The Reality of "Verismo"

The individual successes of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci in German opera houses prompted German critics to wonder what was going on in the world of Italian opera. Italian critics, some 5 years after those operas’ premieres, felt compelled to come up with a term which might define those works. Which was, you guessed it, verismo.

But what, exactly, is verismo? Dear Opera Lover, allow me to let you into a secret: the various critics/scholars who came up with the term apparently didn’t know, since there isn’t a definitive definition! And you should know that later critics/scholars seem to not know either! All are agreed on two things only:

- the term derives from a literary movement towards “realism,” which began with the novels of the French writer, Émile Zola (1840 – 1902), whose works influenced a number of young Italian authors; and,

- this resulted in operatic librettos dealing with the lives and loves and passions of folk more lowly than those of the Kings and Queens and Counts and Ladies-in-Waiting, who had previously populated the Italian operatic stage.

Which resulted in—well— just Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci. Despite other composers’ attempts, including one by Jules Massenet (the very successful composer of Manon and Werther) to emulate Mascagni’s success, they miserably failed. So we’re left with Cav and Pag. Two operas, dear Opera Lover, do not an operatic genre make!

The word itself derives from verità, which means “truth,” which would align it with that literary trend towards “realism”; but it’s worth bearing in mind that one source I consulted equated verismo with brutalità and crudezza (which need no translation), before adding naturalismo and realismo (which also need no translation).

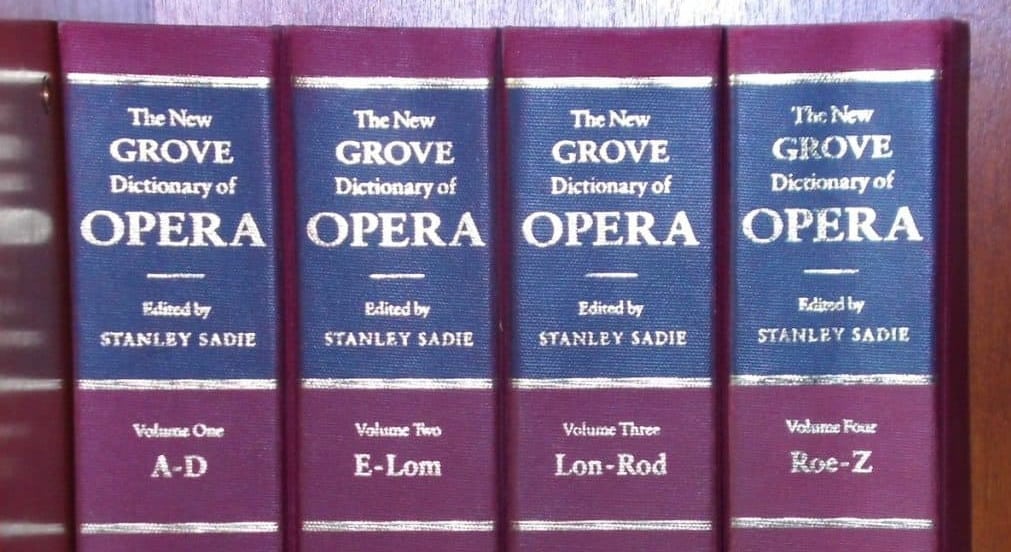

The generally-recognized standard English-language musical encyclopedia is A Dictionary of Music and Musicians by George Grove, whose first volume was published in 1879; 3 further volumes appeared over the next decade. Over the years it has been revised and expanded; its original author has replaced the original indefinite article “A,” so it’s now published as Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

Its most recent article on verismo notes that in its literary origins there was “a markedly regional character,” as well as “an interest in the lower social strata” in their works. Certainly, that is true of Mascagni’s Cav, which operatically adapts Giovanni Verga’s dramatized version of his original short story with the same title. The details of its plot need not concern us here, except to note that it deals with an unmarried and pregnant peasant girl in a Sicilian, and therefore very Catholic, village: definitely “regional” and “lower social strata”!

But then Grove seems to contradict itself. Referring to Cav, we read “The libretto preserved the vivid dialogue and the rapid pace [of Verga’s “Cavalleria Rusticana”] but the operatic version was distanced from the veristic play by…a dilution of its down-to-earth language with traditional high-flown libretto jargon.” Oops! Either Verga’s “vivid dialogue” is “preserved” in the libretto, or “its down-to-earth language” is diluted “with traditional high-flown libretto jargon.” A scholarly article can’t have it both ways!

