Norma Online Course by Dr. Paul DorganPart 3: THE MUSICAL STORY OF NORMA – ACT 1

*Note: All video excerpts are drawn from a 1978 performance of Norma for The Australian Opera, featuring Joan Sutherland in the title role.

Norma was given its first performance at Milan’s La Scala on December 26, 1831. The libretto, by Bellini’s regular librettist Felice Romani, was based on the very recent (premiered in 1831!) French play Norma, ou L’infanticide (Norma, or the Child-killer) by Alexandre Soumet (1786 – 1845). Here is the opera’s cast:

Norma, (High Priestess of the Druids) – Soprano

Adalgisa, (Vestal Virgin) – Soprano

Clotilde, (Norma’s confidante) – Mezzo-soprano

Pollione, (Roman Proconsul in Gaul) – Tenor

Flavio, (A Centurion, and friend to Pollione) – Tenor

Oroveso, (Archdruid and Norma’s father) – Bass

Two children, (whose parents are Norma and Pollione) – Silent

Druids; Bards; Priestesses; Warriors of Gaul – Chorus

The action takes place in Gaul during the Roman occupation (around 1 B.C.) in the sacred woods of the Druids and the Temple of Irminsul, the Gallic God of War.

Bellini’s orchestra is typical of its time. 2 Flutes (the second doubling Piccolo); 2 Oboes; 2 Clarinets; 2 Bassoons; 4 Horns; 2 Trumpets; 3 Trombones; Cimbasso (an early version of the bass-trombone); Timpani; Bass Drum and Cymbals; Tam-Tam; Harp; Banda (an off-stage group of wind and brass instruments,); Strings.

Sinfonia

Bel canto operas typically began with some kind of orchestral introduction; it could be called an “Overture” (Rossini’s favored title); or a “Preludio.” Bellini calls his a “Sinfoni,”, which implies it’s not a pot-pourri of the melodies we are destined to hear during the next few hours. It is, though, a musical introduction to what we will see on stage: the ever-belligerent Druids longing to rid themselves of the hated Roman occupiers, yet tamed by their religious devotion to their High Priestess; and the great human love between the three main characters.

Act 1 – Oroveso and Druids

It is night when the curtain rises. We are in the woods sacred to the Druids; Irminsul’s sacred oak tree, with his altar stone at the base, is center-stage. Over rolling timpani, horns – and then bassoons – quietly suggest we should prepare ourselves for a march; violas and cellos contradict that notion and the bassoons soon agree with them, though they drop out to listen to the cellos finish the phrase. Winds and violins (playing in their lowest register) repeat the solemn melody and then hold us in suspense for a few bars before the piccolo and clarinet, playing softly, give us the promised march. “A march played softly?”, I hear you ask; but remember this music accompanies a religious procession, not a military one, and the Druids, surrounded by their Roman oppressors, need to move quietly. The huge, very martial, explosion from the full orchestra probably represents the frustrations the Druids feel; it quickly calms down to allow us to hear Oroveso, the Arch Druid, tell the men to watch from the hills for the first sign of the new moon and to strike the sacred gong when they see it rise.

I hate to divert your attention away from what a character is telling us, but listen here to the orchestra: it’s playing a shortened recapitulation of the introduction, which is unusual. “Will Norma come to cut the sacred mistletoe” the Druids ask, and the full orchestra, with great fanfare, supports Oroveso’s “Yes!” Finally we get the military march Bellini has withheld from us! The chorus begs Irminsul to inspire Norma with their hatred of the Romans so that she will break the peace treaty. Oroveso tells them that Irminsul will speak from the ancient forest and will free the land of the Romans. Echoing the transition at the end of the Sinfonia, the scene ends with a re-recapitulation by the entire wind section of the opening while the Druids, now off-stage, beg the moon to quickly rise and for Norma to come to the altar.

