Rigoletto Online Course by Paul DorganPart 4. Biographies of the Creators

by Paul Dorgan

Composer Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813, in the village of Le Roncole near Bussetto, a small city in Northern Italy. At that time the area was governed by France, so the greatest Italian composer was actually born a French citizen! He was an intelligent child who, at the age of 4, was studying Latin and Italian privately, before enrolling in the village school two years later. Musical talent reared its head early: when he was 8 his parents bought him a spinet which he kept for the rest of his life and is now in the museum of La Scala. Soon he was assisting the local organist; after he had moved to Bussetto at the age of 10 to continue his education, he returned to Le Roncole as often as he was needed for various church services. Bussetto had an orchestra and also an elementary kind of music school where the teenager thrived, even composing an overture for a touring production of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. A wealthy local merchant, Antonio Barezzi, virtually adopted the young man and, with other Bussettani, collected enough money to send him to study at the Conservatory in Milan.

In the summer of 1832 Verdi duly moved to Milan and auditioned for the Conservatory; he was rejected (“He will turn out to be a mediocrity” was the opinion of one of the adjudicators!) though his age, and the fact that he was a “foreigner” (i.e. from a different province) adversely influenced the panel. He was advised to study privately. He found Vincenzo Lavigna whose own operas had been successful at La Scala. He had supervised the first performance there of Don Giovanni in 1814, and ended his career there with the premiere of Bellini’s Norma in 1832, the year of Verdi’s arrival in the city. Milanese musical circles soon became aware of a talented conductor and composer, but that promising career was cut short by his forced return to Bussetto, where it was assumed he would take over the position of organist left vacant by the death of his former teacher. Those of you who have been following the recent shenanigans with Silvio Berlusconi will know that politics in Italy are never simple, and that every appointment, even that of church organist and conductor in a small city, is larded with more political fat than any law that might manage to make its way out of Washington! We musicians must rejoice in the fact that Bussetto was split over the appointment, with each candidate’s supporters meeting in “their” coffee-shop and restaurant; even the police were alerted to the possibility of violence and there were some kerfuffles.

Piqued by the politicking, Barezzi sent his protégé back to Milan in 1835 where he resumed his studies with Lavigna though not with the intensity his teacher would have liked. Verdi reconnected with a group of amateur singers and instrumentalists, the Filodrammatici, whom he had conducted when last in Milan. They presented oratorios as well as operas; the director of the group promised to find Verdi a libretto so he could compose an opera for them. The back-and-forth between Bussetto and Milan intervened, and we know nothing about the libretto, except that its author was to have been someone named Tasca.

Finally, in March 1836, Verdi’s appointment in Busetto was approved. His official church duties included composing for the various services; in addition he became conductor of the city orchestra which presented a varied repertoire of his own compositions and arrangements of popular operas. In April he became engaged to Margherita, the daughter of his mentor Barezzi, and the couple were married in May. Now there are letters to Milan about an opera, virtually complete: Rocester, with a libretto by Antonio Piazza. Since the two month’s vacation from his Bussetto appointment would not give him enough time to prepare the score with the Filodrammatici, Verdi tried to interest the Impressario at Parma, but he was not interested in presenting new works. In 1837 a daughter, Virginia, was born. In 1838 he was back in Milan trying to find a theatre for his opera, and to find a publisher for songs he had written; the songs were published, but the opera languished.

In July a son, Icilio Romano, was born, but that joy was overshadowed by the death of Virginia the next month. The young couple decided to quit Bussetto for Milan, where they arrived in February 1839 with the complete score of “my opera”. Every year La Scala presented a concert for the benefit of the Pio Istituto, a charitable organization which gave financial assistance to the widows and children of Milan’s professional musicians; Verdi’s Milanese friends managed to have the opera, which had become Oberto, selected for this performance. The tenor got sick and the performance was cancelled. The composer considered returning to Bussetto for good when he was summoned to the theatre by the impressario, Bartolomeo Merelli. He had overheard the singers discussing the high musical quality of Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio and offered to produce it in the autumn. On November 17, 1839, Verdi’s first opera was presented for the first time. The critics, for the most part, were encouraging; thirteen more performances were given that season; and the publisher Ricordi bought the score. Quite an achievement for the “mediocrity” from Bussetto! The following year the piece was given in Turin, and in 1841 both Naples and Genoa produced the opera.

This would be the place for a footnote, if this was the place for them. It isn’t, so there isn’t! BUT! It is important to bring to your notice Verdi’s pre-Oberto operatic attempts. I’ve mentioned Rocester, and Verdi implies in a biographical sketch that he sent, in 1879, to his publisher Giulio Ricordi that Oberto was merely a touched-up version of Rocester. Perfectly plausible: librettos were often revised with titles and characters renamed. Except that a letter from Verdi in 1871 says that Oberto was a revised version of Antonio Piazza’s Lord Hamilton. What, then, was “my opera”, which Verdi brought with him to Milan in 1839? We will never know. Verdi had a habit of destroying music which, for whatever reason, was cut from the score during rehearsals. Julian Budden (whose 3-volume “The Operas of Verdi” is extremely technical musically, but, despite that, is essential reading for anyone interested in the composer and his works for the stage) argues for a revised Rocester.

