The Daughter of the Regiment Online Course by Dr. Glen W. HicksPart 2. Becoming la figlia: Italian Censorship in the 1840s

Censorship has long been a part of opera’s history. From its beginnings in the early seventeenth century to the present day, constraints imposed by politics and state or religious censorship have impacted the way composers, librettists, and audiences engage with the artform. Time and time again, arias have been rewritten, characters names changed, locations altered, and history reinvented all for the sake of protecting the powerful and the offensible.

History teaches us that no one was above the reach of the censors. Mozart was required to remove “anything that might offend good taste or public decency” from his opera The Marriage of Figaro (1786). Verdi famously battled with Venetian censors over his politically charged Rigoletto (1851). Even in the twentieth century, Strauss was required to tone down scenes for a London production of his opera Salome (1905). For centuries composers have dealt with political entities, religious institutions and leaders, and others who claimed to be defenders of “good taste.” Consequently, it comes as no surprise that Donizetti’s La fille du régiment underwent several changes to appease Italian censors during the 1840s.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Italy was home to more opera houses than any other region with approximately forty new operas (sometimes more) produced every year. Before the creation of the Italian nation in the 1860s, these operas houses were required to submit every idea for a new opera to the local authorities for approval.[1] If approved, a libretto could be written which also had to be approved. The justification for such scrutiny was fueled by the fear of uprising or rebellion that authorities believed an opera could insight. Carlo Caruso, professor at the University of Siena, confirms that the social nature of an operatic performance was cause for concern.

From the point of view of public order, opera houses could be as problematic as taverns, or even brothels. In fact, operatic performances rapidly gained a reputation as events dangerously inclined to uproar and riots, and the passions stirred in audiences by the skilful and powerful combination of words, music, scenery and action on stage could not but add to the problem.[2]

It was for reasons like these that La fille du régiment underwent several transformations to put Italian censors at ease.

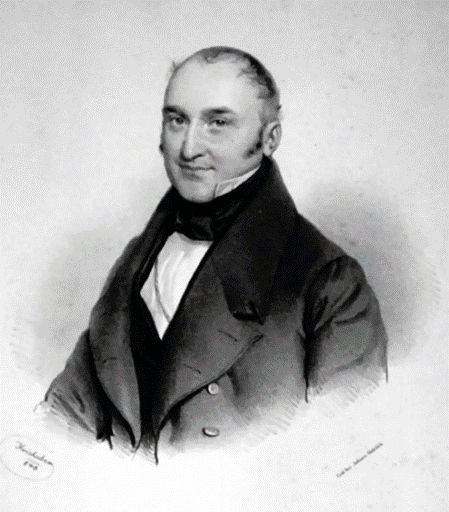

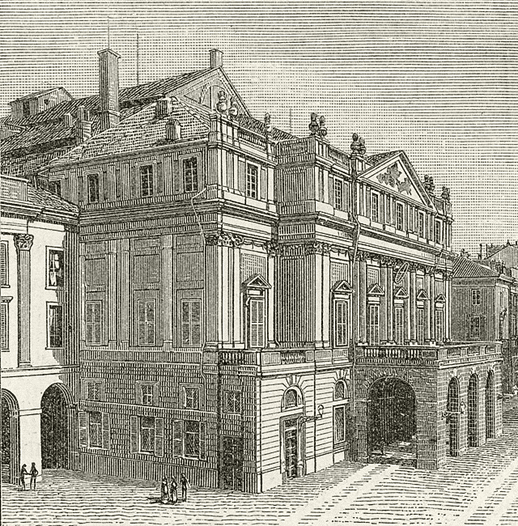

In September 1840, only seven months after the Paris premiere, Bartolomeo Merelli, impresario at La Scala in Milan, wrote to the local Austrian officials about the prospect of bringing La fille du régiment to Italy.

The undersigned would like to produce as soon as possible the opera La figlia del reggimento by Signor Maestro Donizetti, and for that reason submits the related libretto, already preventively adjusted according to the views of the Imperial Royal Censorship, for its definitive approval, and offers his profoundest regards.[3]

The libretto, translated by Calisto Bassi, had been preemptively censored in anticipation of governmental pushback. The preventative work of Merelli and Bassi seemed to have paid off as no further changes were required. Two weeks later, La figlia del reggimento received its first Italian performance at la Scala, but was pulled after only six performances.

