The Flying Dutchman online course by Dr. Carol AndersonGerman Romanticism and Wagner

by Dr. Carol Anderson

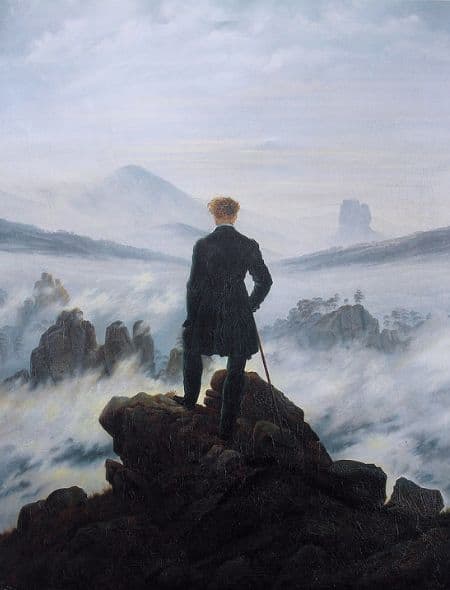

Society, human behavior, politics – for better or worse, these are all influenced by the Pendulum Effect, which states that “trends…tend to swing back and forth between opposite extremes.” That same pendulum swings between extremes in artistic styles, as happened in the shift from the Age of Reason to Romanticism. The meticulously organized, manicured elegance of the Enlightenment emphasized reason and thought. As society moved into a new century in the early 1800s, reason gave way to emotion and passion, and manicured environments were swallowed up in a primal, unkempt Nature full of supernatural elements.

This shift in thought moved throughout philosophy, aesthetics and all the arts, including literature, painting, and design.

Romantic (as opposed to small-r “romantic”) themes included use of supernatural elements, nature as a driving force, emphasis on peasant or everyday characters, and influences of folk songs and folklore. One of the most seminal and efficient examples of Romanticism in music is Franz Schubert’s Erlkönig, setting the poetry of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. In four minutes, the singer and pianist tell a horror story of a nightmare ride through the elements to save a dying child.

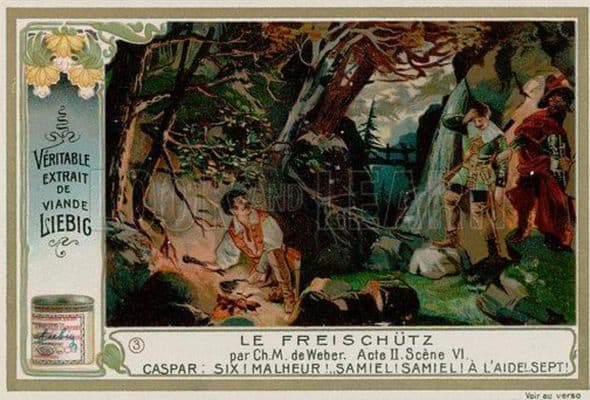

In opera, German Romanticism made its debut in the works of Carl Maria von Weber, with his 1821 opera Der Freischütz, or “The Free-Shooter.”

Freischütz tells the story of a hunter named Max who loves a peasant girl named Agathe; he must win a shooting contest to gain her hand. Ordinarily an accurate marksman, Max has been experiencing ill luck. His rival Kaspar exploits this insecurity and encourages Max to seek supernatural aid. In the terrifying Wolf’s Glen scene, Kaspar casts 7 magic bullets with the aid of evil powers. Omens, ghost stories, storms, evil spirits – all these loom large in this folktale of Bohemian life.

Other early German romantic operas include Hans Heiling’s Der Vampyr, Franz Schubert’s Der Teufels Lustschloss (The Devil’s Pleasure Palace) and comic operas of Albert Lortzing (Zar und Zimmermann). Operetta grew out of the Romantic movement as a less over-wrought cousin to the Romantic operas-von Flotow’s Marthe and Nicolai’s The Merry Wives of Windsor are early examples. The orchestra assumed a greater role in the storytelling as well, as can be heard in this excerpt from Weber’s Oberon. In the absence of a literal translation or fluency in German, the different facets of the ocean — foreboding, noble, placid, or wildly crashing — are clearly depicted in the orchestration.

Born in 1813, Wagner was steeped in these contemporary Romantic influences. His earliest encounter with opera was at the age of nine, seeing a production of Der Freischütz conducted by Weber himself. He was particularly impressed by the supernatural elements of Gothic horror. Wagner’s own output is likewise filled with natural influences, mythical or folkloric subjects, supernatural elements, and curses.

Wagner added to that mix “redemption through the love of a faithful woman,” a dramatic device that is found in most of his operas. The Flying Dutchman is the first story to include that trope. Senta has long been drawn to the portrait of the Dutchman that hangs in her home. Upon meeting the Dutchman, she pledges eternal faithfulness to him. Though her fidelity is questioned along the way, she proves true at heart and the Dutchman’s curse is finally broken.