Here’s food for thought as we are where we are in our discussion of Norma. Bellini’s “Sinfonia” begins in the key of G minor, but moves to G major. Which is the key we’re in when the curtain rises. And the key we stay in throughout the scene. With such an insistence on the tonality of G (initially minor, but consistently major thereafter) is Bellini using tonality as a kind of (gasp!) pre-Wagnerian tonal leit-motiv? G major is the tonality of the Druids? Let’s keep that in mind as we proceed. Certainly neither Rossini nor Donizetti seemed interested in such tonal-connective niceties. The other element to consider is that return of the opening music to close the scene; we know that the first (and sometimes the last) movements of symphonies by Haydn; Mozart; and Beethoven bring back the opening ides – it’s the “recapitulation.” Is Bellini here trying for the same formal effect? Keep those variables in mind as we proceed.

Pollione

With the Druids gone, violins introduce an Ab into the G major tonality as Flavio and Pollione enter. They begin their recitative-conversation in G major. Pollione is relieved that the Druids have gone; Flavio is not so sure: Norma has warned that these woods are dangerous. “That name chills my heart,” and we hear the shivers in the strings. But she’s the mother of your children, says Flavio. Pollione admits he no longer loves Norma, and sees only an abyss in which to throw himself; fortissimo descending strings land him in Ab major. In Ab minor Flavio asks him if he loves someone else.

And, in what only music can achieve, we are transported to a different world. The Cb of Flavio’s Ab minor question is the same as the note B, which Bellini treats as the dominant of E major which the strings establish with an accented tremolo. Apologies for getting so technical, but I’m sure you’ll hear the brightness of the new key, which allows Pollione to open up to Flavio: he loves Adalgisa, a “flower of innocence” and so happy. Minor key when he says she’s a priestess in the temple of what he calls this “god of blood,” though she (with softened chords) is like a star in a troubled sky. “Does she love you?” “I am sure of it.” “Don’t you fear Norma’s anger?” Nasty chord as Pollione admits it will be terrible and that he had a dream about it.

In C major he tells us they were about to be married in Rome; wedding hymns and incense added to his intoxication with Adalgisa. All of this is sung to a beautifully smooth melody, though the second phrase’s move to A minor is a bit unsettling. The basic accompaniment is nothing unusual, but what is the wind-section doing with its triplet chattering?

The C minor tonality and the agitated triplet figures in the lower strings accompany Pollione’s telling of what happened next. Suddenly, a huge Druidic cloak enveloped Adalgisa; she disappeared, though he could still hear her, together with the voices of his children. The cellos and basses are agitated when he tells us about the frightening voice he heard. Listen to the oboes and clarinets answered by the bassoons and lowest strings insisting on a C#-D as he tells Flavio what she said: “This is how Norma takes revenge on her traitorous lover!” Off-stage the sacred gong is heard over an orchestral discord.

Fanfare, in Eb, from the banda, punctuated by the second and third strikes of the sacred gong. The march we hear (and honestly it’s a very trite tune) indicates, says Flavio, Norma’s approach to perform the sacred rite. Off-stage the Druids sing of the risen moon and warn away any unbelievers. Flavio urges Pollione to leave, but he is reluctant: “The barbarians are plotting against me, but I shall thwart their plans.” In the required faster section of his aria, he is confident that Love will protect him and he will destroy the forests of the god who would take Adalgisa from him. The Romans leave. Bellini, apparently, was not happy with the music he gave Pollione in this scene. The description of the dream is certainly not the best of Bellini, but at least it’s better than the second half of the aria, which, in turn, is better than the trite march!

