Carmen: The Musical Story – Act 1

CARMEN: THE MUSICAL STORY

Prelude and Act 1

Bizet’s orchestra for Carmen is not a large one for the 1870s, but probably corresponds to what was available to him at the Opéra Comique: 2 Flutes (each of which double Piccolo; 2 Oboes (2nd oboe doubles on English Horn); 2 clarinets (in A and Bb); 2 Bassoons; 4 Horns; 2 Trumpets (in A and Bb); 3 Trombones; 2 Harps; Timpani; Triangle; Cymbals; Bass Drum; Snare Drum; Castanets; Tambourine; Strings.

The audience at the Opéra-Comique on March 3, 1875, might have been expecting an Overture to start off the evening. Instead, Bizet gave them a Prelude. It’s noisy enough and its A major tonality is certainly bright enough to dampen any audience chatter! And its opening theme will return in the final act to introduce the parade of dignitaries entering the bull-ring. Abruptly the music shifts tonality and over brass pulses, the strings play a swaggering tune that will become the refrain of Escamillo’s aria in Act 2. The opening music returns and finishes in bright A major. A measure of silence. Strings shudder a D-minor chord: an ominous sound since at least Mozart’s Don Giovanni or the opening bars of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. A clarinet, a bassoon, a trumpet and the cellos announce a melody that will assume the importance of a Wagnerian “motif”; and since it does, it has been called “Fate.” This theme grows in intensity until it is cut off by a sharp discord. Silence.

The curtain rises to a lazy pulsing monotone from low strings. The answering flutes and clarinets do nothing to dispel the atmosphere of draining heat After 19 bars of repeated Fs we seem to be heading for a regular harmonic close – think of the ending of “The Star-Spangled Banner” – but Bizet won’t allow that, and the resulting discord (actually two, for against the soldiers’ F, cellos and basses play a G# while flutes slide on to the F from the upper note G) unsettles us. Even when the soldiers seem to be coming home harmonically, Bizet side-steps for a couple of bars. Again, unsettling. Maybe they know that this placid scene could quickly turn dangerous. The soldiers observe the oddities of the citizens strolling around the square; Moralès, their commander, tells us that his men, while seemingly taking it easy smoking and chatting among themselves outside the Guardhouse, always keep one eye on the crowd.

The rhythm of Moralès leads us into another key and a faster tempo: Moralès is obviously excited by the appearance of a young girl who seems to want to talk to them. Note that the music stops before he asks her what she’s looking for, which allows the audience to hear the text. Bits of melodies appear as she asks if they know Don José; Moralès proves, in a descending line, very courteous, though he quickly launches into a jaunty tune and promises the imminent arrival of José. With slimy triplets he invites her to stay with them in the guard-house until José arrives when the guard changes. She refuses, despite his promise (again slimy triplets) that she need have no fear. Playfully she adopts Moralès’s jaunty tune to tell them she’ll come back later. The stage direction notes that the soldiers surround her, insisting that she stay – what did I say about things quickly turning dangerous? Strings and winds indicate her escape. Maybe now we’re on a more secure harmonic base? No – listen to those half-steps in the cellos and basses! Moralès suggests that, since “the bird has flown,” they might as well resume checking out the people in the square; which they do.

An off-stage trumpet fanfare is answered by one from the Guardhouse. While the soldiers line up, a march is heard off-stage. Led, according to the Meilhac/Halévy libretto, by two bugles and two fifes (Bizet settles for two flutes with trumpet additions at the end of phrases), the new troops arrive; behind them comes a group of kids (aussi petits que possible: as small as possible) who must take long strides to keep up with the soldiers; they are followed by Lieutenant Zuniga and Brigadier Don José; behind them are the Dragoons with their lances.

Photo: Kent Miles

The kids sing of their delight in mimicking soldiers with heads high, shoulders back and chests forward; but mostly they echo a trumpet call. Moralès tells José that a pretty young girl in a blue skirt and with her hair in plaits came looking for him. “It must have been Micaela.” In the dialogue version this short conversation is underscored by a canon in the orchestra: a solo violin begins a variation of the kids’ melody, followed two measures later by a solo cello playing exactly the same thing; the rest of the strings just have pizzicato chords. The trumpet fanfare resumes and the “old Guard” marches off, accompanied by the kids. Note the scurrying string figures in the orchestral playout!