The success of Oberto prompted Merelli to offer the young composer a contract for three operas at intervals of eight or nine months to be performed either at La Scala or at the Kärntnerthor Theatre in Vienna, of which he was also the Director. Another achievement for the “mediocrity”! For the first of these operas Verdi ignored Merellis’s suggested libretto, and chose, instead, one by Felice Romani, Il Finto Stanislao, which was renamed Un giorno di regno. Romani was a distinguished writer of distinguished librettos: La sonnambula, I puritani and Norma for Bellini; Anna Bolena and L’elisir d’amore for Donizetti. The first performance, on September 3, 1840, was a total disaster and was immediately replaced by a revival of Oberto. In that biographical sketch of 1879 Verdi tells us that in the summer of 1840, when he would have been composing this comic opera, his wife and children died. But Virginia died in 1838 in Bussetto, while Icilio died during rehearsals for Oberto. What is true is that in June of that year Margherita died. Verdi returned to Bussetto with his father-in-law and wrote to Merelli asking to be released from his contract. Merelli refused. Undoubtedly it would be difficult to write any opera, let alone a comic one, after the death of a spouse; but Romani’s libretto was problematic: comic opera was in the midst of a transition, and the inexperienced Verdi was not yet the composer to bridge the stylistic gap. Ironically five years later the opera, renamed Il finto Stanislao, was a huge success in Venice, and, in 1859, in Naples.

The fiasco didn’t faze Merelli: he simply revived Oberto and sent the composer a libretto for the second of the contracted operas. Verdi’s memory in 1879 is not quite accurate here, either: well, let’s say it’s the accurate account of a man who wants to establish his own version of his life for posterity! Verdi refused to set Il Proscritto, the libretto sent to him; so Merelli gave it to Otto Nicolai, a German composer who had had a huge success in 1840 with Il Templario, and sent Verdi the libretto Nicolai had refused. His wife’s death, combined with the failure of his second opera, made Verdi seriously consider returning to Bussetto to be a small-time organist/conductor/composer; he threw the libretto aside, but something kept pulling him back to Nabuconosor. The score was ready by autumn of 1841, but now Merelli was reluctant to put it on. There are accounts of conflicts and rows through the autumn which eventually were resolved and the opera had its premiere on March 9, 1842. It was a complete triumph. Audiences and critics went wild and there were over seventy performances at La Scala that year alone; other Italian theatres produced it and Donizetti conducted it in Vienna the following year.

The success of Nabucco established Verdi as the most important young Italian composer of the day. But the opera was important to Verdi for another reason. The role of Abigaille was sung by Giuseppina Strepponi, who would have sung the soprano role of Leonora in Oberto had the Benefit performance in 1839 not been cancelled. Aged 26 in 1842, she was physically worn out and her voice was but a shadow of its former glory: seven years of unremitting travel from theatre to theatre throughout Italy, with frequent forays to Vienna, had taken its toll. As had the three or four illegitimate children she birthed in as many years, and the emotional turmoil from a succession of bad love-affairs. Around this time she was diagnosed as pre-consumptive and advised to stop singing. But she had a contract for a new opera by Verdi at La Scala. When she arrived for rehearsals the young composer was very concerned about her ability to get through the role of Abigaille (even today very few sopranos sing it) ; Donizetti, perhaps a bit bitter after her poor performance in one of his operas, said that Verdi didn’t even want her in the role but that Merelli had insisted. One critic at the opening night noted that she was the only singer who received no applause. Nabucco essentially marked the end of her singing career, while it was the start of the composer’s. But it was not the end of her relationship with Verdi.

I Lombardi alla prima crociata, first performed at La Scala on February 11, 1843, the third of Merelli’s commissioned operas, was, like Nabucco, a huge success with the audience. This time, though, the critics took a somewhat superior attitude, as if to make it clear that, while they could be fooled once by Nabucco, they were not about to be fooled a second time. Audiences loved seeing Italians, or, indeed, any “nation” united against a common enemy, especially if they sang a unison hymn praying for victory. The prototype had been the chorus of Hebrew Slaves, Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate, which was regularly encored whenever Nabucco was performed – even today it is Italy’s second National Anthem! These years marked the beginnings of the Risorgimento, a movement whose aim was to rid Italy of the various foreign “oppressors” who ruled various chunks of Italy and to unite the country under an Italian king: Victor Emmanuel. Verdi, writing operas dealing with peoples struggling to achieve independence from foreign rule, and writing unison choruses with catchy tunes praising freedom from the oppressor, was co-opted by the movement; and we shouldn’t dismiss the notion that Verdi opted for those plots, knowing full-well that they would be crowd-pleasers! “Viva Verdi!” was a common graffiti. But “Verdi” was an acronym for Vittore Emanuele, re d’Italia (Victor Emmanuel, king of Italy). What young composer would object to that kind of “product placement”? Politics and Verdi seemed destined for each other!

With two hits at La Scala, offers flooded in. When in Vienna for Nabucco, Verdi met the impressario of La Fenice in Venice, who asked for an opera, but the composer was already committed to his third contracted opera for La Scala: I Lombardi alla prima crociata. They agreed on a new piece for the following season. Ernani was first performed there on March 9, 1844. Verdi described the years that followed as his “galley years”, and, with this catalog of operas, it’s obvious why he felt he was a slave, enchained to an oar in some ship.

