The Flying DutchmanRichard Wagner in Search of Himself

by Michael Clive

Even for confirmed lovers of opera, Richard Wagner’s operas can represent something of a project. Wagner’s later operas, including the four-part Ring of the Nibelungs, Tännhauser, Parsifal, Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger, and Lohengrin, were revolutionary—transforming not just opera as an art form, but the history of art itself. His early operas, including Rienzi and Die Feen, are so traditional that much of their music can be mistaken for the work of other composers. A single opera stands at the fulcrum of Wagner’s early, traditionalist music-dramas and his Wagner his revolutionary later works: Der fliegende Holländer, or The Flying Dutchman. In this opera, Wagner’s contemporary audience heard much of what they had always heard in the opera house: long, beautiful melodic lines, spectacular arias, and pleasing male and female choruses—communal singing that gives us a sense of our characters’ everyday lives, providing social context for the drama. But the seeds of revolution are here. Among them are the use of short, repeated musical motifs to represent characters and philosophical ideas; a flow of music that continues without interruption; and an incredibly intense focus on characters’ inner feelings. No composer before Wagner had found a way to express with such intensity the most deeply held human emotions. After Dutchman, Wagner would begin to explore the use of long, unresolved, ambiguous harmonic progressions to express the inchoate longings of the human heart; but in Dutchman, our protagonists’ passions are unambiguous, and are there to be heard in clarion phrases.

It’s said that all art is autobiography if we look deeply enough, but in Wagner’s case, we needn’t look all that deeply. He used his operas almost like a diary chronicling his philosophical concerns and the events of his life—in this case a harrowing sea journey, his preoccupation with the redemptive power of a woman’s love, and his fascination with the many accounts of a hapless transgressor condemned to wander aimlessly and eternally by land or sea. You may know such a tale from the Gospels, or from Coleridge’s “The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner;” Wagner drew his treatment from a satirical version by the great German poet and dramatist Heinrich Heine (whose verses are also the poetry in many of Schubert’s greatest songs). Wagner’s approach is far weightier than in Heine’s humorous From the Memoirs of Herr Schnabelewopski. And as we listen to the music, we can hear the turmoil that made Wagner’s life at age twenty-six more intensely melodramatic, more riven by emotional turmoil, than any of his operas.

Wagner was already at work on another opera, Rienzi, when inspiration for The Flying Dutchman began to take shape. The year was 1839, and he was conductor at the Court Theater in Riga (present-day Latvia). Always insistent on the entitlements of his self-perceived greatness, Wagner lived in extravagant style, amassing huge debts; at the same time his wife retired from her public career on the opera stage, eliminating his best source of income. In a bid to elude his creditors, he tried to make a run for Paris and London, where he thought staged productions of Rienzi would spell the end of his debts and his troubles.

His scheme failed in every way possible, giving rise to a period of personal travails reflected in the events of the Dutchman libretto. Under the stress of trying to evade their creditors, Wagner’s wife, Minna, suffered a miscarriage. Without passports and desperate to dodge the law, Richard and Minna became fugitives, booking passage with an unscrupulous sea captain who was willing to take them on without papers. Their voyage must have been an unmitigated horror of rough seas and onboard privation, but Wagner found inspiration in the experience. In his Autobiographical Sketch (published in 1843, the same year as the opera’s premiere in Dresden), he notes:

The voyage through the Norwegian reefs made a wonderful impression on my imagination; the legend of the Flying Dutchman, which the sailors verified, took on a distinctive, strange colouring that only my sea adventures could have given it.

We can hear the pounding, surging seas in the storm-at-sea passages of the Dutchman. And Wagner, who identified himself with all his heroes, saw in the Dutchman’s story a man who, like himself, was relentlessly and unfairly hounded for a single transgression. In the heroine Senta, Wagner created one of his idealized women whose goodness redeems their men. Unfortunately, while Senta is a model of womanly devotion, Wagner eventually found Minna lacking as a partner. In matters of his own conduct, Wagner did not demonstrate the kind of self-sacrificing fidelity he expected from his women; for him, love was eternal until it wasn’t.

Wagner was a dramatist before he was a composer, and for The Flying Dutchman, as for all his operas, he wrote his own libretto. He completed a prose draft of the story in 1840; about a year later he had completed the libretto in verse. It went through various iterations, including a relocated scenario (first Scotland, then Norway) and one- and three-act versions to suit the production requirements of prospective producers (his Paris venue had secured a Flying Dutchman scenario for a ballet version and did not want an opera with similar plot points). After conducting the premiere of the three-act version much as we know it today, in January 1843, he had the sense that it was a decisive step forward in his career. “From here begins my career as poet, and my farewell to the mere concoctor of opera texts,” he wrote in an 1851 essay. To this day it remains the earliest Wagner opera performed at the Bayreuth Festival.

Would You Trade Places With Captain Daland’s Daughter Senta?

Our first sense of Senta comes from her friends: the “spinning chorus” that opens Act II, which evokes a stable, happy community with well-defined gender roles. People support each other here, and everyone works hard: The guys go down to the sea in ships while the gals stay home, lending their loyalty and support by practicing domestic arts such as spinning, weaving, and mending sails and nets.

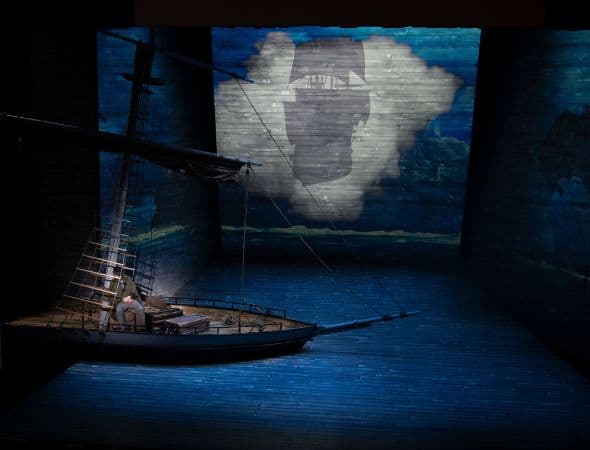

Amid this well-defined social order, it doesn’t take us long to see that Captain Daland’s daughter Senta is different from her friends. She’s moody, serious, and contemplative. Interestingly, it is a work of art that provides the foil for her character: a painting that hangs on the wall of her father’s house. When we first meet her, she can hardly stop staring at and thinking about the exotic figure in the painting: the Flying Dutchman. Wagner invites us to emulate her: He wants us to look deeply into art, as Senta does, to make us think about who we are and perhaps to reflect on the meaning of our own destinies.

Wagner burdens Senta with a dilemma for which there is no easy solution. Her steady boyfriend of long standing, Erik the huntsman, represents true affection and the promise of domestic stability. Her sense of calling to a different purpose—the redemption of the Flying Dutchman—suggests not only a rejection of traditional social norms, but also a Romantic fascination with death itself. When she meets the mysterious stranger her father brings home, her fixation only becomes stronger as it is transferred from a painting to an actual visitor. What does it say about an attractive, socially desirable young woman when the idea of suicide becomes tempting or even alluring—supplanting the possibility of a traditional marriage and family life?

Willfully transgressing social conventions, even to serve a cause perceived to be higher, was not an idea that Wagner took lightly; in his epic four-part Ring of the Nibelungs, it literally causes the end of the world. But in other operas, such as Tannhäuser, Wagner suggests that this kind of defiant, questing spirit is sometimes a prerequisite for spiritual transcendence and artistic greatness. In this way we can see that Wagner closely identified with many of the principal characters of his operas, both male and female—even in the face of seemingly irreconcilable conflicts.