The dialogue which now follows between Lieutenant Zuniga and José was greatly abbreviated for the recitative version, but it contains some very valuable information. The Lieutenant is curious about things, he tells José, because he has been with the regiment for only two days, and is a new-comer to Seville. That large building, José tells him, is a tobacco-factory; the four or five hundred who work there are on their lunch-break, but José assures Zuniga that quite a crowd will gather to watch them returning. Men are not allowed into the factory because, since it’s hot inside, the employees strip off as much clothing as possible. Zuniga is intrigued: “Are they pretty?” José admits he hasn’t taken much notice because Andalusian girls scare him. He’s more interested in the girl who enquired after him earlier, teases Zuniga. The blue skirt and plaits are typical of Basque girls, José explains. His family name, Lizzarabengoa, is a very old Christian one; he entered a seminary, but was more interested in the Basque sport of Pelota than in his studies. After beating one of his fellow-students, the loser picked a fight with him; bad idea! José had to leave the country (Basque Country was independent then) and joined the army in Seville; his mother, with the adopted Micaëla, moved outside of the city, to be closer to him.

The factory bell ends their conversation. José sits apart, working on his rifle. To twenty bars of an excited orchestral introduction, the stage fills with the young men who have come to gawk at, and flirt with (if they can) the returning factory girls. Their brief chorus ends in C major and a moment of silence. Rippling muted violins and cellos accompany a flute and clarinet playing a slower, more languorous version of the melody we heard at the start of the number. They are joined by an oboe and bassoon and finally by the first violins. As all the violins and violas float down, listen to the wisp of melody in the cellos and bassoon. Pure aural magic!

And all to introduce the factory workers (i.e. the Female Chorus) who are (GASP!) smoking! And then they sing of their joy in it (HORRORS)!! They compare the words and protestations of lovers to smoke which disappears into the sky. Whatever your personal opinion on smoking might be, you’ll have to admit that if inhaling tobacco inspired one of the most beautiful choruses in all opera, there must be one good thing about it! There is one other opera I know of that demands smoking. The secret in Wolf-Ferrari’s delightful one-act opera Il Segreto di Susanna is Susanna’s smoking, and she does light up a cigarette before singing her big aria! (And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll take a cigarette-break before continuing.)