Ernani. Venice. March 9, 1844.

I due Foscari Rome. November 3, 1844.

Giovanna d’Arco Milan. February 15, 1845.

Alzira Naples. August 12, 1845.

Attila Venice. March 17, 1846.

Macbeth Florence. March 14, 1847.*

I Masnadieri London. July 22, 1847.

Jérusalem Paris. November 26, 1847. **

Il Corsaro Trieste. October 25, 1848.

La battaglia di Legnano Rome. January 27, 1849.

Luisa Miller Naples. December 8, 1849.

Stiffelio Trieste. November 16, 1850. ***

Rigoletto Venice. March 11, 1851.

Il Trovatore Rome. January 19, 1853.

La Traviata Venice. March 6, 1853.

*Macbeth was quite extraordinary in many ways for its time. While it wasn’t the only opera without the usual soprano-tenor love-interest, it packed a more powerful emotional punch than its predecessors, and was far more advanced, musically, than its contemporaries. Verdi was very aware of this and there are reports of his incessant demands to rehearse his protagonists! Macbeth’s “dagger” monologue; his duet with Lady; the ensemble after the discovery of Duncan’s murder; Banquo’s apparition at Macbeth’s banquet; all show a composer sure of what he wanted and sure of how to achieve it. The scene of the apparitions in Act 3 must have astonished with its weird sounds. And of course there is the magnificent Sleepwalking Scene for Lady – one of the greatest mad scenes ever composed! Alongside these great moments are laughable ones, usually when the chorus of witches is singing and dancing and casting spells and generally having loads of fun with their newts’ eyes and frogs’ toes! The version we usually hear today is the revision made for Paris in 1865. By then Verdi had a more refined ear for orchestral coloring, so many details of scoring were touched up; Lady’s second act aria, stylistically old-fashioned in 1865, was replaced with something far more sophisticated, as was the chorus of Scottish exiles in Act 4. Despite these changes, much of the 1847 score was untouched.

This is the first of three Shakespeare operas by Verdi: the other two are his final masterpeices, Otello and Falstaff. Verdi often proclaimed his love for Shakespeare, whose plays he continually read and re-read (in various Italian translations). Most musicians rightly revere these three operas, but many of us mourn the Shakespeare opera Verdi never wrote: Re Lear. In 1850 he and Salvatore Cammarano, who had provided Donizetti with many librettos (including Lucia di Lammermoor) discussed the play – not exactly a “discussion”: the composer told the librettist how it should be adapted for the opera house, but it became increasingly clear that Verdi’s ideas were too radical for the older, more traditional librettist, and the subject was dropped, though a draft was written. (Footnote, which isn’t a footnote: in 1850 he received an offer from London to set The Tempest and one, from Italy, for Hamlet; both were turned down because of time constraints, and never again considered.) Lear was suggested as a possible subject for Venice in 1851, but the theatre’s lack of a suitable baritone put it out of consideration. In letters beginning in 1853 he directs Antonio Somma, a well-known poet and fledgling librettist, to look at the play; a libretto was finished shortly before the Parisian premiere of Les vêpres siciliennes in 1855. Home from Paris, Verdi had three projects in mind, one of them Lear, most likely for the 1857-8 season in Naples. Again the casting of the three principals (Cordelia, the Fool and Lear – soprano, contralto and baritone) preoccupied the composer. In September the frustrated impressario wrote “Give us King Lear; eventually you may find a better Cordelia, but you won’t find a better baritone, tenor or bass.” Interesting that he doesn’t mention a contralto! But Verdi would not budge about the soprano; he offered a different subject, and the management agreed. Fast forward seven years. The director of the Paris Opéra tried to tempt Verdi back to his theatre by suggesting Lear or Cleopatra (not Shakespeare’s unwitherable temptress!). Verdi replied that Lear would offer none of the visual splendor Parisian audiences expected; besides, “it’s almost impossible to find a Cordelia.” And that, for Re Lear, was that.

** The Académie Royale (or Impériale – depending on France’s ruler of the day) de Musique in Paris could not be ignored by an opera composer. Paris was the musical capital of Europe and its principal opera house (known simply as the Opéra) was the center of that capital, so to receive a commission from the Opéra meant that a composer had “arrived”. Rossini had triumphed there, as had Donizetti, and now Verdi was asked to follow in their footsteps. With a mere four months before the scheduled premiere Verdi literally followed Rossini’s footsteps: he decided to take an earlier opera and Frenchify it. There would, of course, be a new plot which would require new numbers, but it was certainly a lot less time-consuming than starting from scratch. Thus I Lombardi became Jérusalem, which was first given November 26, 1847. Opéra audiences were more sophisticated than their Italian counterparts; they preferred, for instance, more continuous music, with the various numbers linked by orchestral commentary, rather than the stand-alone ones the Italians loved because they could applaud the singer. They also expected a more interesting orchestral accompaniment. The required ballet occurs, as required, in Act 3 and is probably the worst part of the score. Neither the French score nor its Italian version, Gerusalemme, were particularly successful. The opera is, however, an important step in Verdi’s development as a composer, for it introduced him to a better musical world than was available to him in Italy, even at La Scala. French operas at the time were far more interestingly put together than the Italian variety: plots were carefully constructed; there was a longer rehearsal period, allowing for more detailed work, musically and dramatically; there were opportunities for huge choral scenes; and the larger, and more able, orchestra allowed for greater variety of textures.