Grove’s mention of the language of a verismo libretto is worth considering. Standard 19th– century Italian librettos favored poetic-sounding words over the real ones: occhi (eyes), for example, were lumi (“lights”). Religious censorship at the time prohibited the use of many words with Catholic connotations: in Rigoletto, for instance, Gilda sings of going to a tempio (“temple”) rather than to a chiesa (“church”). And the strict political censorship would forbid the portrayal of a King as a sexual predator, so, in Verdi’s adaptation of Victor Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse, the French King Francis I became the Duke of Mantua in Verdi’s Rigoletto. Some years later that same censorship, disallowing anything that might hint at the assassination of a King, or of a plot to kill him, let alone his actual murder on-stage, forced Verdi, in Un ballo in maschera, to demote the historically assassinated King Gustave III of Sweden to a fictional Governor of Colonial-Era in Boston – which must have furrowed as many Roman brows when the opera premiered there in 1859 as it does today; though the trend in contemporary productions is to restore as much of the Swedish original as possible – and much of it is! Some of you may remember Utah Opera’s production of the opera in 1992, which relocated the Boston setting to New Orleans, which actually made more dramatic sense!

We English-speakers expect a poetic line to contain a certain number of alternating stressed and unstressed syllables; ta-DUM-ta-DUM-ta-DUM-ta-DUM-ta-DUM, for example, represents Shakespeare’s Iambic Pentameter, where five stressed syllables are each preceded by an unstressed one. Italian librettos were, however, governed by the number of syllables in a line, regardless of stress: the text of the slow part of an aria, for instance, would have a prescribed number of syllables per line, while the faster section would have a different syllable-count.

But by the mid-1860’s Verdi was encouraging Antonio Ghislanozi to give him a more “realistic” text for Aida: he wanted words which would leap across the orchestral divide between stage and audience to grab the listener’s attention: parola scenica (“theatrical text”) he wanted, and he didn’t care whether or not that text would fit into a specific syllabic count. Much of the final duet between Aida and Radames, interestingly, is Verdi’s own, written without concern for either rhyme or syllabic count.

With Arrigo Boito, Verdi found a kindred spirit. The librettist of Otello and Falstaff was not interested in those old syllable-governed forms. (Though it must be admitted that his choice of obscure language in parts of his texts sometimes made them more incomprehensible than the convolutions of sentence-structure in which the older syllabic-count had resulted.) But post-Boito librettists, especially Puccini’s Illica and Giscosa, would use his rejection of the traditional syllabically-controlled lines to write texts which were more conversational and colloquial–more “realistic.”

The Unification of Italy in 1871, establishing the Kingdom of Italy, got rid of the strict political and religious censorship which had plagued earlier librettists. If, as Grove’s article implies, Mascagni’s librettists (Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti and Guido Menasci) were not aware they had that more “realistic” freedom—though they did have Turridu ask Santuzza if she were going to chiesa (“church”), rather than the pre-Unification generic tempio (‘temple”), which Verdi had had to accept in Rigoletto (see a few paragraphs above!)—Leoncavallo laced his libretto of Pag with an abundance, according to an article by Matteo Sansone, of “oaths and insults” which would never have been allowed in the pre-Kingdom years. Some examples (and assume an exclamation point after each of them!): Per la Madonna (“By Mary – the mother of Jesus”); Per la croce di Dio (“By God’s cross”); Sgualdrino (“Tramp”); Meretrice abbietta (“Wretched whore”).

Grove’s article tells us we should expect to hear “[p]opular songs…drinking songs…religious hymns.” And Cav supplies them! Its orchestral introduction is interrupted by the voice of Turridu, singing a folk-song-like “aubade” (usually sung in Sicilian dialect) to Lola, his current mistress. Later on, Mascagni gives us a huge choral celebration of Easter Sunday, complete with off-stage organ and church choir. After Mass, we are treated to a drinking song from our tenor, before he is killed in an off-stage duel. Everything Grove’s article tells us what to expect!

Except!

Pagliacci gives us little of that. OK, its plot concerns a troupe of strolling players who show up in a village in the Calabria region of Italy; and OK, it takes place on August 15, the Catholic Feast of the Assumption, celebrating Mary’s arrival in Heaven. But the closest Leoncavallo comes to “religious hymns” is the chorus greeting the arrival of the local bag-pipers, to lead the parishioners to Church for Vespers, and you should note that what they sing is not “religious.” There are no “songs” – popular or drinking – though Beppe, as Arlecchino in the “play” that is performed, does sing a serenade to his lover Colombina.