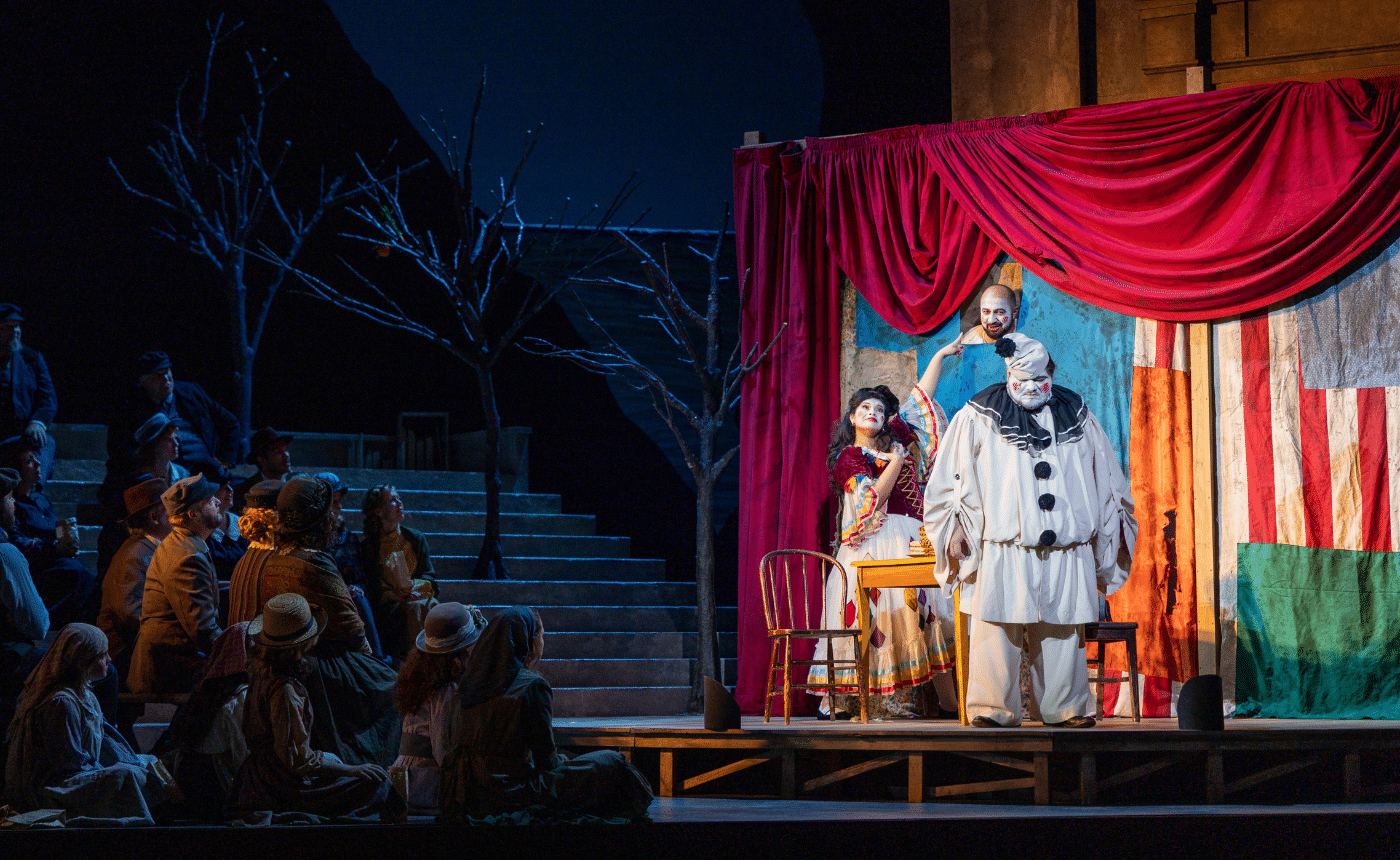

The music changes to a rather violent ascending figure. Where, wonder the basses, is Carmencita? To a concentrated, and faster, version of the “Fate” theme we heard in the Prelude, the tenors notice her, and then all the men announce her arrival. The tenors surround her, begging for her attention: Tell us when you will love us! I don’t know, she answers: maybe (minor key = sad) never; maybe (major key = happy) tomorrow; fragment of “Fate,” but certainly not today!

Cellos in D minor (the key of the first statement of the “Fate” theme) begin a rhythmic figure we associate with the Tango; which, though it stops at cadence-points at the ends of verses, never changes throughout the 120 measures that make up the “Habanera”. (Bizet had earlier used this kind of obsessive repetitive rhythmic accompaniment in one of his greatest songs: Les adieux de l’hôtesse arabe – check out Joyce di Donato on youtube!) This is the first of three “fake-folk” numbers that Carmen sings: later in this act she will sing a “Seguidilla” and she begins the second act with a “Gypsy Song.” You could say, and I have said to assorted mezzos (who didn’t take it kindly) that Carmen doesn’t really sing, in operatic terms, until the duet with José half-way through the second act. The text of the song was developed, after much agonizing (read “The Writing of Carmen” chapter), from Mérimée’s “…acting as women and cats usually do, refusing to come when they are called, but coming when they are not called…” In the opera it’s love that is a bird which won’t be tamed; it comes and goes as it pleases, so be warned! When the ladies repeat Carmen’s words they sing in D major (the tonic major, if you know theory!), and what a difference F# makes! The melody becomes almost playful, as if to say that love is a game to be enjoyed, contradicting Carmen’s warning.