*** However much Verdi may have believed in the musical worth of Stiffelio in 1850, Aroldo did no favor to the earlier score. Music written to express the emotions of an Austrian protestant minister married to an adulterous wife could never be successfully grafted on to a plot concerning a thirteenth-century Saxon knight. Despite the musical improvements, and there were many, for Verdi gained in musical polish with each score, the Saxon in 1857 fared no better than had the Austrian minister!

Two years after the fiasco of La Traviata, and one year after its triumph at another theatre in Venice (again, Verdi “forgot” that he re-wrote some of it) the first of his “original” as opposed to “adapted” French operas was produced: Les vêpres siciliennes. In 1857 Simon Boccanegra was given in Venice. Verdi declared it another fiasco: the audience considered the plot too austere when it wasn’t confusing. In 1880 Ricordi persuaded him to revise the piece for a production at La Scala, which opened on March 24, 1881. The plot remains austere, but the additions suggested by a new librettist, Arrigo Boito, (who was also a composer) raise the dramatic stakes and add three or four dimensions to the characters, especially Simon.

Why Verdi selected a 15-year-old French libretto that had already been set three times is anyone’s guess. And, since it was destined for Rome, why a subject that showed the on-stage assassination of a legitimate king? Naturally there were all sorts of problems with the Roman censors, but Un ballo in maschera is a stunning work. Musically it’s as if Verdi, in 1859, needed to stand for a moment to consolidate his achievements while still managing to push ahead. Riccardo may well be one of his most complete heroes before Otello; from France, by way of Mozart, comes the page Oscar – a soprano playing a boy, who contrasts brilliantly with the darker soprano of Amelia, and with the subterranean sounds of the fortune-telling Ulrica. Humor, which we don’t usually associate with Verdi, is present, even if it is horribly ironic.

After Nabucco the composer and his Prima Donna never lost contact with each other, though each pursued their rising and falling stars. In 1847 Giuseppina Strepponi had established herself in Paris as a teacher of voice to young ladies. Verdi visited her there on his way to London. After I Masnadieri he decided to stay in Paris: after all, he did have to transform I Lombardi into Jérusalem, and Giuseppina offered lots of practical advice in his dealings with the Opéra. Then all those revolutions blew up throughout Europe in 1848 – even Paris was not immune, and the couple moved out of the city. Biographers don’t know when she became his mistress but are fairly sure that in 1849 she moved into Verdi’s house, the Palazzo Cavalli, in Bussetto. The local citizenry pried and sniffed to discover something about the woman who lived there in virtual seclusion: few people were invited to the house and those who were saw only Verdi. Some may have known about her checkered past: a brother-in-law accused Verdi of bringing a prostitute to live with him. The move to his farm at Sant’Agata in 1851 only substituted one kind of isolation for another, but they each must have felt a certain measure of freedom, living miles away from the prying eyes and sniffing noses of the Bussettani! The one unanswered question – was the composer married to this woman? – was finally answered on August 19, 1859, when, in the village of Collange-sous-Salève, near Geneva, with the coachman and the bell-ringer as witnesses, the couple were married.

An intriguing offer arrived in 1860 – a letter from an Italian tenor now based at Russia’s Imperial Theatre in St Petersburg. Discussions followed and eventually an adaptation of a Spanish play was agreed upon: La forza del destino. Verdi had known the play for about 10 years: it had surfaced every now and then as a possible subject. In preparation for the stay in St. Petersburg there are wonderful letters from Giuseppina about supplying a regular diet of Italian food and wine! The Verdis arrived in December 1861 to find the soprano ill; she stayed ill, so the production was postponed for a year. In the interim the Verdis left Russia, returning a couple of months before the premiere on November 10, 1862. The opera was not a huge success in St Petersburg, nor was it in Madrid a few months later. Despite a successful revision for a production at La Scala in 1869, the opera has never established itself fully in the repertorie. There’s no denying the epic sweep of the piece, nor the wonderful musical moments, but the balance between the epic and the domestic is unsure and the result is confusion for the audience. That balance would soon be corrected.

In 1865 a friend from Paris arrived at Sant’Agata with a libretto, Cleopatra, and the scenario of an adaptation of Friedrich Schiller’s play Don Carlos; he had been sent by Emile Perrin, the director of the Paris Opéra, to lure Verdi back to his theatre. Schiller’s play had been considered and set aside about a decade earlier. Thankfully so. For only now was Verdi equipped to tackle this vast drama of politics, religion, love and duty set in 16th-century Spain. As usual at the Opéra, there were all sorts of problems during rehearsals. For one thing, they dragged on too long for Verdi’s taste. Changes were made and then re-made. The dress-rehearsal, when it finally happened, lasted about five hours, albeit with four long intermissions. Further cuts. On March 11, 1867, Don Carlos opened to a tepid reception. Verdi left after the opening; over the course of its run of forty-three performances additional cuts were made (without the composer’s knowledge).

