

FRED. I am sorry for your cold, but I was referring rather to your personal appearance. Compared with other women, are you beautiful?

RUTH. (bashfully) I have been told so, dear master.

FRED. Ah, but lately?

RUTH. Oh, no; years and years ago.

FRED. What do you think of yourself?

RUTH. It is a delicate question to answer, but I think I am a fine woman.

FRED. That is your candid opinion?

RUTH. Yes, I should be deceiving you if I told you otherwise.

FRED. Thank you, Ruth. I believe you, for I am sure you would not practice on my inexperience. I wish to do the right thing, and if – I say if – you are really a fine woman, your age shall be no obstacle to our union!

Passages like this one are the source of much of the humor noted by early critics and audiences. Gilbert’s texts are heavily saturated with a potpourri of jokes, wordplay, and satire, so much so that if the listener lets their attention stray for only a moment, one is at risk of missing the punchline. While many praised Pirates for its comedic prowess, some thought that the continuous onslaught of humor risked alienating an average audience that was not used to such comedic quick fire. Referring to Pirate’s humor as “recondite,” or hard to comprehend, one reviewer stated,

“[Pirates] demands a closer attention to the words than the ordinary playgoer will always give; perhaps it requires a more distinct enunciation than singers usually think it worth while to cultivate. On the other hand, there are great stores of wit and drollery in the dialogue and the songs which will well repay exploration. […] the opera ought to gain greatly upon the favor of the public after two or three representations.”[7]

Now that Pirates has received much more than “two or three representations,” it is possible to map its influence over the decades. Perhaps the anonymous critic of The New York Tribune was right, and that with each performance, the operetta has grown in favor among audiences. Since its premiere in 1879, Pirates has risen to be among the most popular of Gilbert and Sullivan’s operettas, possibly even outshining H.M.S. Pinafore, despite the doubts thrown by nineteenth-century critics. Moreover, through its cinematic adaptation (1983) and the use of its memorable tunes in television, Pirates has become an influential part of modern popular culture.

Modern staging of the operetta continues to inspire many of the same observations made by early critics. In a review of New York University’s 2017 adaptation, Ben Brantley quipped that Pirates is a “paradise of inanity,” replete with “evergreen absurdity.”[8] The timelessness of much of the operetta’s humor supersedes its Victorian beginnings and lends itself quite ably to modern contexts. With the lingering effects of a global pandemic, The Atlantic Opera’s 2022 production was deemed “a full bounty of escapist fun.”[9] In his review, Johnathan Shipley offered the following summation,

It’s just a fun show and in this age of quarantines and self-isolation, being in a hall with others snickering at silly folks singing wonderfully about silly things is something of a balm.[10]

By examining the reception history of Pirates, whether staged against a backdrop of feast or famine, it is possible to observe the persistence of humankind’s desire to laugh at itself. One London reviewer noted that the power of the operetta’s humor lies in its ability to present “a reality of human nature, however exaggerated and fancifully distorted.”[11] This distorted “reality” regularly overcomes time and culture to persuade modern audiences to giggle and guffaw at the antics of caricatures from a bygone era. Each time we laugh at the absurdity of the plot and its performers, we become connected to those first audiences nearly 150 years ago. Perhaps one critic’s observation that Pirates “can hardly be appreciated at a single hearing” is true.[12] Yet, with each performance, we have the opportunity to understand better and appreciate more fully our own condition. How fortunate that Pirates has received countless performances and shows no signs of stopping.

[1] Review, The New York Tribune, 1 January 1880.

[2] Review, The New York Tribune, 1 January 1880.

[3] “Amusements: Fifth-Avenue Theater,” The New York Times, 1 January 1880; Review, The New York Tribune, 1 January 1880.

[4] “The Pirates of Penzance,” The Era, 18 January 1880.

[5] “Amusements: Fifth-Avenue Theater,” The New York Times, 1 January 1880.

[6] “Amusements: Fifth-Avenue Theater,” The New York Times, 1 January 1880.

[7] Review, The New York Tribune, 1 January 1880.

[8] Ben Brantley, “Review: Sailing on Silly Seas With ‘The Pirates of Penzance,’” The New York Times, 1 December 2017.

[9] Jonathan Shipley, “Review: ‘The Pirates of Penzance’ offers up a full bounty of escapist fun,” ArtsAlt, 25 January 2022.

[10] Jonathan Shipley, “Review: ‘The Pirates of Penzance’ offers up a full bounty of escapist fun,” ArtsAlt, 25 January 2022.

[11] “Review,” The Times, 19 March 1880.

[12] “Amusements: Fifth-Avenue Theater,” The New York Times, 1 January 1880; Review, The New York Tribune, 1 January 1880.