The tenors, not at all discouraged, beg Carmen, with bits of “Fate” from the violins interrupting them, to answer their pleas. Orchestral “Fate” takes over as Carmen notices the oblivious José but this time the theme ends on a question. In the original libretto she asks him what he is doing and then makes fun of his response; in the “recitative” version she says nothing. The important thing is that she throws an acacia blossom at him (ideally, it hits him between the eyes) before she runs off into the factory, leaving him to be teased by the women who repeat the warning, and the music, of the “Habanera,” before they return to work. An impassioned orchestra postlude, with hints of “Fate,” empties the stage and leaves José alone.

In dialogue and recitative he is shocked by what she did – remember he told Zuniga that Andalusian women scared him; here the librettists actually use Mérimée’s line about women and cats. He picks up the flower, inhales its intense perfume and notes that if there are witches, Carmen must be one.

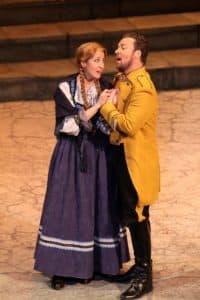

Micaëla reappears. “Mr. Brigadier?” José quickly hides the flower in his tunic. “Your mother sent me,” and their duet begins. She brings him first, she tells him, a letter from his mother; then there’s some money to supplement his pay; the third thing is more valuable than money – actually, for a son, it is priceless, but she is reluctant to give it, yet. Then she launches into how her trip to Seville happened. They had just left church (an aptly religious-y few bars) when, to more playful music, Mother suggests Micaëla should set off for the city – it’s not too far – and find my son. Tell him (this to a gorgeous melody which you should remember because it will return in Act 3!) that I dream of him night and day, that I am full of hope and that I forgive him; and give him this kiss from me. As Micaëla kisses José, the strings take over, not only rounding out the phrase, but also ushering in the next section of the duet. José sees in his mind’s eye, not just his mother, but his early life; sweet memories flood back, filling him with strength and courage. Micaëla joins him with the same text (though she changes the pronouns): listen to the final phrase which takes the voices from high to low and back up again – lovely. Ominous warning notes from the horns and then from a trumpet and trombone while a condensed “Fate” skitters down through winds and strings. José, staring at the cigarette factory, wonders what kind of devil has singled him out; but even from afar his mother protects him and the kiss she has sent averts the danger and saves her son. He ignores Micaëla’s confusion and asks when she returns home. This evening: tomorrow I will see your mother. Then (to the melody you need to remember) tell her that her son loves her, is sorry for what happened and give her this kiss from me. Micaëla promises. And we are treated to a musical repeat of his memories, which we’re very happy to hear. But listen to what Bizet adds to what should have been the final cadence: twenty-three bars of intertwining voices whose phrases sound like a dreamy memory of what we’ve already heard, followed by a magical final few bars for the orchestra.

Photo: Kent Miles

In the original libretto José reads aloud his mother’s letter, which contains a very pointed reference to his eventual return home to marry Micaëla. Hearing this, she suddenly remembers errands she must run and says she’ll come back for his written reply before she leaves the city. He continues reading after she leaves, and promises he will marry Micaëla. “And as for that gypsy with her magical flowers…[Just as he starts to take the flower from his tunic, huge noise from inside the factory.]” The recitative version has her leave immediately and the letter is read silently, while the strings play that theme you’re supposed to remember; he promises to marry Micaëla and just as he is about to curse the evil witch who threw a flower at him, chaos from the factory interrupts him.

The women rush out screaming for help. Apparently Carmen and Manuelita got into an argument which led to physical assault, and they are divided as to who struck the first blow. Zuniga orders José to take two soldiers and investigate the disturbance. Eventually the women are calmed down and Carmen is led out of the factory by José and the two soldiers. The recitative account is very bland: “There was a fight; one women was injured by this woman.” José’s dialogue is much more vivid, and much more frightening: “First I saw about three hundred women screaming and making such a racket that would drown out thunder. On one side there was a woman, arms and legs in the air, screaming for a priest, thinking she was dying. On her face was an X, cut with two slices of a knife. Opposite her I saw,” and here, interestingly, he hesitates before he says “Carmen.” Did she say anything then? Nothing. Carmen says she was provoked and acted only to defend herself, right Brigadier? After a moment’s hesitation José says that he gathered that the argument between the ladies got more heated and that she, with the knife she used to cut cigars, used it on the face of her fellow-worker. It was clear to me, and I arrested her; initially she resisted, but then followed me “like a lamb.”