The first performance in Italian took place at London’s Covent Garden on June 4, 1867. Presumably Queen Victoria did not attend. (She had graced the opening of I Masnadieri twenty years earlier and was not amused: “A new opera by Signor Verdi”, she wrote in her diary, “the music very noisy and trivial.”) The first performance in Italy was in Bologna in October. In general the opera proved too long, even without the ballet, for Italian audiences. Eventually Verdi was persuaded to shorten it: a version in four acts was given in 1884, and two years later a shortened version of the French first act was added. In the 1970s much of what Verdi had cut before the Paris premiere was discovered in the Opéra’s library, and the breadth of the conception was revealed in all its glory! This is far grander than had been imagined, and we can only regret that the dinner demands of the audience, which required an 8pm start, and the schedule of the Parisian public transit system, which demanded a final curtain before midnight, necessitated such butchery! Verdi’s original can’t be entirely restored in the theatre – he used some of the music in his Messa di Requiem – but we can hear it in a recording conducted by Claudio Abbado, pretty much as Verdi originally intended. In no other opera, neither Otello nor Falstaff, does Verdi probe the minds of his characters as he does in this score. The growing love in the opening scene between Carlos and Elisabetta which is then thwarted by politics, but still vibrantly alive in their heartbreaking duet in the final scene; the friendship between Carlos and Posa; the political relationship between Posa and the King; the King’s realization that his wife has never loved him; the confrontation between the King and the Grand Inquisitor who demands the arrest of the king’s son: scene after scene of the highest dramma per musica! Considering that audiences are content to sit through five hours of a Wagner opera, their apparent inability to sit through a mere four for a stupendous Verdi score is a tad unreasonable!

In January 1867, in the midst of rehearsals for Don Carlos, Verdi’s father died. It had not been an easy relationship; in 1851 the son had gone so far as to have a legal document drawn up effectively divorcing his parents. In July his father-in-law, Antonio Barezzi, died after a long illness: “I owe him everything, everything, everything.” In December Francesco Maria Piave, the author of nine librettos for Verdi, including Ernani, Rigoletto and La Traviata, was paralysed by a stroke. Verdi immediately sent money to the family and arranged with Ricordi to publish an album of music to be sold for Piave’s benefit. In November 1868, the great Rossini died in Paris. Verdi suggested to his publisher that Italian composers write a Requiem Mass which would be performed once only in Bologna, the city where Rossini grew up, on the first anniversary of his death. A committee was set up to select the composers and assign them the various sections of the Mass. Eventually this was done, but the commemorative Mass was scuppered by political and religious intrigue in Bologna (where have we seen that combination before in Verdi’s life?). It was performed for the first time in Stuttgart in 1988!! Verdi’s contribution was the final movement, Libera me, which he later used in his Manzoni Requiem.

Despite these personal tragedies Verdi continued to search for possible operatic subjects; he worked on a revision of La forza del destino which was successfully produced at La Scala in February 1869. In September he received an invitation from the Khedive of Egypt to compose an ode to celebrate the opening of a new opera house in Cairo in November. Verdi refused, and the opera house opened instead with Rigoletto. But the Egyptians were persistent and by April of the following year Verdi agreed, in principal, to the anonymous scenario he had received from Paris. On Christmas Eve, 1871 Aida was performed for the first time at the Cairo Opera House. In February 1872 the opera was given at La Scala with an aria for the soprano added to the start of Act 3; an overture had been rehearsed but discarded. Grand Opera, a genre born and bred at the Paris Opéra, a genre which insisted on a historical basis for its plot and demanded lavish spectacle, ballets, massed choral scenes (and to which, I should add, Verdi contributed two examples) receives its apotheosis in Italian and in about half the running-time!

I promessi sposi, first published in 1827, is regarded as the greatest Italian novel of the 19th century; its author, Alessandro Manzoni, was as much a hero to those fighting for the unification of Italy as was Verdi. The composer greatly admired the author and, when he died, in 1873, Verdi determined to honor him in the only way he could: he composed a Requiem Mass. The first performance took place in the church of San Marco in Milan on the first anniversary of Manzoni’s death; three days later it was given a series of performances at La Scala. A tour of other European cities was arranged and the work was well-received, with a few exceptions. The Wagners, naturally enough, hated it; Hans von Bülow (Frau Wagner’s first husband) dismissed it in a German review, and was himself dismissed by no less than Johannes Brahms who said that any fool looking at the score would see that the composer was a genius.

To all intents and purposes Verdi was now retired. He still kept up with the opera world, particularly where his own operas were involved, usually complaining that it was all a mess. He still kept up with Italian politics, usually complaining that they, too, were all a mess! His domestic life was certainly a mess. Financial matters seemed to become very important to him and friendships that had survived over the years were abandoned because of a debt. In 1879 he wrote two short choral prayers. Around this time Giulio, the new head of the Ricordi firm, at dinner with Verdi and other friends brought the conversation around to Shakespeare and casually mentioned Othello. “I saw Verdi look sharply at me, with suspicion but with interest.” Giulio carefully nurtured that interest over the next years until, on February 5, 1887, Otello was rapturously received by the audience at La Scala. The immediate wonder of the score is that it was ever written: one’s late-70’s is not normally considered to be the age to embark on a musical setting of one of the most harrowing and volatile of all tragedies. Having acknowledged that wonder it is then possible to examine all the other wonders. A dear friend of mine, a conductor of even greater longevity (he is hanging up his baton next year at the age of 95!) said that Otello is the Bible of Italian Opera. It certainly sums up Verdi’s career, and, indeed, all the operatic progress made in the 19th-century.