Verismo, we are told, showed “an interest in the lower social strata,” which is true, as far as it goes, but isn’t very far, when you come to think about it. Yes, Cav/Pag has not a King/Queen/Noble/Lady in sight, as opposed to those upper-class folk who populated 19th-century operas, not to mention the gods and goddesses of even earlier operas. But to suggest that pre-Cav operas ignored “lower social strata” is to forget, for instance, Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, whose principal characters are the servants Figaro and Susanna; and it is to forget, in Don Giovanni, not only the peasants Zerlina and Masetto, but, more importantly, Leperello, Giovanni’s servant, and, in Act 2, his substitute. And it is to forget all those lower-class folk (essentially everyone except Nero; his wife Ottavia; and maybe his future wife Poppea) in Monteverdi’s mid-1640’s L’incoronazione di Poppea. Rigoletto and his daughter Gilda (not to mention the murderer Sparafucile and his sister Maddalena) are not in the same social class as anyone else in Verdi’s Rigoletto; and surely that opera is more concerned with those “lower social strata” characters than with the Duke and the virtually anonymous group of sycophantic courtiers who surround him!

One might argue that pre-verismo operas, despite those various “lower social class” characters, had not concerned themselves with the members of the kind of tight-knit village community we see in Cav. But Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (1832), is set in a “small village” whose entire population is discombobulated by the almost simultaneous arrivals of a military man in search of recruits, and a fake salesman in search of rubes; since it’s a comedy, the opera ends happily with tenor and soprano united, and with the community of villagers restored to their previously un-combobulated lives. Verdi’s Falstaff (1893) takes place in the very “middle-class” society of the London suburb of Windsor, where everyone not only knows their neighbors but also their neighbors’ business! And while John Falstaff may be a “Sir,” he ain’t the kind of “noble” as is, for example, the Count di Luna in Il Trovatore.

Then Grove’s definition tells us of “violent vocal outbursts, heavy orchestration, big unison climaxes, agitated duets and mellifluous intermezzos…” in verismo. Listen, dear Opera Lover, to your recordings of Cav; or watch performances of it on Youtube. Certainly, the duets between Santuzza and Turidu and between Santuzza and Alfio are examples of “violent vocal outbursts.” But listen also to Verdi’s Otello, during which the title character, under the influence of Iago’s suggestions that his wife, Desdemona, has been unfaithful, becomes more and more enraged, especially in his duets with Iago; and surely there isn’t a more “violent vocal outburst[s]” than the one in which he publically throws her to the ground.

For Grove to include “heavy orchestration” as an element of verismo seems to ignore the operas of Wagner. Yes, those Santuzza/Turridu and Santuzza/Alfio duets climax with the orchestra playing the same “chune” the singers are singing; but much of Isolde’s final aria in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde has the orchestra play along with the singer. And Wagner’s orchestra is huger than Mascagni’s! And don’t tell me that the orchestra accompanying Brünnnhilde’s so-called “Immolation Scene,” which ends Götterdämmerung, is anything but “heavy”!

Pre-Cav operas contained many “agitated duets.” And you can take your pick of them! The conversation between Donna Anna and Don Ottavio, before her “Or sai chi l’omore” aria in Mozart’s Don Giovani; the recitatives between Macbeth and his Lady in Verdi’s opera; those between Norma and Adalgesa in Bellini’s opera; between Leonora and di Luna in Il Trovatore; between Violetta and Alfredo (Act 1) and Violetta and Germont (Act 2) in La Traviata. And you realize there were many of them long before Cav.

Neither were “big unison climaxes” unknown. Verdi, again, provides examples. Some of you may remember Utah Opera’s productions of his Macbeth in 1994 and in 2009: the huge ensemble that ends Act 1 has everyone singing the melody. Same thing at the end of Act 2 in La Traviata. And let’s not forget his “unison” choruses: “Va, pensiero” from Nabucco, or the so-called “Anvil Chorus” at the start of Act 2 of Il Trovatore.

Which leaves us with “mellifluous intermezzos.” And here Mascagni’s Cav did start a trend, though it was short-lived: Leoncavallo’s Pag, from two years later, is divided into 2 acts, but his orchestral introduction to the second act is titled “Intermezzo”; while Puccini provided an “Intermezzo” between the second and third acts of his Manon Lescaut (1893).

One has to wonder whether Grove’s article on verismo was not based solely on Mascagni’s Cav. Earlier I said that “two operas do not a genre make,” but now it seems we’re reduced to one since little in Pag fits its definition.