Zuniga begins his interrogation which is so much more musically effective in the original version, where he speaks and she sings. A solo viola sustains the note E. Carmen’s response, with two violins joining the viola, is an impudent “Tra la la; no matter what you do to me I’ll say nothing.” A flute in its low register underscores his next statement. Again, “Tra la la” from Carmen. Zuniga asks José (now with the flute in its more usual register) if he is sure he has arrested the right woman. This prompts an outburst from some of the women (cellos and basses begin a theme we’ll hear later); Carmen tries to attack a woman closest to her, but is restrained by José. Zuniga calls for a rope and orders José to tie her hands; smiling, she holds them out to José, with more “Tra la la-ing.” Zuniga tells her she’ll be brought to prison where she can sing her gypsy songs to the jailer; he leaves to write out the order. The number ends with two echoes of “Fate.”

All of this is much abbreviated in recitative; much earlier in the sequence Zuniga tells Carmen she can sing her songs in prison, prompting an outburst from the women: “En prison!” They are herded back inside the factory, Zuniga leaves to write the order and the two are left alone.

Carmen starts to use her wiles on José. What will become of me in prison! You are so kind. This rope is too tight, it’s hurting me. José unties her hands. If you let me escape I’ll give you a magic stone. He remembers who he is: You’re going to prison and there’s nothing you can do. Then Carmen claims she was born near his birthplace and was abducted by gypsies; she only works in the factory to earn enough money to go home to look after her mother. He’s not taken in by this: everything about you says you’re a gypsy. It’s true, she answers, but it’s very good of me to have gone to the trouble of lying to you! Anyway, you’ll do what I say because you love me; that flower…the spell has worked. This angers José: I forbid you to speak to me. OK I won’t speak.

Instead she sings. Another folk song: a Seguidilla, which is a Spanish dance in triple time. She sings of the place run by her friend Lillas Pastia, where she goes to dance and drink wine. But it’s not much fun by yourself, especially at the weekend. José again tells her not to speak. I didn’t speak; I was just singing to myself; and thinking; I’m not forbidden to think. I’m thinking of a certain officer who loves me, and I could probably love him, even though he’s only a brigadier. The music begins in a playful, dancing mood, but notice how Bizet, by slowing it down and altering the harmonies and accompaniment, turns it into something more insinuating and seductive. José is smitten. If I agree, you’ll keep your promise – if I love you, you’ll love me? Of course! Which leads to a triumphant repeat of the opening verse, ending on a brilliant high note.

We don’t expect a fugue – that very-learned form of composition favored by J.S. Bach and a feature of grand choral works of a religious nature – to figure in a mid-nineteenth century opera about a freedom-loving, amoral gypsy. But that’s what the orchestra begins. In the dialogue-version we would have heard the opening three bars in the “Interrogation Scene.” Muted cellos introduce the “subject,” followed, eight bars later, by muted violas taking it over. Zuniga appears with the order: “Keep a careful watch on her!” The crowd, including the soldiers and the factory women, reassembles. Carmen whispers to José: “I’ll push you as hard as I can; fall, and leave the rest to me.” Cheekily she sings to Zuniga the Habanera’s refrain; winds whisper a variant of the verse which comes to a sudden stop on a timpani roll. Carmen pushes José, he falls, and she makes her escape to the great delight of the crowd while the orchestra thunders out the fugue subject as the curtain falls.

What an act! What variety – of music, of sounds, of dramatic action! By Wagnerian standards it’s not long (the first acts of Götterdämmerung and of Parsifal clock in at around two hours), but it was certainly longer than the audience at the Opéra-Comique was expecting on the evening of March 3, 1875; which prompted Bizet to make some cuts after the opening; these are discussed in the “Writing and Rehearsing” section.

©Paul Dorgan