But there was a circle to be rounded off. Verdi’s second opera had been a comedy, and, some forty years later, he felt he had found the right subject for a comic opera – Shakespeare’s Sir John Falstaff – and the right librettist – Arrigo Boito – to turn The Merry Wives of Windsor into a libretto. The result? The greatest opera of all. Some critics at La Scala on February 9, 1893, felt that the score lacked melody. What nonsense! In his late-70s Verdi still has so many melodies to give us that he doesn’t bother to develop them, so virtually every page has a melody which, in earlier years, would have been the basis for half an aria. Such melodic profligacy! Then there’s the musical characterizations. In the past the smaller roles were generic, and could be switched from opera to opera, or even within the same opera, with nobody noticing. Not here. Caius, Bardolph and Pistol are as carefully limned as Ford and Sir John, or Alice and Quickly. The instrumentation? What fairyland has ever sounded so delicately magical as the one Verdi conjures up in the final scene! I could go on!

In January 1897 Verdi suffered a stroke, but recovered remarkably well. Giuseppina had been ill all year and, on November 14, she died. Performances, and publication of the Pezzi sacri (the four religious prayers he had composed over the past years) occupied him, as did the construction of the Casa di Riposo, a home for retired musicians he was building in Milan. In December 1900 he went to Milan and was his usual self. On January 21 he suffered a stroke and the area around his hotel was quieted as best it could be: traffic was diverted; local carriages were ordered to move as slowly as possible; trams were forbidden to ring their bells; the hotel was closed to incoming guests. On January 27, Verdi died. Milan came to a standstill, as did the rest of Italy. Verdi’s will was strict in its instructions for a simple burial. But when, a month later, his body and that of his wife, were removed to the Casa di Riposo the world demonstrated its respect: some 300,000 people lined the route to the Casa; Italian parliamentarians, representatives of various governments, mayors, musicians made up the procession; Arturo Toscanini conducted the huge chorus in Va, pensiero. The unofficial national anthem of Italy – a country that didn’t exist when Verdi wrote it almost sixty years previously! If Verdi’s career as a musician, a politician, a man, is that of a “mediocrity”, then all I can say is “Viva mediocrity!”

Librettist Piave

Francesco Maria Piave, born in the Murano area of Venice in 1810, was the eldest son of a relatively well-off family involved in the manufacture of glass. When the business failed, Francesco, destined for the priesthood, had to leave the seminary and fend for himself. He wrote, and got a position as a proof-reader in a publishing house. After a few years of this he moved to Rome and it may have been there that he wrote his first libretto, Don Marzio, for a composer named Samuel Levi! The opera was never performed. He returned to Venice and his first job at the Teatro la Fenice (Venice’s principal opera house) was to complete Il duca d’Alba which Giovanni Peruzzini was unable to finish due to illness. Giovanni Pacini was the composer and the opera was first given in 1842, which was when the Fenice hired Piave as the resident “poet” (i.e. provider of librettos to composers commissioned to write for the theatre); he was also the “Stage Manager” – “Director” in today’s parlance. and as what we would now consider their “stage director.” The Fenice’s operatic reputation was second only to La Scala, so when Verdi received a letter of interest for an opera to be produced there, he was most anxious to accept the contract.

For his La Scala operas Merelli, the impressario, had given Verdi pre-written librettos. With the offer from Venice he was, for the first time, faced with the dilemma of finding an appropriate subject, always a complicated procedure with Verdi, and not made any easier by the censors. With two subjects already forbidden and others being bandied about, he received a letter from Piave, suggesting an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s play Cromwell. Verdi checked into this unknown writer and was assured by Mocenigo, the Fenice’s director, that he had good theatrical chops and knew the musical forms. Verdi agreed to use him. It turned out that his “theatrical chops” were not to Verdi’s high standards, even at this relatively early stage of his career. But Piave proved malleable, the very quality Verdi sought in a librettist. And so, over the next twenty years, Piave wrote a total of ten librettos for Verdi, including Ernani, Rigoletto, La Traviata, and La forza del destino. Verdi’s letters to Piave are filled with paragraphs about how to structure a scene in an opera; how to balance the dramatic needs with the musical ones; about the need for what he would later call parole scenica – “theatrical words” that would leap from stage to auditorium and grab the listener. Above all he was to be brief: in an opera the music carries far more emotional weight than does the text.

Often, when working on a Piave libretto, Verdi would summon the writer to Sant’Agata, where he could more easily bully him into supplying the needed situation or text. Despite the bullying, Piave became close friends with the composer as well as with Giuseppina Strepponi, who sometimes referred to him as Il grazioso (the Graceful One) on account of some of his archaically-worded verses.

In 1860, thanks, in large part, to Verdi’s influence, Piave became the resident poet and “Stage Manager” at La Scala, Milan. Seven years later, on his way to the theatre, he suffered a stroke. Both Verdis were devastated by the news. Giuseppina wisely forbade her husband to visit their friend: Piave, paralyzed and unable to communicate, would be horribly distraught. Verdi immediately sent money to his friend’s wife, and then badgered Ricordi to publish an album of piano pieces, the proceeds of which would go to the invalid. He died in 1869.