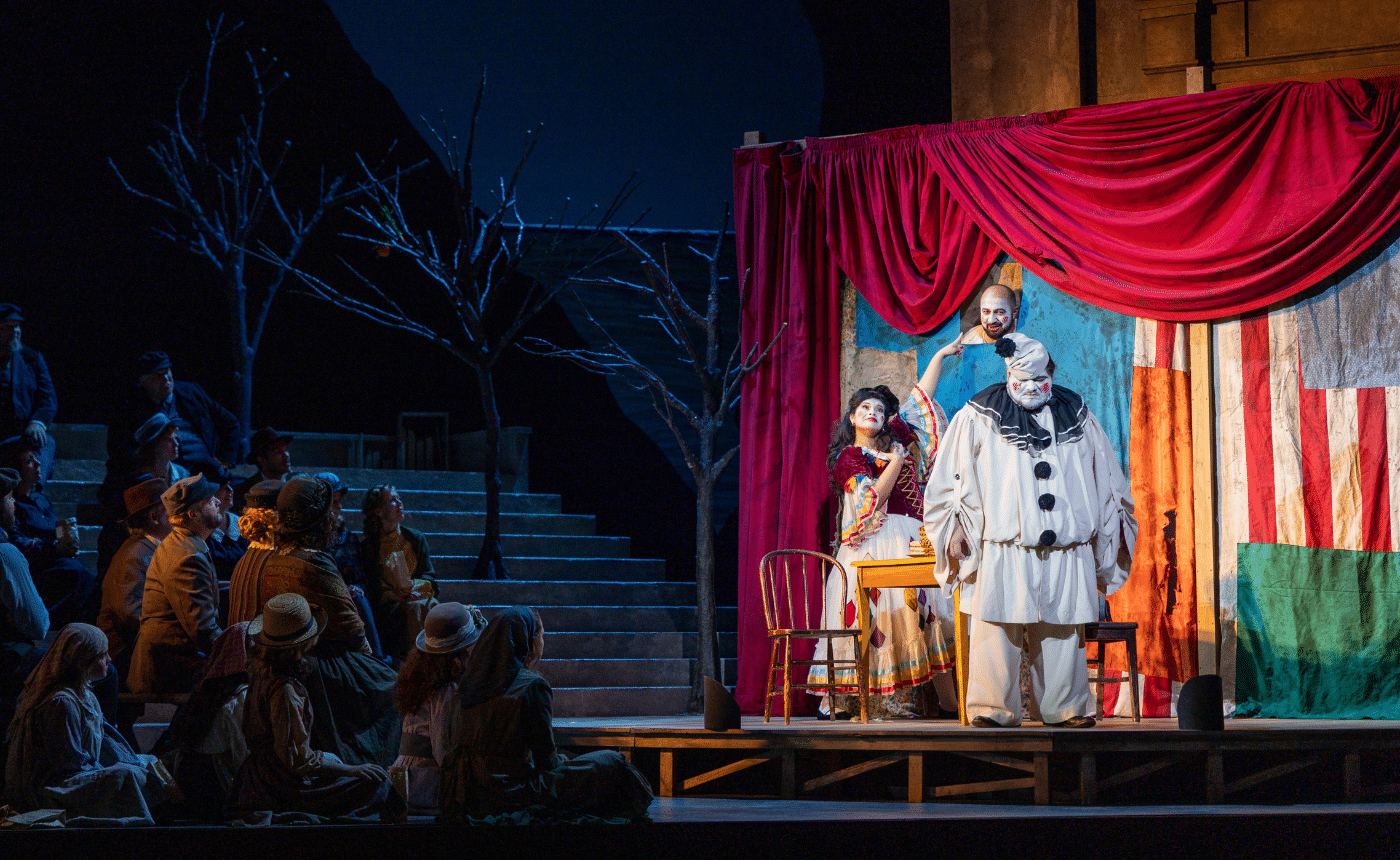

Entrance of Norma and Druid Priestesses

With massive chords, and still in Eb, the orchestra ushers in the Druids; Priestesses; Warriors; Bards; and among them is Oroveso. Suddenly the orchestra drops to very soft chords. The banda joins the orchestra for a repeat of the march we heard earlier in the scene. To solemn brass chords the chorus announces the arrival of Norma. Winds and brass repeat the opening chords; silence now separates the phrases.

Norma is angry. In a dramatic recitative she demands to know who dares to raise warlike voices near the holy altar. Thunderous chords from the orchestra. “Who dares question the inspired words of Norma, and seeks to hasten the fate of Rome? That will not happen by means of human efforts.” Oroveso demands action against the Romans: “They have oppressed us long enough. The sword of their chief, Brenna, must be used.” The Druids support that notion. That time is not yet come, replies Norma; Roman weapons are more powerful than yours. Everyone demands to know what their god has commanded her to do and what has been prophesied. “Rome will die, consumed by her own vices; we must wait for the hour decreed by god, and meanwhile, peace must be maintained. I will cut the sacred mistletoe.”