But that’s OK since it makes us question “Grove’s” authority. And by such questioning we’ve learned that, instead of being the explosion of a new genre onto the Italian operatic stage, as the original Italian critics/defenders would have us believe, Cav/Pag was the result of a gradual transition, over many years, from a highly-stylized literary-musical form of writing to something which allowed librettists to provide composers with texts which were more “natural,” more “real.”

What about Italian opera after the Cav/Pag phenomenon died down?

The Irish-born George Bernard Shaw, before he became a great playwright, had been an astute, and often-times devastating, critic of London’s musical scene in the early 1890s. His initial reaction to the music of Cav was not exactly positive: “…it is a youthfully vigorous piece of work, with abundant snatches of melody broken obstreperously off on one dramatic pretext or other…The people who say, on the strength of it, that Verdi has found a successor…would really say anything. Mascagni has shewn nothing of the originality or distinction which would entitle him to such a comparison.” A week later he wrote: “Of the music of Cavalleria…I have already intimated that it is only what might reasonably be expected from a clever and spirited member of a generation which has Wagner, Gounod, and Verdi at its fingers’ ends, and which can demand, and obtain, larger instrumental resources for a ballet than Mozart had at his disposal for his greatest operas and symphonies.”

And then, in 1894, came to London Giacomo Puccini’s Manon Lescaut. “Italian opera,” Shaw wrote, “has been born again…Puccini looks to me more like the heir of Verdi than any of his rivals.”

And Shaw, as he so often was, was right.

It was Puccini who, more successfully than any of his contemporaries, combined the traditional Italian emphasis on the voice as the essential conveyor of emotion in opera with the demands of the post-Boito more natural and freer-style libretto. He also continued to develop Verdi’s example of making the orchestra an integral element of the drama, while, mostly, ensuring it was subservient to the voice; acknowledging Wagner (as did Verdi); and keeping an ear open to what was happening elsewhere, which mostly meant France, where Debussy was revolutionizing the sounds and colors an orchestra might produce in such works as Prélude à l’apès-midi d’un faune (1894); La Mer (1903-1905); and the operatic earthquake that was Pelléas et Mélisande, in 1902.

Puccini gave verismo a musical legitimacy it had not previously had, simply because he was a far better composer than either Mascagni or Leoncavallo.

La Bohème (1896) with its cast of struggling artists and its heroine destined to die of consumption, certainly conforms to Grove’s interest in “lower social strata,” and the libretto is filled with colloquialisms. Musetta’s aria in Act 2 nods to the notion of “popular song.” The finale of Act 2 might squeak by in the “big unison climaxes” category. Certainly, the duet in Act 3 between Mimì and Marcello would qualify as “agitated.” But there’s nothing of crudezza nor brutalità here.

Both of which abound in Tosca (1900). and ironically it is Baron Scarpia, the only “noble” member of the cast, who embodies them. To seduce the former peasant and now operatic diva, he, the Roman Chief of Police, has had her lover arrested and tortured as a bargaining tool. The torture is vividly described, verbally and musically. Realizing that the only way she can save her lover’s life is submission to Scarpia’s sexual advances, his attempted rape is thwarted by Tosca’s grabbing a knife and stabbing him to death. In the final act, her lover is really shot by a firing-squad Tosca believed was fake; realizing her mistake, she jumps off the top of the Castel Sant’Angelo. Brutal torture; attempted rape; 2 murders; and a suicide; surely these must give Puccini’s opera a very high ranking on the verismo scale.

Perhaps the finest example of verismo is Puccini’s Il Tabarro: the first of his Trittico sequence of his one-acters which was first given at the Met in 1918. Michele is a bargeman in 1890s Paris; Giorgetta, his younger wife, is having an affair with Luigi, one of the stevedores. The rest of the cast includes other stevedores and one of their wives; someone selling printed copies of songs, singing his wares; an organ grinder churning out popular songs; 6 young dressmakers; and two off-stage lovers. Definitely “lower social strata.” Realizing his wife’s adultery, and with whom, Michele kills Luigi; he covers the body with his cloak and then, savagely, invites his wife to see what is hiding under his tabarro.

“Verismo is misleading and inadequate as a term for turn-of-the-century Italian opera,” says Grove’s, and finally gets it right! But, in getting it right, Grove’s gets it wrong! For it is “misleading” to define a so-called genre based on only one opera (maybe two); and it is “inadequate” to cite operatic failures or rarely-revived operas, in support of its argument.

Verismo? There is no satisfactory definition!

So just enjoy the drama the music gives us–or vice versa!