It’s easy to think of Piave as a one-composer librettist; but in fact he wrote almost forty librettos for a variety of composers. Scholars will recognize the names Saverio Mercadante and Giovanni Pacini. But Antonio Buzzolla, or Carlo Boniforti, or the Ricci brothers, Federico and Luigi? The Irish composer, Michael William Balfe, might ring a bell or two as the composer of The bohemian girl. There’s no doubt that the librettos he wrote for Verdi are his best, because Verdi demanded better, while lesser composers simply accepted whatever the librettist sent. But how sad that, for all his forty librettos, we know him today (if we know him at all) only as the author of a few Verdi operas. But such is the fate of the libretto-writer!

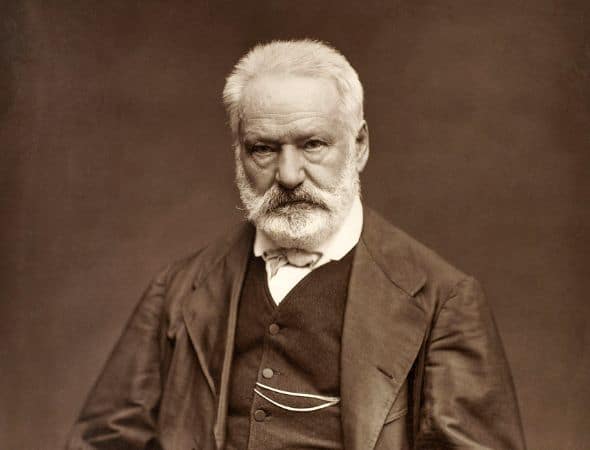

Writer Victor Hugo

Hands up those of you who’ve read read Notre Dame de Paris, published in Paris in 1831? I see. Now hands up those of you who’ve seen one of its movie adaptations? Tsk, tsk, tsk! The Hunchback of Notre-dame? Now that’s more like it! There’ve been about 10 movie versions since the first one in 1905. In 1923 Lon Chaney played Quasimodo, the hunchback; in 1939 it was Charles Laughton, with Maureen O’Hara as Esmerelda; in 1956 Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida starred; and in 1996 Disney released its animated film. There have been 4 adaptations for TV; 2 each for the stage and radio; 3 ballets; 4 operas; 6 musicals.

I’m guessing that many of you will have seen the musical Les Misérables, an adaptation a novel of the same name published in Paris in 1862. But before the musical conquered the world, there had already been 11 silent movie versions, while the “talkies” resulted in about 30 more productions from a variety of countries, including Egypt; Italy; Japan; Brazil; USSR (Soviet Russia to our younger readers!); Korea; Sri Lanka; Turkey; even a version in Hindi! There have been 5 adaptations for TV; 5 for radio; 6 stage versions; 7 animations; and, of course the musical.

Who wrote these wildly, and widely, successful novels? Victor-Marie Hugo did. He was born in 1802 in Besançon, and died in Paris in 1885; probably the most politically tumultuous span of years in all of French history. The Revolution, which erupted with the storming of the notorious Bastille prison in 1789, and included the Reign of Terror during which thousands of aristocrats, including the royal family, were guillotined, abolished the monarchy and established a Republic (the First) in 1792. That was when the rest of Europe decided that things in France had gone too far and the First Coalition declared war. Napoleon Bonaparte, a brilliant soldier, emerged as an inspired leader and defeated the various armies; the Coalition regrouped and a second war began in 1798. Fighting the rest of Europe again was, obviously, not occupation enough for Bony, for in 1799 he staged a coup d’état, and became First Consul; in 1804 he had himself declared Emperor. So now France is an Empire! And Beethoven violently scratched out the original dedication of his “Eroica” symphony! Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and subsequent banishment to St. Helena led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under Louis XVIII, the brother of the guillotined Louis XVI. Louis was succeeded, in 1824, by Charles X who was deposed in the “July Revolution” of 1830; his successor, Louis Philippe, was forced to abdicate in 1848, when the Second Republic was declared, with Prince Louis Napoleon as its President. Prince Louis declared himself Emperor Napoleon III in 1852, only to be deposed after France was defeated by Prussia in 1870, when the Third Republic was established, which lasted until the German conquest of France in 1940.

Hands up those who are (totally) confused by this? My hands shoot up!! Many a French mind must have been boggled, and many a tête must have been scratched! “Eh, Pierre, it’s Tuesday; are we a Monarchy, an Empire or a Republic, and if so, what number?” “Mon ami, France is like the weather: wait a day and it’ll all change!” Not surprisingly, Victor Hugo’s political thinking changed during his life: as a young man he had been in favor of the monarchy, but gradually turned to Republicanism. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1841 and in the same year King Louis-Philippe made him a Peer; in the Upper House he spoke against the death penalty, social injustice and censorship, while advocating a more Republican form of government. In 1851, when Louis Napoleon assumed power, Hugo denounced him as a traitor and left France, eventually settling in Guernsey, one of the Channel Islands, and refused to return, even under the amnesty granted in 1859. With the declaration of the Third Republic after the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, Hugo finally came home to France. His wife, Adèle, had died two years earlier; after his return to Paris his daughter, also Adèle, was committed to an insane asylum; his two sons died; and he himself suffered a mild stroke, while his mistress died in 1883. In his years of exile, younger writers like Flaubert and Zola, with their more “realistic” novels, had supplanted Hugo’s historical-fiction novels. But he hadn’t been forgotten: his 79th birthday, in 1881, was an extraordinary three-day event, culminating in a six-hour parade past his house while over 2 million people joined his funeral procession in 1885.