“Casta Diva”

The key of Eb and the time-signature of 4/4 have dominated the last two dozen pages of the vocal score. But as Norma cuts the mistletoe and the priestesses collect it in baskets, a huge change occurs: the tempo changes from fast to a very sustained Andante; the time signature becomes 12/8; and the key changes abruptly to F major. In the manuscript, the harmonic transition at the end of the recitative into the aria was not so abrupt because, according to Herbert Weinstock’s “Vincenzo Bellini: His Life and His Operas,” that key was G major (which, you will remember, may be Bellini’s “Druidic key”). We know that Giuditta Pasta (the composer’s favorite soprano, by the way) initially refused to sing the aria, as she felt it “ill adapted to her abilities.” Bellini suggested she sing it over every morning for a week and if she still didn’t like it he would change it. Their compromise, it seems, was to lower the key one whole step.

Over the violins’ simple arpeggiated accompaniment, a solo flute begins “one of the longest-breathed and most enchanted melodies ever conceived” (Weinstock). Norma implores the chaste goddess to look kindly on her people. The chorus repeat her words, but what extraordinary melismas Norma sings over them: it’s as if she is vocally possessed by a religious ecstasy! Breathtakingly beautiful – the perfect example of the bel in bel canto! In the second verse, with the chorus singing under her, she begs the goddess to bestow on her people her heavenly peace.

Back in Eb, the first few phrases of the march are heard from the banda. “The rite is ended. Everyone should leave the woods; when the angry god demands Roman blood, my voice will thunder forth.” “When that happens,” says the chorus, “let them all be killed, with Pollione the first one to die!” “I can punish him,” but, in an aside, “my heart could never do that.” In the second half of the aria she longs for Pollione to return to her and restore the beauty of their first love. Her coloratura passages perfectly illustrate her uneasy longing. Oroveso and the chorus beg their god to hasten the day when the Romans will be destroyed. Everyone leaves as the full orchestra plays “The Druids’ March.”

Adalgisa and Pollione

A change of key to Bb major, and we hear a heart-beat in the bassoons and low strings. First violins begin a nervous idea, while a solo flute and clarinet add a melody which, unaccompanied, would appear relatively calm, but the nervousness of the first violins gives the lie to that calmness. Adalgisa enters, relieved to find the sacred grove empty after the rite. Here she can sigh unseen by anyone. It was here, she tells us, that she first saw the Roman who made her a traitor to her god. If only that first time had been the last! She longs to see him again and hear his voice. Violins and clarinets introduce a melody which almost sounds hymn-like. Adalgisa runs to Irminsul’s altar stone and, in heartfelt phrases, begs the god to protect her; “have pity on me, for I am lost.”

Pollione and Flavio enter; seeing Adalgisa, Pollione tells his friend to leave. Two bars of decisive strings bring Pollione to her. “Were you crying? “I was praying” – Andante, and very lyrical – “leave me and let me pray.” In recitative Pollione reproaches her for praying to a cruel god, opposed to both of their desires. “You should pray to the god of Love.” “I cannot listen to you.” “You want to avoid me? Where would you go that I would not follow?” “To the sacred altar whose bride I am.” “And our love?” A high note which is to be held for a long time, with a swelling and then fading in volume (a basic element of bel canto vocal technique): “I… “, says Adalgisa, “…have forgotten it.”

The full orchestra expresses Pollione’s astonishment. Over agitated violins (Bellini felt his figuration might be too difficult for some, so he added an easier alternative) he tells her to offer his blood to her god, but he will never leave her. Flutes and clarinets calm the violins’ fury and, with oboe added, introduce a more lyrical melody (borrowed from an earlier song). “You were promised to your god, but you gave your heart to me.” Telling her she has no idea of the cost to him if she renounced her love, agitation returns, but this time in Pollione’s vocal flourishes.

On the contrary, replies Adalgisa, repeating the music, complete with the tricky violin part, of Pollione’s verse. “You don’t know the pain I’ve suffered in loving you. I was innocent and happy to be given to the altar which I have profaned.” In the more lyrical section she tells him how her thoughts rose to heaven and to god; but now, having betrayed her oath, both are forbidden her.

“There’s a purer heaven and better gods in Rome; I leave at dawn.” The news stuns Adalgisa, and her distress can be heard in the violins and brass; she begs him to speak no more, but in a phrase whose ascent expresses his rising passion (and also his frustration) he tells her he’ll go on repeating his words until she listens to him. The orchestra calms down as she prays heaven to protect her. “How can you abandon me like this, Adalgisa?”