Subsequent presentations were staged in one Italian state after another throughout the 1840s, but what seemed to be good enough for censors in Milan proved to still be problematic in other locations. Over the next ten years, La figlia del reggimento would undergo multiple transformations. Professor of Music at the University of Southampton, Francesco Izzo, suggests that what had originally caused the greatest concern for Merelli and the Italian censors was that the plot of Donizetti’s opera “unfolds against the backdrop of the French invasion of the Tyrol – a territory of the Austrian empire.”[4] The close relationship between Austria and the Italian states resulted in an environment where the unabashed patriotism and French flag waving in the original version of the opera was unwelcomed and drastic alterations needed to take place.

Through the efforts of individuals like Merelli, Bassi, and others, profound changes quelled the overtly nationalistic and patriotic themes contained in the original French libretto. Take for instance Marie’s entrance in Act One as she sings “Au bruit de la guerre.” The French version references the glory of her French homeland, the martial sounds of war, and eventual victory. The Italian version is much less direct.

French Version

To the roar of war I was born.

To everything I prefer the sound of the drum,

Without fear towards glory I march all of a sudden.

Italian Version

I was born on the battlefield:

the sound of the drum is my only pleasure.

The brave heart hastens to glory:

“Savoy and victory” is the cry of honor!

Izzo notes that Italian censorship prompted the changes to the libretto to suppress references to the nation, army, and the French flag.[5]

In [La fille du régiment], nationalism pervades the entire text, and the plot unfolds against the backdrop of the French invasion of Tyrol. It is obvious that the Milanese censors could not allow the onstage representation of France taking military action against a territory of the Austrian empire. Thus, when Bassi translated the libretto, he was forced to move the setting from the Austrian Tyrol to neutral Switzerland.[6]

The new geographic setting resulted in the sponging of the Tyrolean identities of the opera’s characters: Tonio became a “giovane svizzero” or a “young Swiss” and the chorus changed to a group of “paesani svizzeri” or “Swiss villagers.” However, the relocation to Switzerland was only the beginning. As Izzo notes, “France was removed altogether from the libretto” and was either replaced by Savoy, a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps, or rendered totally generic. Take for example the unapologetically French cabaletta “Salut à la France” from Act One. In Bassi’s Italian version, all traces of France have been replaced by generalized “heroes” accompanied by the sound of cannon fire. However, a third version in Italian by an unknown translator, distances the text even further from the original.

French Version

Hurrah for France!

For my happy days!

For hope!

For my love!

Hurrah for glory!

Together with victory,

here is

the moment of happiness

for my heart.

Italian Version (Bassi)

Who was born to the roar

of the cannon

despises the empire

of a vain splendor.

Ah! long live the glory

that surrounds the heroes!

The peace of my heart

gives me my victory.

Italian Version (anon.)

Of a desired joy,

of a tender affection,

I already feel in my breast

the arcane power.

It is the soothed anger

of my enemy stars,

to my happy days

my thought returns.

By the beginning of the 1850s, Italian performances of La figlia del reggimento had diminished drastically.[7] The complex and politically charged issues surrounding its censorship likely played a part in this drop in popularity.[8] After undergoing change after change, the text, and as a result, the music, became so far removed from their original context that the effectiveness of the original was lost in translation. Opera conductor and writer Burton Fisher observed the following of the original French version of La fille du régiment:

Donizetti’s score is notable for its adroit mixture of animated military ambience, together with descriptive pastoral moods. The composer managed to incorporate the “French ambience” to such an extent that the opera has been envisioned as a patriotic French opera, one that seems to burst over with Gallic wit and charm. In the end, Donizetti’s elegant melodic inventions provides a charming, subtle satire – an affecting comedy of manners that remains far removed from the vulgarity of farce.[9]

The original “French ambiance” and “Gallic wit” obviously proved effective in France as audiences were able to relate to the opera’s patriotic overtones. However, in Italy, it was much more difficult for audiences to connect with the work on the same emotional level.

Eventually, references to France made their way back into the opera as political allies changed and the popularity of La fille du régiment has steadily increased ever since. Today, audiences around the world enjoy Donizetti’s opera in French, Italian, German, and English. Free from the constraints of censorship, the opera is able to retain its intended effect regardless of language.

[1] Fred Plotkin, “When Verdi was Savaged by the Censors,” New York Public Radio, 29 May 2012. https://www.wqxr.org/story/212895-when-verdi-was-savaged-censors/ (accessed 4 November 2022).

[2] Carlo Caruso, “Three cases of censorship in the opera theatre: Mozart, Rossini, Verdi,” The Italianist 24 (2004): 208.

[3] Quoted in Francesco Izzo, Laughter Between Two Revolutions: Opera Buffa in Italy, 1831-1848 (New York: University of Rochester Press, 2013).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Donizetti, Gaetano, La Fille du Régiment: Opera Study Guide with Libretto, ed. Burton D. Fisher (Florida: Opera Journeys Publishing: 2018), 13.