The huge international popularity of Notre-Dame de Paris and of the later Les Misérables tends to overshadow the fact that Hugo was writing, not just incredibly exciting page-turners, but novels with a social conscience: the settings might be in the past, but the injustice was contemporary. Charles Dickens proved an avid disciple, and Dostoevsky must surely have read The Last Day of a Condemned Man published in 1829. With such blockbuster novels available to us non-French in translation and adaptation, it’s easy to forget (if we ever were aware) that Hugo was a great poet whose first collection, published when he was 20, earned him a royal pension; further volumes appeared in 1829, 1831, 1835, 1837 and 1840. Many of these poems became songs. Liszt’s best songs to French texts are all settings of Hugo; Bizet’s greatest song is a Hugo poem; even Rachmaninoff and Wagner were inspired by his poems.

And then there were the plays: ten of them. His first play, Cromwell (1827), was turned into a libretto for Verdi by Piave when Venice wanted an opera from the young composer who had had such triumphs at Milan’s La Scala. Verdi was enthused neither by the subject nor by the novice librettist’s adaptation, but the proposal of Hugo’s Hernani as a substitute greatly enthused the composer. Hernani had been a riotous success when it was first performed in Paris in 1830. The riots were between the old-school, (who wanted preserved the Classicism of Racine and Corneille, with its regular verse; its avoidance of on-stage violence; its adherence to Aristotle’s “unities” ) and those who rejoiced in the romantic passion of Hugo’s characters (today we’d probably consider them a bit over the top), and the Shakespearean freedom to ignore a single location and have a heap of dead bodies on stage at the final curtain! Ernani was a riotous success in Venice in 1844. When the opera was produced in Paris two years later, Hugo, who had been opposed to the operaticization of his play in the first place, insisted that the title of the piece and the names of the characters be changed. They were.

Marion Delorme, written in 1829, was prohibited by the censor because it showed King Louis XIII (an ancestor of the reigning Charles X) in an unfavorable light and, therefore, might lead the public to have nasty feelings about the current king. “Current King” was removed in the 1830 Revolution, and the play was performed in 1831. In 1862 the great double-bass player, Giovanni Bottesini, wrote an opera based on the play; Amilcare Ponchielli’s operatic version was given in 1885.

Hugo’s next play, Le roi s’amuse, was officially closed down after its first performance in 1832. Since it is the basis for Rigoletto we’ll discuss it in another section. (SEE BACKGROUND LINK.)

The following year saw two plays produced. Lucrèce Borgia quickly became Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia, produced at La Scala in December of 1833, while Marie Tudor had to wait over 40 years before it was adapted (Arrigo Boito was one of the librettists!) and set to music by the Brazilian Carlos Gomez, who had wowed Italy with his 1870 opera Il Guarany. (Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda was based on Schiller, not Hugo). Angelo, tyran de padoue was produced in 1835. Two years later the play became Mercadante’s most successful opera, Il Giuramente. Today the play is remembered, if at all, as the basis for Amilcare Ponchielli’s most successful opera, La Gioconda, first produced in 1876; various revisions produced the version we see today on the rare occasions it’s put on. Compared to Verdi (Aida was first produced in 1871) Ponchielli may seem clunky and clumsy, but there’s a sort of visceral vocal energy to Gioconda that almost by-passes Verdi and takes us straight to Puccini-Mascagni-Leoncavallo-land and verismo. Ponchielli’s librettist was Tobia Gorria, an anagram for Arrigo Boito, a composer in his own right, but who is more famous today as the instigator and librettist for Verdi’s last operas: Otello and Falstaff.

In 1836 La Esméralda was given at the Paris Opéra, with music by Louise Bertin, and libretto by Victor Hugo, adapted from his Notre-Dame de Paris. It limped along for five performances.

Ruy Blas (1838) resulted in an Overture by Mendelssohn who, apparently, hated the play (but the music is fun!); a parody by W.S. Gilbert (of GilbertandSullivan fame). An opera by one Filippo Marchetti died in childbirth at La Scala in 1869, which only goes to show that even Opera Central screws up sometimes, and that for every Verdi there are hundreds of Marchettis!

Hugo’s last plays, Les Burgaves from 1843, and Torquemada from 1882, seem not to have interested musicians.

It’s difficult to arrive at an accurate tally of the musical works inspired by Hugo’s writings – one source mentioned “well over one thousand”; probably most of them are songs. But composers continue to mine his works: the Alagna brothers (Roberto is the tenor in the family) made an opera from his 1829 novel protesting capital punishment, Le dernier jour d’un condamné (The last day of a condemned man). Frédérico wrote the libretto and David composed the score for his tenor brother; it was first performed in Paris in 2007, and recorded. And if the Alagna brothers, in the 21st-century, can see musical possibilities in Hugo’s writings, who knows what other composers will find there! But even if there are no further translations of Hugo’s words into music, we music-lovers already have a treasure-chest filled with masterpieces by such a diverse group as Liszt, Fauré, Bizet, Wagner, Rachmaninov and Verdi.