In the relative-major key of Ab (the duet began in F minor), he tenderly (plucked strings accompanying him) pleads with her to come to Rome where they can be happy together. To herself (and to the same music), Adalgisa mourns (or maybe rejoices) that she hears his voice and sees his physical presence everywhere – even on the altar: he conquers her tears and sorrow. “Take this pleasure from me, god, or else forgive my sin.” More pleading. More hesitation. Finally, Allegro risoluto, she gives in. “I will renounce my god, but I will always be faithful to you.” “Your love encourages me, and I will defy your god.”

Norma at home

The scene changes to Norma’s house. We are in the key of A minor, a tonality we’ve not heard so far. A long orchestral introduction perfectly captures Norma’s emotional turmoil: tremendous energy (the marking is Allegro agitato) quickly followed by hesitation: the fast ending of the first phrase (1st violins and 2nd flute) is immediately echoed, more slowly, by the oboe. Silence. The sequence is repeated a step higher, and this time it’s the 1st flute which echoes. Silence. An ominous figure from the lower strings and bassoon is answered by a kind of scream from flutes and 1st violins. Strings eventually calm down, and in a slower tempo the oboe plays a broken melody accompanied by a restless figure which will return in the final scene when Norma remembers her children; so let’s call melody and accompaniment “The Children,” just as if we were labelling one of Wagner’s “Leitmotifs.”

Norma is there, with Clotilde and two little children. She tells Clotilde to hide the children as she fears to hug them. “The Children” in the strings and winds. Why she does not know; the “motif” stops, and we shift to recitative. “I love and hate my children at the same time; I hate to see them, but hate when I can’t. I feel both pain and joy in being their mother.” “You are their mother?” “If only I weren’t!” In recitative she tells her that Pollione has been recalled to Rome. “And you’ll go with him?” “He hasn’t said. But…(pause) , …(passionately) if he wanted to go…(pause) and leave me here? Could he forget his children? That’s too horrible to consider.” Strings get agitated; Norma knows that someone is outside and bids Clotilde to take the children away: she embraces them before they leave.

Norma and Adalgisa

It is Adalgisa, in Bb (the key of her entrance in the previous scene) and Andante sostenuto. Norma welcomes her over comforting strings. In recitative she says she’s heard that Adalgisa has a secret. She has, but begs Norma not to look on her so severely, and prays she may have the courage to confess everything. For a long time she has tried to conquer her love, but just now swore to betray her god and leave her country. Norma grieves that Adalgisa’s young life has been so upset, and wonders when, and how, she fell in love. “At first sight” is the reply. Norma, distratta, remembers how she, too, fell in love in the same way; her memories overlap with, and sometimes join with the solo flute, in F minor, announcing the melody of Adalgisa’s confession. To her telling of their initial meeting and their growing love Norma, aside, notes the parallels with her own seduction by Pollione; and even closes out the final phrase of Adalgisa’s verse. The second verse changes when Adalgisa begs for forgiveness, and asks for Norma’s help. Norma assures her she is not bound by any vow; in a faster, more excited melody, in C major, she absolves her from any promises, and hopes, with increasing vocal flourishes, that Adalgisa will live happily with the man she loves. Much relieved that her love is no crime, Adalgisa asks Norma to repeat her words, which she does, and the two ladies join in a celebration of their combined voices.

First violins continue the happiness of the duet, though the shudders from the second violins, violas and cellos might give us pause that such happiness might continue. The opening phrase ends on G, and pause we definitely should seize when that G is repeated as the third of an Eb dominant 7th chord, left hanging as a kind of cloud which quickly passes over the sun of C major. Norma wonders who the young Gaul might be; Adalgisa’s reply that he’s a Roman provokes much agitation, though softly, from the strings. Pollione enters and Adalgisa indicates that he is the one. Norma is stunned, as is the orchestra, which takes some time to settle into a tonality. Adalgisa is mystified by Norma’s reaction, though Pollione tries to comfort her.

Norma, Adalgisa, and Pollione

Furiously Norma explodes, telling Pollione he should not be afraid for Adalgisa, since she is not guilty: be afraid for yourself; for your children; and, in a final display of vocal fireworks, be afraid for me. Slowly Adalgisa understands the situation, and is horrified.

In Bb major (the key of Adalgisa’s arrival in this scene – and also the key of her first entrance in the previous one) Norma’s words seem to console Adalgisa by lamenting her cruel deception by the man who also deceived her. Certainly the Andante tempo and the melody itself seem consolatory on the surface. But Norma’s rage, not just at her betrayal by Pollione, but that he would betray her with Adalgisa, undermines her words: plucked strings may provide the “oom” but it’s the horns (more sinister) who play the “chuck-chuck”; and it’s not just the accents and the deciso direction to the clarinets who play along with the singer: it’s those gaps in the vocal line and the accented notes which show us her suppressed anger.

This is not the time for scorn, Pollione tells Norma; do not upset the already troubled Adalgisa by telling her of their earlier relationship, and don’t assign guilt for its failure on either one of them. Vocally Adalgisa seems to be aligned with Pollione, though what she says is very different: I suspect, but fear the truth; my heart will break if he has deceived me. A solo horn, in unison with shuddering 1st violins and cellos end this section.

Allegro risoluto, and though the key signature stays in Bb, the strings are in Eb; Bellini directs them to accent only the first beat of the bar. Another figure depicting Norma’s simmering rage, as she denounces him as a traitor. He wants to leave with Adalgisa, but she’s having none of it: you are an unfaithful husband. Passionately, and in a faster tempo, he tells her he has forgotten what he was, but knows that he is now her lover; I am fated to love you and forget her. Passionate outbursts can be expected from tenors, but I don’t know of many which are marked pianissimo – at least the orchestra is. Obviously his words are meant to be heard only by Adalgisa, and the syncopated 2nd violins and violas illustrate her emotions: Leave me, traitor!

Norma cuts short Pollione’s protestations. Lento the strings tremble with an ominous silence on the fourth beat. “Accept your fate and go.” Back to the faster tempo, but dropping down a half-step, Norma tells Adalgisa to go with him. “Never. I’d rather die!” That half-step drop becomes the dominant of the G minor start to the final section of this amazing trio.

Bellini asks for a very agitated fast tempo as Norma dismisses her former lover: forget you children, your vows, your honor, worthless man; but know that, cursed by me, you will never find happiness. Given Norma’s earlier expressions of her emotions, we might expect some brilliant vocal pyrotechnics here, but Bellini is too smart a (pre)psychologist for that. Her melody is contained within a relatively small range, and not until she bursts out in the tonic major does she sing beyond an octave, and then only barely. It’s the strings which give us her suppressed emotions: cellos and basses share a triplet rhythm with the violins while the violas’ first and third beats shudder in 16th notes. You pianists know how tricky it is to play two eighth-notes in the right hand against a triplet accompaniment in the left. It’s even more unsettling, in every way, if it’s four notes against three. And that’s what Bellini is doing here. Though the chances that his rhythmic subtlety will be noticed by anyone other than someone following along with the score are slim to none! Still I thought you should be aware of what is unsettling here.

Back in G minor, the accompaniment settles down to regular eighth-notes from plucked strings as Pollione and Adalgisa address Norma. He is defiant: I don’t care if you hate me; this new love is greater than either of us, and I regret the day when we met. Adalgisa regrets causing Norma such pain and vows to reunite them. Goodness! Is Bellini writing a canon here, where one voice starts the melody and a second one enters a bit later with the same melody (think “Row, row, row your boat”)? Not exactly. But by having Adalgisa begin her phrases a bar later then Pollione, Bellini is letting us hear they are already divided as a couple. In unison, and in the tonic major, they are interrupted by the off-stage chorus, together with the triple stroke of the sacred gong, calling for Norma to come to Irminsul’s altar at his express command. Pollione is all defiance, but he is warned that the voices he hears intend his death and he should leave immediately. Which he does. Act 1 ends in G major.

Another example of Bellini establishing G major as the Druidic tonality? Remember that the Sinfonia begins in G minor, and ends in G major? And that the first scene, with Oroveso and the Druids is in G major? And that Norma’s “Casta Diva” was originally in G major? And that this final trio, as well as Act 1, ends in G major. Was Bellini trying to ground the Druids (and Norma) in that tonality? Let’s see what happens in Act 2.